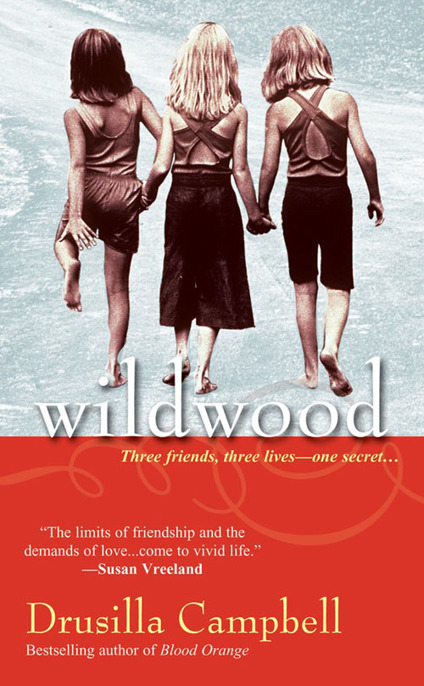

Wildwood

Authors: Drusilla Campbell

Also by Drusilla Campbell:

Blood Orange

The Edge of the Sky

Wildwood

Drusilla Campbell

KENSINGTON BOOKS

http:/www.kensingtonbooks.com

http:/www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For AWC, PLC, and the RBR

Acknowledgments

A number of people have read all or parts of

Wildwood

through its various incarnations. At the beginning there were Marion Jones and Peggy Lang; at the end I counted on Judy Reeves and Susan Belasco Hayhurst and my editor, Ann LaFarge, for their insights and opinions. The Women of Arrowhead supported and sustained me as did Art Campbell. If he ever got tired of talking about

Wildwood

and its characters, he kept it to himself. A special thanks to my sons, Matt and Rocky, who believed in me and kept the computer running. And to my agent, Elly Sidel, for her honesty, determination and friendship.

Wildwood

through its various incarnations. At the beginning there were Marion Jones and Peggy Lang; at the end I counted on Judy Reeves and Susan Belasco Hayhurst and my editor, Ann LaFarge, for their insights and opinions. The Women of Arrowhead supported and sustained me as did Art Campbell. If he ever got tired of talking about

Wildwood

and its characters, he kept it to himself. A special thanks to my sons, Matt and Rocky, who believed in me and kept the computer running. And to my agent, Elly Sidel, for her honesty, determination and friendship.

I am grateful to Dr. Robert Slotkin, Dr. Chris Khoury, and Dr. Dale Mitchell and his nurse, Adele, each of whom patiently answered my questions about the physiology and possibilities of midlife pregnancy, the emotional effects of abortion, and the varieties of Post-Traumatic Shock Syndrome.

Though

Wildwood

is entirely fictional in both its story and characters, Betty Balch, Judy Hanshue, and Jill Derby will recognize bits and pieces of our shared childhood within its pages. Bluegang Creek no longer exists. The city’s fathers and mothers and the state of California covered it with concrete and asphalt decades ago, but generations of Los Gatos boys and girls remember its pristine beauty and the summer days spent sunning and swimming and growing up on its rocky banks.

Wildwood

is entirely fictional in both its story and characters, Betty Balch, Judy Hanshue, and Jill Derby will recognize bits and pieces of our shared childhood within its pages. Bluegang Creek no longer exists. The city’s fathers and mothers and the state of California covered it with concrete and asphalt decades ago, but generations of Los Gatos boys and girls remember its pristine beauty and the summer days spent sunning and swimming and growing up on its rocky banks.

Summer

T

hat week no new polio cases were reported in Rinconada so most kids swam at the town pool. For practically the first time all summer, Bluegang Creek belonged to the birds and the squirrels and the crawdad—and a twelve-year-old girl sunbathing on a flat rock with her old Brownie shirt tied at her midriff like Debra Paget, painting her toenails with Tangee Strawberry Sundae polish, waiting for her two best friends.

hat week no new polio cases were reported in Rinconada so most kids swam at the town pool. For practically the first time all summer, Bluegang Creek belonged to the birds and the squirrels and the crawdad—and a twelve-year-old girl sunbathing on a flat rock with her old Brownie shirt tied at her midriff like Debra Paget, painting her toenails with Tangee Strawberry Sundae polish, waiting for her two best friends.

Hannah Whittaker twisted the top off the polish and took a deep breath. Strawberry Sundae smelled forbidden, grown-up and cheap—like ankle bracelets and pierced ears and the music she listened to on that Oakland radio station. The show was called

Sepia Serenade

and she didn’t know what

sepia

meant until she looked it up. Brown. Hannah Whittaker, the Episcopal minister’s daughter, closed her bedroom door and listened to Negro music down low so her parents wouldn’t hear.

Sepia Serenade

and she didn’t know what

sepia

meant until she looked it up. Brown. Hannah Whittaker, the Episcopal minister’s daughter, closed her bedroom door and listened to Negro music down low so her parents wouldn’t hear.

She steadied her right foot, lifted the brush from the polish, let it drip, then brought it gingerly over to her big toenail and painted a perfect stripe of pink. Toes were easier than fingernails. Of course it didn’t matter if she did a good job or not since she had to pick it all off before she went home. If her mother saw her painted toes, she’d catch it.

Hannah had always understood that she and her mother were not alike. This made her feel bad because if a girl wasn’t like her mother, who

was

she like? She wanted her mother to love and admire her but there seemed no way this could happen unless she made herself into someone she was not, a carbon copy of her mother.

was

she like? She wanted her mother to love and admire her but there seemed no way this could happen unless she made herself into someone she was not, a carbon copy of her mother.

Hannah had explained this to her friends, Liz and Jeanne, and they knew exactly what she meant. Sometimes she felt like they lived right inside her head and if they were captured by Communists and tortured and their tongues cut out they would still be able to communicate. That was what it meant to be best friends.

Hannah’s mom thought they all spent too much time together. She didn’t approve of the way Liz was being brought up, half neglected. She said intellectuals had “no business” having children. She wouldn’t even say what she thought of Jeanne’s parents. Just rolled her eyes. Hannah’s mother divided her world into two columns, those people who met her standards and those who did not. Women and girls were always either ladies or not. Ladies did not paint their toenails except with clear polish and where was the fun in that?

Fortunately, Hannah’s mother was easy to fool.

Hannah had headed down to Bluegang right after breakfast when Liz called and said she had the new copy of

Secrets,

snitched from Green’s Drugstore. It wasn’t like they wanted to steal; they had to. In a town like Rinconada they couldn’t even pay a quarter for a confession magazine without word getting back to someone’s mother.

Secrets,

snitched from Green’s Drugstore. It wasn’t like they wanted to steal; they had to. In a town like Rinconada they couldn’t even pay a quarter for a confession magazine without word getting back to someone’s mother.

Hannah hummed a few bars of a song she liked, “Bebop Wino.” She loved the beat and the smoky sound of the music on

Sepia Serenade,

but most of all the words which, even when they didn’t say anything, implied so much. “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” “Money Honey.” “Sixty-Minute Man.”

Sepia Serenade,

but most of all the words which, even when they didn’t say anything, implied so much. “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” “Money Honey.” “Sixty-Minute Man.”

Dirty songs, songs about sex, the dark side of the moon.

If nail polish was cheap, confession magazines were unadulterated trash. Hannah wasn’t sure what her mother meant when she said

unadulterated;

it was one of her favorite words and bad for sure.

I Married My Brother. Forced to Love—Forced to Pay. My Secret Shame.

The stories were never as good as the titles, which sent little ripples of expectant heat through Hannah’s stomach.

unadulterated;

it was one of her favorite words and bad for sure.

I Married My Brother. Forced to Love—Forced to Pay. My Secret Shame.

The stories were never as good as the titles, which sent little ripples of expectant heat through Hannah’s stomach.

Liz always kept the magazines because her mother never investigated her bedroom the way Hannah’s did. Hannah stole nail polish and lipstick from Woolworth’s and hid them in her bookcase behind boring old Nancy Drew, and she had to remember to carry them to school with her on Tuesdays because that was the day her mother dragged out the Hoover and all its attachments, the furniture polish, the vinegar and ammonia and the basket of rags and cleaned house like she expected a visit from an angel. Jeanne mixed cocktails when they slept over at her house. Last weekend they’d tried out Manhattans, which tasted the way Tangee nail polish smelled.

Hannah heard the crunch and rustle of deep oak leaves, the snap of a branch and looked up, expecting her friends. Instead she saw Billy Phillips on the hillside above her, standing on a saddle of roots from the big oak that had been undercut by high water some winters before.

“Hubba-hubba,” he said.

Billy and his mother lived next door to Hannah and went to her father’s church. Hannah’s father said Mrs. Phillips wanted Billy to be an acolyte but the ritual was too challenging for him. He was a tall, heavyset boy who should have been in high school but had been held back. He wore his hair slicked with grease like a pachuco, but he was white and Episcopalian like Hannah. With his chewed-down fingernails he picked at the clusters of white-capped pimples on his chin and forehead.

“Your girlfriends ain’t comin’,” he said. “I seen ’em up by the flume.”

“You lie.”

Billy grinned. Without a shirt on, his pale torso looked soft and feminine. She tried not to stare at his pointy pink nipples. He looked more like a girl than she did.

“Pool’s open,” he said. “How come you didn’t go? I seen you there another time. You swim good.”

She shrugged.

“That friend of yours, the one with the braces? She’s a good diver.”

“She took lessons.”

“I could dive from here.” Billy teetered on the edge of the root saddle, giggling.

“You better be careful.”

He made a face.

She caught the Tangee bottle in her fist and slipped it into the World War II khaki pack that held lunch.

“Whatcha got?”

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, oatmeal cookies and bananas, but it wasn’t Billy Phillips’s business.

“How long ago did you see ’em?” she asked.

“Couple hours.”

“Now I know you’re lying, Billy. We were just talking on the phone then.”

Billy patted the pocket of his blue jeans. “I got something.”

She rolled her eyes.

“Betcha can’t guess what.”

“Betcha I don’t care,” she said. “Whatever it is, you probably stole it.”

“Takes one to know one.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Mrs. Watson at Green’s Drug told my ma you and your girlfriends’ll probably end up in San Quentin the way you snitch stuff.”

“She never.”

He laughed.

“Shut up, Billy. You don’t even know what you’re talking about.”

“Don’t you want to know what I got?”

Hannah said, sarcastically, “I could not care less.”

“What if I said it was something of yours.”

“You’d be lying.”

“What if I said it was outa your bedroom.”

“You’ve never even been upstairs at my house.”

His laugh sounded like he was gagging for air.

She stood up. “You can just show me what it is or you can leave, Billy Phillips. You’re not even supposed to be down here.”

“It’s a free country. Who says I ain’t supposed to be down here?”

Hannah had heard her mother say if Mrs. Phillips was smart she’d never let Billy out of her sight. “Are you sure they were going to the flume?”

“That fat one—”

“She is not fat!”

“The one with hair like Nancy in the comics. She had smokes in her pocket.”

“You make me sick the way you lie.”

Billy looked up into the branches of the oak. “I bet if I was to climb up there, I could jump clear out to where the water’s deep.”

Hannah buckled her brown leather sandals and gathered up the army pack, slinging it over her shoulder. “You do that and then write me a letter. I’ll try to remember to read it.” She leaped across the space between her rock and the shore and scrambled up the path.

“Where you going?”

“Crazy,” Hannah said. “Wanna come along?”

He grabbed her arm.

“Get your cooties off me!”

He squeezed her wrist so her bones hurt.

“I’m gonna tell.”

“Yeah? Well, I could tell your ma some things about you and your girlfriends.”

“You better let me go, Billy.” Hannah wanted to ask him what he knew but more than that, she wanted to get away from him. Their raised voices had attracted the attention of the crows. A pair scolded them from the branch of a sycamore across the creek.

“I seen you down here actin’ like movie stars with your shirts tied up around your chi-chis.”

He grabbed at the Debra Paget front of her shirt and yanked it undone. With her free hand, she tried to hold it together. In her ears, a ringing began like the song of the cicadas.

“You’re in big trouble now,” Hannah said, tugging away from him. “I’ll tell my father.”

He grabbed for her again; and she kicked his shin and told herself not to be frightened—it was only dumb old Billy Phillips—but panic nipped at her anyway. She kicked again, but he was ready for her and stepped back so she lost her balance and would have fallen if he hadn’t caught her wrist again.

“I seen you plenty of times down here when you didn’t know I was lookin’.”

“You can go to jail for that. That’s spying.” She snarled the worst thing she could think of. “Commie.”

“Look in my pocket. Go ahead. I dare you.”

Her fingers were numb and tingled.

“You’re hurting me.”

“Put your hand in there,” he said.

“I don’t want to.” She began to cry.

Billy snorted. He shook her hard by the arm and she hiccupped. “Put your hand in.”

Her fingers touched the frayed edge of his denim pants pocket.

“What you think you’re gonna feel? Mr. Pinky?”

“Shut your nasty mouth, Billy.”

“You want me to let you go, you gotta . . .” Hannah squeezed her eyes shut and put her fingers into his pants pocket up to the middle knuckle. She felt something silky.

“Go on.”

“My underpants!”

It was one of her Seven Days of the Week panties. Her mother had printed her name on the elastic band with a laundry marker when she went on the day camp overnight. She thought of her mother, hanging out the wash and talking to Mrs. Phillips over the fence, thought of Billy’s hands on her shirts and shorts and underpants. She didn’t think, she just shoved the panties back at him.

“You stole these off the line, you dirty creep. I’ll tell your mother. You’re gonna get in so much trouble—”

His hand clamped over her mouth. “Wanna see Mr. Pinky spit up?”

She bit his palm. Surprised, he jerked his hand back. Her first scream rang through the woods.

Up in the field by the old chicken coop, Jeanne and Liz stopped walking. Liz was plump with her dark hair cut in a Dutch-boy style. Jeanne, a full head taller, chewed on a pigtail and talked through a mouthful of braces.

“That was a scream.” Jeanne’s S’s whistled.

Another scream, like diesel brakes on the long, snaky grade down from the summit; and a murder of crows burst from the canopy, cawing.

“That was Hannah,” Liz said.

“Come on,” Jeanne cried and ran into the trees at the edge of the ravine; and after a moment, Liz followed, slipping and sliding sideways down a steep trail through scrub oak and manzanita and thickets of pungent bay and eucalyptus trees.

A third scream ripped through the wildwood and then another, deeper.

Jeanne yelled, “We’re coming, we’re coming!”

At the bottom of the hill they found Hannah in tears, her shirt half open and filthy, leaning against the trunk of an oak tree. She looked at them accusingly.

“He said you guys went to the flume.”

Other books

The Gatecrasher by Sophie Kinsella

Beta’s Challenge by Mildred Trent and Sandra Mitchell

In Defense of the Queen by Michelle Diener

Wild Ginger by Anchee Min

Evil Dreams by John Tigges

Christian Nation by Frederic C. Rich

[06] Slade by Teresa Gabelman

The Omega Team: The Lion (Kindle Worlds Novella) by Cerise Deland

Passionate Sage by Joseph J. Ellis

To Seduce an Omega by Kryssie Fortune