Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos (8 page)

Read Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos Online

Authors: Christine Halsall

When, within a few weeks I became corporal in charge of them, I watched them, listened to them, helped them write their letters home, bullied them to bed when they came in drunk, forced them to wash and mend their underwear, man-handled them apart when they indulged in hair-tearing, clawing quarrels and discovered some nine months later, when I was posted to be commissioned as an officer, that I loved them. They were sad, one or two shed tears and the oldest of them, a woman of nearly forty, summed up their thoughts when she sighed and said: ‘Well, we’re not surprised.’ I had never known so much raw, rumbustious, uninhibited life.

15

Although WAAF personnel were in the majority at Medmenham, a few WRNS officers and a number of ATS officers and NCOs also served there. In 1939 Joan ‘Panda’ Carter had a job in the Admiralty Drawing Office, and, after being called up into the ATS, was sent to Talavera Camp in Northampton for basic training. Of the twenty-four recruits in her hut:

Two had their heads shaved because of lice, one wet the bed nightly and another had regular nightmares and walked in her sleep. Our four weeks training was like a complete new world. Each day, come rain, shine or snow, when the camp was ship-shape, we spent many hours learning how to march and obey commands. I enjoyed it after a while, and even knew my left from my right. Our uniforms fitted smartly and we were medically A1, having had all the appropriate injections.

The last part of our training consisted of a variety of tests to decide for what kind of work we were most suited. It was like being back at school. We had to sit several written papers, and then take a practical test of assembling wooden puzzles, fitting pegs into holes. There were also odd bits of machinery to find out if we were mechanically minded. I had just one aim, to become a draughtswoman. When it was my turn to be interviewed by the Commanding Officer, she asked me what I would like to do. When I told her she handed me a huge book about architecture. She asked me if I understood it, and I told a deliberate lie. I said I understood it all. She obviously didn’t believe me, and said I was just the right type for a clerk. I tried to protest by telling her I could not spell. Her answer was, ‘None of us can’. So that was that. My case was lost. My heart sank – how boring.

16

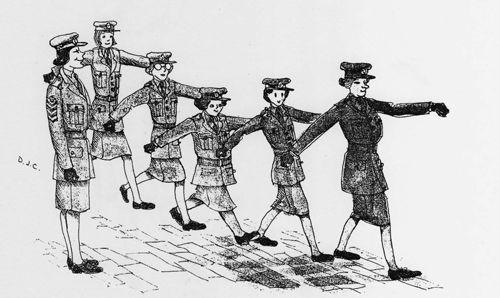

Joan ‘Panda’ Carter sketched some of her fellow ATS recruits on parade.

Barbara Rugg applied to join the ATS in 1938 and was put on a waiting list. In September 1939 she volunteered and although she was nearly 19 years old her mother opposed the idea, claiming that Barbara was ‘not strong enough’. However, the doctor declared her medically fit and her father signed the form. Barbara was in a group of twenty-four women sent for basic training to an army camp at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain. Their arrival was not welcomed and they were billeted, with bags of straw for bedding, in a redundant church; in fact, it was a tin shack that had just been painted, and the paint was still wet. While some of the younger soldiers, who had only recently been called up themselves, were helpful, the older regulars resented the women and booed them when they first went to the mess for meals:

It was awful to start with but we couldn’t write home and say so because our mothers would have been saying ‘I told you so!’ So we all kept quiet. I was there for two years and worked in the Drawing Office of the School of Artillery. There was a different atmosphere by then.

17

Jeanne Adams describes her experiences at the WAAF Depot in Morecombe in November 1941 as:

Very grim. It was terribly cold and we were all very young, very green and very, very, home sick. Our TAB injections made all of us rather ill for a couple of days and we lay under our miserably thin blankets wishing we could go home. It was interesting to observe, even at this early stage, that officer qualities came to light and revealed those who were going to lead us; they comforted us, urged us to get out of bed, eat some food and cheer up!

I was posted to Medmenham, but first I had to get there. There was only one train and that departed at 6am from Morecombe. I was billeted one and a half miles away and the only way to get there was to walk. So at 5.30am I set off in pouring rain, carrying a kit bag and gas mask, a tin hat and a suitcase and clad in something called a ground sheet, a substitute for a mackintosh. They were standard issue and because I was small I kept tripping over mine, so I struggled along the front, feeling very sorry for myself, and caught the train.

18

On her first day at Morecombe, Jeanne had met a vivacious redhead, Sarah Churchill, the second daughter of the Prime Minister, who had become a stage dancer and actress in 1935. She married a well-known stage entertainer in 1936 against her parents’ wishes, but by 1941 her marriage was breaking down and she asked a rare favour from her father: ‘I had decided to join the Services and asked him to arrange it as soon as possible. I was in the WAAF within forty-eight hours.’

19

Felicity Hill (later Dame Felicity Hill, director WRAF 1966–69) was in the wartime Inspectorate of WAAF Recruiting:

One day we received a message telling us that the Prime Minister’s daughter, Sarah, would be coming to Victory House to join the WAAF. Sarah Churchill was then recently married to the comedian Vic Oliver. Mrs Oliver arrived in a very lively mood after lunch at the Savoy, and I interviewed her in the inner office. I smiled to myself as I went through the motions of asking her the usual questions for completion of the application form (though I skipped over Father’s Name and Address, and the question of references seemed inappropriate to Winston Churchill’s daughter). I enrolled her as a Plotter, told her something of recruit training, and looking at her beautiful and abundant red hair suggested she should have it restyled, for I shuddered at the thought of what the camp barber would do to it. Sarah was later commissioned as a Photographic Interpretation Officer, a branch in which she and many other WAAF officers did valuable work in detecting and deducing intelligence material from aerial photographs.

20

Jeanne Adams plotted where each photograph was taken on photographic reconnaissance sorties.

Sarah continues:

In October 1941 I became an Aircraftwoman Second Class. My choice of the WAAF was influenced by the colour of the uniform. I was enrolled and despatched on a long train journey to Morecombe for the inevitable ‘square bashing’ and wrote plaintively to my mother about the first few days, largely concerned, as always, with my appearance. The shoes were a particular horror – not a pair fitted, all were hideous and you simply could not do anything but ‘clump’ in them. We left for Morecombe at four o’clock in the morning to catch an eight o’clock train. We had to carry full equipment, including gas cape and gas mask strapped on one’s back – full-sized kitbag on one’s shoulder, smothered in an enormous topcoat and clutching a suitcase with civilian clothes in the other hand. I never imagined an eight hour journey could be a rest cure! It was a wonderful system though, watching a straggly bunch of nervous civilians change in about forty-eight hours into fairly passable looking WAAFs. Another forty-eight hours saw a change in deportment and manner, and one would march away with a look of pity towards the next bunch of sad-looking individuals being herded in the entrance gate.

21

Sarah Churchill, the Prime Minister’s second daughter, was a plotter before training as a photographic interpreter.

Although commissioned later, Sarah started in the ranks as an ACW2 clerk (special duties) and worked as a plotter at RAF Medmenham before training as a PI. She was respected as a hard-working, generous person who never used her illustrious parentage to ‘pull rank’.

Elspeth Macalister had read archaeology at Cambridge University, including the use of air photography, and her tutor, Dorothy Garrod, suggested that she apply to the Air Ministry to be a PI. Elspeth was duly interviewed, soon heard that she was accepted and in July 1942 met up with three other Cambridge graduates, Sophie, Ena and Lou, to travel to RAF Bridgnorth for ‘kitting out’. After getting their uniform they were herded into a large hall to complete an IQ test with rows of numbers and odd shapes to match, which Elspeth found extraordinary:

Next day were the interviews to help us find our niche in the war machine. I was interviewed by Theresa Spens – we had been in the same form at school and never liked each other. She showed no sign of recognition. She asked me if I could cook. ‘No’. Then she said, ‘We don’t know quite where to place you. Your IQ is very low – educationally subnormal’. I had just achieved a good Cambridge degree and muttered something about PI. I was ignored, obviously I was useless.

On the last day the postings went up. I was to go to RAF Duxford; having joined the WAAF to see the world I would be six miles from home! My work as an unskilled clerk in Sickquarters was to write out, in longhand, a list of the kit of aircrew lost on bombing missions – a sad job.

22

Women came to PI from widely diverse backgrounds and experience. Some were not long out of school, such as Pat Donald who volunteered for the WAAF in London with a friend, just before their eighteenth birthdays. They were sent initially to RAF Gloucester where they were so homesick that they would have left after four weeks (as they were entitled to do) but stuck it out as the inevitable ‘I told you so’ comments at home would have been even more unbearable.

23