Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 (27 page)

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

Determined to expose the administration's folly to public scrutiny, on February 1966 Fulbright convened the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for special hearings on the war. Forever after Johnson would refer to Fulbright as“Halfbright," a nickname Harry Truman had coined for him. In an effort to upstage the hearings, Johnson convened another conference in Honolulu that met for three days beginning on February 6. There he met with Nguyen Van Thieu, Nguyen Cao Ky, Henry Cabot Lodge (who had replaced Maxwell Taylor as ambassador), Maxwell Taylor, and William Westmoreland.

The Honolulu Conference did not overshadow Fulbright's hearings. Dean Rusk testified for hours spouting the administration line about external communist aggression and saving Southeast Asia. Fulbright countered that the war had really started out as“a war of liberation from colonial rule … [which] became a civil war between the Diem government and the Vietcong… . I think it is an oversimplification … to say that this is a clear-cut aggression by North Vietnam.” Fulbright brought in James Gavin, who opposed escalation and called for the enclave strategy in place of offensive operations. Fulbright's trump card was George Kennan, the architect of the containment policy by which the Western nations had confronted communism since the late 1949s. Kennan testified that Vietnam was far away and only tangential to American strategic interests, and that the United States“should liquidate the involvement just as soon as possible.”

The hearings changed few minds. Wayne Morse pushed a bill to repeal the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, but it was voted down ninety-two to five. The Senate approved another $12 billion for the war. Westmoreland launched search-and-destroy missions in all four corps zones. More than 1,700 American troops died in the first three months of 1966, but they killed 15,000 enemy troops. Ho Chi Minh replaced each one, deploying the NVA 324B and 324C Divisions into South Vietnam. The death tolls steadily mounted in 1966, and at midyear Westmoreland asked for 100,000 more troops, hoping to have 480,000 in the field by mid-1967 and as many as 680,000 by early 1968. The joint chiefs urged Johnson to expand the Rolling Thunder raids to include petroleum storage facilities in Hanoi and Haiphong, and at the end of June 1966 he did so.

By that time the war was taking its toll within the administration. George Ball, a longtime critic, finally resigned as undersecretary of state. McGeorge Bundy, the national security adviser, decided the troop buildup had assumed ridiculous proportions. He left the White House in 1966 to head the Ford Foundation. Johnson replaced him with Walt Rostow, who still preached military victory over North Vietnam and looked to the modernization of South Vietnam. Westmoreland continued his cheery reports. But the president sensed that he was losing control of the war. One night in June 1966 he could not get to sleep. Pacing the floor and cursing, he woke up Lady Bird complaining that“victory after victory doesn't really mean victory. I can't get out. I can't finish it with what I have got. So what the hell do I do?”

7

The Mirage of Progress, 1966–1967

It lies within our grasp—the enemy’s hopes are bankrupt. With your support we will give you a success that will impact not only on South Vietnam, but on every emerging nation in the world.

—William Westmoreland, November 1967

For the first time in history a battlefield commander, in the middle of a war, was addressing a joint session of Congress. President Johnson had summoned Westmoreland home to discuss the latest requests for more ground troops. On April 28, 1967, his starched uniform tattooed with medals and ribbons from other wars, the general stood ramrod straight and begged for time and support. The greatest problem American boys faced in Vietnam was not enemy troops, he argued, but the will at home to continue: “These men believe in what they are doing. . . . Backed at home by resolve, confidence, patience, determination, and continued support, we will prevail in Vietnam over the Communist aggressor.” The thunderous applause reminded many of Douglas Macarthur’s homecoming speech with the phrase from a military song “old soldiers never die.” Pivoting in a crisp about-face, Westmoreland saluted Vice President Hubert Humphrey and Speaker of the House John McCormick, made another half-spin and saluted the entire Congress, and then marched out of the House. It was great theater, “a good speech” even in the judgment of Senator J. William Fulbright. “From the military standpoint it was fine,” he said. “The point is the policy that put our boys over there.”

Whatever Westmoreland was saying publicly, his private comments had frightened people at the White House. In response to a question from Robert McNamara about how long it would take to achieve victory, Westmoreland said that it could be five years. The enemy was far more determined than anyone had anticipated.

At the end of October 1966 Johnson, as always thrashing about trying to find some way of explaining the war to himself and the world, had flown to Manila to meet with American military officials and the heads of state of South Vietnam, Australia, Thailand, South Korea, and the Philippines. At the end of the conference he issued the Manila Declaration calling for peace in Southeast Asia and cooperative efforts to conquer hunger, disease, and illiteracy, and provide freedom and security for everyone. On an impulse, he flew from the Philippines to the huge American base at Cam Ranh Bay, South Vietnam, where he waded into GIs shaking hands as if it were an election for county commissioner. The troops received him with so much enthusiasm that Johnson renewed his dedication to the war. He urged the GIs to keep fighting until they “nailed the coonskin to the wall.” But Johnson really did not want to continue the hunt. Throughout 1966 he sent prominent American diplomats around the world with the message that he was ready to discuss “any proposals—four points or fourteen or forty; we will work for a cease-fire now or once discussions have begun.” Yet Ho Chi Minh’s position had not changed: End the bombing, withdraw American troops, remove Thieu and Ky from office, and establish a coalition government in South Vietnam that included the National Liberation Front. “I keep trying to get Ho to the negotiating table,” the president remarked to Dean Rusk. “I try writing him, calling him, going through the Russians and the Chinese, and all I hear back is 'Fuck you, Lyndon.'” Of course Johnson’s diplomatic posture had not changed either. The United States still insisted that first North Vietnam withdraw its troops from the South and stop supplying the Vietcong. Nor was Johnson willing to accept any political role for the National Liberation Front in South Vietnam. Vice President Hubert Humphrey said it “would be like putting the fox in the chicken coop.” All the mediation attempts failed.

Perhaps, in time, American bombs would break the impasse. The Jason Study, commissioned by Robert McNamara in 1966, initially confirmed the effectiveness of the bombing campaigns, which encouraged administration officials in their conviction that airpower could bludgeon North Vietnam into submission. But the air war increasingly revealed itself to be a disaster.

The most stunning failure was in the bombing campaigns over the Ho Chi Minh Trail. They had little or no success in cutting off the Vietcong and North Vietnamese troops from their supply bases above the seventeenth parallel. The communists were constantly improving the transportation system into South Vietnam. In 1963 the Trail had been primitive, requiring a physically demanding, month-long march of eight-een-hour days to reach the south. But by the spring of 1964, the North Vietnamese began striking improvements in the trail. They put nearly 500,000 peasants to work full and part time, building and repairing roads. In one year the communists built hundreds of miles of all-weather roads complete with underground fuel storage tanks, hospitals, and supply warehouses. They built ten separate roads for every main transportation route. By the time the war ended, the Ho Chi Minh Trail had 12,500 miles of excellent roads, complete with pontoon bridges that could be removed by day and reinstalled at night and miles of bamboo trellises covering the roads and hiding the trucks. As early as mid-1965 the North Vietnamese could move 5,000 men and 400 tons of supplies into South Vietnam every month. Robert McNamara estimated that by mid-1967 more than 12,000 trucks were winding their way up and down the trail. By 1974 the North Vietnamese would even manage to build 3,125 miles of fuel pipelines down the trail to keep their army functioning in South Vietnam. Three of the pipelines came all the way out of Laos and deep into South Vietnam without being detected.

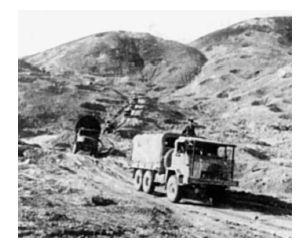

A truck convoy rolls along a road into Laos and the Ho Chi Minh Trail as it transports supplies to North Vietnamese troops fighting in South Vietnam.

(Courtesy, National Archives.)

Nor did the bombing campaigns do any militarily significant damage to North Vietnam itself. The country had an agricultural economy with few industries vital to the war effort. Anticipating an escalation of the bombing, the North Vietnamese had built enough underground tanks and dispersed them widely enough to have a survival level of gasoline, diesel fuel, and oil lubricants. In 1965 and 1966 North Vietnam began evacuating nonessential people from cities and relocating industries— machine shops, textile mills, and other businesses—to the mountains, jungles, and caves. Home manufacturing filled the modest need for consumer goods. By late 1967 Hanoi’s population had dropped from one million to 250,000 people. A little planning robbed the American pilots of their effectiveness. The only targets that could not be moved were bridges, roads, and transportation centers, and almost as soon as they were bombed the North Vietnamese repaired them. They replaced steel bridges with ferries and easily mended pontoon bridges. A long history of fighting the drought and flooding in the Red River Valley was sustaining a cooperative spirit among the North Vietnamese. Political teams organized people to repair roads, help troops and supplies get across rivers, and build air-raid shelters, bunkers, tunnels, and trenches. American pilots were returning to the same places again and again to bomb the same targets. And while the bombing campaigns over North Vietnam eventually killed as many as two million people there, the effect of the air war was to stiffen the will of the North Vietnamese, deepen their resentment of the United States, and cement the power of the communist leadership. George Ball’s conclusions about the limits of allied strategic bombing in Germany and Japan, and his suspicions about what a similar campaign would achieve in Vietnam, had proven disturbingly accurate.

The bombing was, to be sure, devastating. During the war the United States dropped one million tons of explosives on North Vietnam and 1.5 million tons on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In 1967 the bombing raids killed or wounded 2,800 people in North Vietnam each month. The bombers destroyed every industrial, transportation, and communications facility built in North Vietnam since 1954, badly damaged three major cities and twelve provincial capitals, reduced agricultural output, and set the economy back a decade. Malnutrition was widespread in North Vietnam in 1967. But because North Vietnam was overwhelmingly agricultural—and subsistence agriculture at that—the bombing did not have the crushing economic effects it would have had on a centralized, industrial economy. The Soviet Union and China, moreover, gave North Vietnam a blank check, willingly replacing whatever the United States bombers had destroyed.

Weather and problems of distance also limited the air war. In 1967 the United States could keep about 300 aircraft over North Vietnam or Laos for thirty minutes or so each day. But torrential rains, thick cloud cover, and heavy fogs hampered the bombing. Trucks from North Vietnam could move when the aircraft from the carriers in the South China Sea could not.

Throughout the war the North Vietnamese steadily improved their air defense system until it was the most elaborate in the history of the world. They built 200 Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missile sites, trained pilots to fly MiG-17s and MiG-21s, deployed 7,000 antiaircraft batteries, and distributed automatic and semiautomatic weapons to millions of people with instructions to shoot at American aircraft. The North Vietnamese air defense system hampered the air war in three ways. American pilots had to fly at higher altitudes, and that reduced their accuracy. They were busy dodging missiles, which consumed the moment they had to spend over their target and reduced the effectiveness of each sortie. And they had to spend much of their time firing at missile installations and antiaircraft guns instead of supply lines.

The full recognition of the futility of the bombing would come later in the war. In 1966, Dean Rusk and Walt Rostow had the Jason report to encourage them. The answer must be more bombing. Until May 1965, American bombing raids had been confined to targets south of the twentieth parallel. After May Johnson lifted several restrictions, though he still ordered American pilots to hit no targets within thirty miles of Hanoi or the Chinese border or within ten miles of Haiphong. In April 1966 the operational area was expanded to all of North Vietnam, and by the end of June the list of targets included petroleum storage facilities in Hanoi and Haiphong. Rolling Thunder attacks expanded in February 1967 to include factories, railroad yards, power plants, and airfields in the Hanoi area. From 25,000 sorties over North Vietnam in 1965 the number increased to 79,000 in 1966 and 108,000 in 1967. The United States stayed with the bombing campaign because it was cheaper, in dollars and lives, than ground combat and therefore more acceptable at home.

Robert McNamara was ready to try another technological tool. The only sure way of stopping infiltration across the Demilitarized Zone from North Vietnam was to station huge numbers of troops just south of the seventeenth parallel. Instead, McNamara proposed construction of an electronic barrier. Critics dubbed it “McNamara’s Wall.” The Third Marine Division agreed to construct the barrier—a twenty-five-mile bulldozed strip of jungle complete with acoustic sensors, land mines, infrared intrusion detectors, booby traps, and electronic wires along the northern border of South Vietnam to detect NVA infiltration. The marines constructed a bulldozed strip of land 660 yards wide and 8.2 miles long from Con Thien to the sea, but the project was weighed down by its own overambitious technology, besides lacking sufficient support from the military. The whole idea struck the North Vietnamese as silly. “What is the use of barbed wire fences and electronic barriers,” said General Tran Do, “when we can penetrate even Tan Son Nhut air base outside Saigon?”

It was that kind of war. For most American combat soldiers, the Vietnam experience combined surrealistic incongruity, boredom, suffering, and danger.

At the beginning of the buildup in 1965 and early 1966, most troops arrived in South Vietnam by ship after long voyages from the United States. Their journey to war was not unlike that of their fathers, who had gone to Europe and the Pacific in large, crowded troop transports. By the end of 1966, however, most of the major military units had deployed to Vietnam, and replacement troops arrived by commercial jet. With more than one million American soldiers arriving or leaving the country each year, the military did not possess enough planes or ships to carry the load, so they contracted the job out to commercial airlines. Soldiers went to war in air-conditioned jets, drinking cocktails and beer along the way and ogling the short-skirted stewardesses. Recalling his own trip to South Vietnam via Braniff Airlines, Rob Riggan writes in

Free Fire Zone:

“We might have been over Gary, Indiana. . . . Stewardesses with polished legs and miniskirts took our pillows away from us. As we trooped out the door, they said: ‘Good luck! See you in 365 days.’”