Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos (4 page)

Read Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos Online

Authors: Christine Halsall

In 1938, with war on the horizon, a brash unconventional Australian named Sidney Cotton was recruited by the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) to pioneer new methods of reconnaissance to investigate the build-up of German armaments. Cotton had First World War flying experience and had spent the interwar years in various entrepreneurial activities such as seal spotting in Newfoundland, setting up aerial survey companies in Canada and buying up a controlling interest in a colour film company. In the course of promoting the latter business, Cotton frequently flew to Germany and was on good terms with influential Nazi officials. Having agreed to the spying plan, he bought a fast aircraft and fitted hidden cameras in the fuselage that could be activated at the press of a button to take clandestine photographs. Throughout the months leading up to the outbreak of war Cotton flew to and from Germany on so-called business trips, taking secret photographs of military installations, airfields and naval bases. He flew the last civilian aircraft out of Berlin only a few days before war was declared, and despite being warned not to divert from his route, managed to get photographs of the German fleet on his flight home. In a few short months he, and the experienced pilots who had joined his daring enterprise, had provided invaluable information on German military forces.

‘Cotton’s Club’, as he liked to call it, was based in a hangar tucked into one corner of Heston Airfield, a civilian airport for British Airways Ltd, west of London. Shortly after the declaration of war, the RAF took over Cotton’s Heston flight and he was commissioned as an acting wing commander to be its commanding officer. He had proved conclusively that if reconnaissance pilots were to be effective in taking the required photographs and out-fly enemy planes, their aircraft had to fly fast, fly high, be highly manoeuvrable and merge into a blue-grey background. Cotton managed to acquire Spitfire aircraft that were just coming into service; they were ideal for reconnaissance purposes after certain modifications had been made. All the unnecessary items of armour, ammunition and radios were stripped out and cameras were fitted into the space created. Extra fuel tanks were fitted in the wings to increase the aircraft’s range and the overall reduction in the weight of the aircraft made it more manoeuvrable. An application of blue-green ‘Camotint’ paint helped the aircraft merge into the colour of the sky. Reconnaissance pilots flew alone in the extreme cold for long distances; they were unarmed and navigated by dead reckoning and in radio silence. To escape from enemy fighter planes and anti-aircraft fire the pilots relied on the supreme manoeuvrability of the Spitfire and its operating height of up to 33,000ft, plus their own flying experience and skill.

Flight Officer Ursula Powys-Lybbe was head of the Airfields Section at RAF Medmenham.

Heston Aerodrome, West London, in 1939, where Sidney Cotton’s planes were based.

A reconnaissance Spitfire of 16 Squadron, 1944.

There was another urgent problem to solve. Having photographed the enemy targets successfully, the PR pilots returned to base, the photographs were processed and then … what? The almost complete absence of PI training in the interwar years had resulted in just one experienced RAF interpreter and a handful of photo-readers being in post at the Air Ministry in the summer of 1939. Photographs waited at least several days to be analysed, which was useless when enemy movements were changing by the hour. Cotton tackled this problem in his usual maverick way. Bypassing the official service route, he contacted an old friend from his days in Canada, Major Hemming, who owned a civilian aerial survey company called the Aircraft Operating Company (AOC) in Wembley, north-west London. The AOC produced detailed reports for geological and survey companies using aerial photographs and the most up-to-date measuring machines available, manufactured in Switzerland. One machine, the Wild A-5, was capable of maximising information on the small-scale photography that Spitfires had taken at high altitudes. The Wild operators readily adapted to interpreting military targets instead of commercial subjects and, most importantly, their reports were delivered to the relevant HQs within hours of a photographic flying sortie rather than days.

A three-phase system of interpretation was set up at Wembley to ensure the timely analysis of photographs and delivery of reports. First-Phase interpretation was a selective analysis of top-priority photographs carried out by the PIs who worked at the airfield from which the aircraft had flown. The process was normally completed in less than 2 hours and could trigger an immediate tactical response; on occasion the decision whether or not to launch an attack rested solely on the PI report.

Second-Phase interpretation examined all the photographic sorties flown in northern Europe in a day and then issued twice daily up-to-date reports on every aspect of enemy activity. Any photograph that raised a query was passed on to the Third-Phase specialist sections, which were concerned with longer-term strategic analysis. The three-phase system was simple in concept but extremely effective in practice, ensuring that reports on enemy activity were issued to the relevant HQs according to their level of priority, in the most efficient and timely way. The system transferred successfully to RAF Medmenham, was replicated in all the overseas reconnaissance and interpretation units, and was adopted by the Americans when they entered the war.

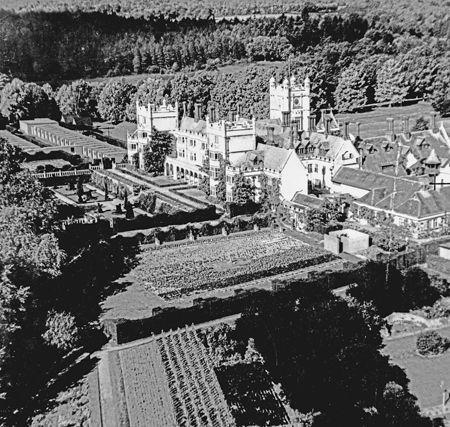

The Aircraft Operating Company in Wembley, North London, with sandbag protection in 1939.

In a matter of months Sidney Cotton had revolutionised the principles of photographic reconnaissance and engineered the changes in the organisation of photographic interpretation. He was also instrumental in pioneering the employment of women as interpreters; a highly skilled, responsible job, very different from the clerical and domestic roles women had been confined to in the First World War. The attributes of patience, attention to detail and persistence, which Cotton considered women to possess naturally, made them highly suitable for PI work. In the months leading up to war, his girlfriend, Pat Martin, accompanied him on his secret flying exploits over Germany to get photographs of military installations; she was taken because she was a good photographer, not because she was a woman. Cotton records his spying flight on 27 August 1939, just five days before Hitler invaded Poland, over German-held islands with a co-pilot and Pat operating a Leica camera with instructions to look out for fighter patrols: ‘I had hardly spoken when she tapped my arm and pointed out of her window. There, not 300 yards ahead and to starboard, flying on an opposite course, was a German fighter.’ Cotton put their escape down to the ‘Camotint’ paint.

8

By the middle of 1940 WAAF officers were being posted in to work as PIs at Wembley – the earliest date that WAAF regulations at that time would allow. Mollie Thompson was one of these officers. In 2009 she wrote:

I do not remember any tinge of ‘the old boy network’ or ‘the glass ceiling’ at Wembley or Medmenham. As far as the interpreters were concerned you did your job, you were capable and whether you were a man or a woman did not matter.

9

This opinion was echoed by many of the women concerned: the most competent person to do a particular job got it on merit – regardless of gender.

The RAF took over the Heston Flight and the AOC at Wembley in January 1940. For the first fifteen months or so of the war, reconnaissance flights were flown from Heston and the air photographs obtained were interpreted at Wembley. Heston Airfield was bombed with high explosives and incendiaries on an almost nightly basis throughout the summer of 1940 and, although Wembley suffered less, its work was regularly disrupted by bombing and the consequent damage to buildings. The increasing numbers of male and female personnel put space at a premium on both sites and larger premises were urgently sought.

At the end of 1940, the Heston unit moved to RAF Benson in Oxfordshire and was renamed No. 1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (1 PRU), remaining there for the rest of the war. Several senior PIs from Wembley set about finding a new, suitable home for photographic interpretation. The requirement was a property large enough to house the growing numbers of PIs and their equipment, conveniently close to RAF Benson and to High Wycombe, where HQ Bomber Command was sited. They found what they were looking for in a Thameside village in the Chiltern Hills.

Medmenham – we have the Anglo Saxons to thank for the tongue-twisting name of the village, meaning followers of the Saxon leader Meda. Even today it is a small village standing on a wooded road 3 miles equidistant from Henley-on-Thames and Marlow. A string of houses and some old timber-framed cottages line the lane that leads down to a slipway on to the River Thames, where once there was a chain ferry. The population totalled less than 1,000 in the 2001 census; it was probably larger in 1086 when the value of its lands and livestock were sufficient to be recorded in Domesday Book. Seven centuries after that, the ruins of its Norman abbey achieved national notoriety as the location for Sir Francis Dashwood’s infamous Hell Fire Club. The other Norman building, St Peter’s church, still stands beside the Henley road with the sixteenth-century Dog and Badger Inn opposite.