Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos (9 page)

Read Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos Online

Authors: Christine Halsall

Pat Donald was just 18 years old when she joined the WAAF.

Many younger women were looking for adventure, while others had put their chosen careers on hold for the duration of the war, and several, including Dorothy Garrod and Charlotte Bonham Carter, were of an age that would have exempted them from conscription. By various routes all these entrants to the women’s services came to serve at RAF Medmenham, where a new era in photographic interpretation had begun.

Notes

1

. Muir Warden, Tom, a Canadian wartime PI at Bomber Command, interview with Constance Babington Smith, 1956/7 (Medmenham Collection).

2

. Lawton (

née

Laws), Millicent, conversation with the author, 2010.

3

. Chadsey (

née

Thompson), Mollie, correspondence.

4

. Holiday, Eve, interview with Constance Babington Smith, 1956/7 (Medmenham Collection).

5

. Palmer (

née

Ogle), Stella, written memoirs, 1990s.

6

. Morgan (

née

Morrison), Suzie, audio recording for the Medmenham Collection in 2002, and correspondence with the author, 2011.

7

. Westwood (

née

Bruce), Lavender, conversation with the author, 2010.

8

. Scott, Hazel,

Peace and War

(Beacon Books, 2006), pp.47–8. By permission of Hazel Scott. Also in conversation with the author 2010–11.

9

. Rice, Joan,

Sand in my Shoes

(HarperCollins, 2006), pp.3–4.

10

. IWM 8516 99/44/1 The papers of Section Officer Dorothy Colles, held by the Department of Documents a the Imperial War Museum and printed with their permisison.

11

. Benjamin (

née

Bendon), Susan, written memoirs, 2006.

12

. Collyer (

née

Murden), Myra, recorded memoirs, also conversation with author 2010–11.

13

. Hyne, Peggy, recorded memoirs, 2010.

14

. Benjamin (

née

Bendon), Susan, memoirs.

15

. Duncan, Jane,

Letter from Reachfar

(Macmillan London Ltd, 1975), pp.18–9. Reprinted by permission of the author’s family.

16

. IWM 4483 82/33/1 The papers of Sgt Joan ‘Panda’ Carter, held by the Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum, and printed by permission of her daughter.

17

. Mottershead (

née

Rugg), Barbara, recorded memoirs, 2007.

18

. Sowry (

née

Adams), Jeanne, written memoirs held by the RAF Museum, Hendon, and printed with their permission, also conversation with the author, 2009–10.

19

. Churchill, Sarah,

Keep on Dancing

(Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1981), p.58. Reprinted by permission of Lady Mary Soames.

20

. IWM 4782 86/25/1 The papers of Air Commodore Felicity Hill, held by the Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum, by permission of Dame Felicity Hill.

21

. Churchill, Sarah,

Keep on Dancing

, pp.58–9.

22

. Horne (

née

Macalister), Elspeth, written memoirs, undated, and conversation with her daughter, 2011.

23

. Muszynski (

née

Donald), Pat, conversation with author, 2010–11.

EARNING THE

A

RT

When the RAF took over the Aircraft Operating Company at Wembley in January 1940 to become the centre for photographic interpretation, it also assumed the responsibility for training the increasing numbers of new interpreters that were urgently required. Instruction was undertaken by a number of the PIs already working at the newly named Photographic Interpretation Unit (PIU), most of whom had acquired their specialised knowledge of military targets by applying and adapting their previous civilian knowledge of air survey. Squadron Leader Alfred ‘Steve’ Stephenson was put in charge of organising all PI training courses for the RAF from the early days at Wembley until the end of the war. He was well qualified for the post, being one of the first geographers to use aerial survey on Arctic and Antarctic expeditions in the 1930s, with a wide knowledge and experience of the photogrammetric and optical machines associated with survey and PI. In Antarctica, a colleague had said that Stephenson was the ideal companion in difficult conditions: equable, efficient and with great organising ability. He had infinite patience with students, a quality he shared with Douglas Kendall, another pre-war air surveyor and mathematician, who would later be responsible for all PI carried out at Medmenham. Soon, RAF selection boards were identifying suitable candidates who showed the attributes required for interpretation training. From the middle of 1940, these included WAAFs who had by then served their regulation first six months in the ranks; Mollie Thompson was one of the earliest candidates to join a PI course at Wembley.

Finding enough space for courses to be run became a problem after bombing raids had damaged the PIU main building and damaged or destroyed many houses in the Wembley neighbourhood. Ann McKnight-Kauffer and Constance Babington Smith met on their PI course in December 1940, held in the upstairs room of a small terraced house opposite the PIU. It was bitterly cold and as the gas fire only operated intermittently, they wore their thick woollen WAAF greatcoats all day. Fortunately there was a canteen on the premises where they could warm up with tea and stodgy buns, or sausages known as ‘bread in battledress’. Their group of RAF and WAAF students learnt the skills of interpretation using recent photography taken over Germany and France, identifying ships in Kiel Harbour and analysing a dump of tangled French aircraft on an airfield at Bordeaux. In her final oral exam Ann was asked a catch question: were there more armoured divisions or horse-drawn ones in the German army? She fell into the trap and guessed ‘armoured’, which was wrong, but it taught her the basic principle of never making an assumption or a guess.

PIs were instructed that, if less than totally convinced of the identification of an object, they were to use the terms ‘possible’ and ‘probable’. For instance, they might be positive that what they were looking at was a tank and almost sure, but not quite, that it was a German Tiger. So they would describe it in their report as a ‘probable Tiger tank’. On the other hand, with the tank wreathed in smoke and impossible to clearly distinguish, they would describe it as ‘a possible tank’.

Ann was impressed, above all, by Kendall’s kindness and even temper to all the students on the course, and this was a feature of teachers found by prospective PIs on subsequent courses. The support, encouragement and patience of instructors were essential for students to gain self-confidence in their own knowledge and decision making. They would soon be writing reports on photography that they had interpreted, which could result in an immediate tactical response or affect future planning; in either case, loss of life was possible if action was undertaken based on an inaccurate report. Much could be gained by students from senior colleagues’ experience and specialist knowledge, with each individual adding their own particular skills to the team. PI was an art that could not be learnt by rote or by following a set of instructions; that would be merely recognition of what is present and visible. Interpretation was about defining the unknown, and asking not only what and where objects could be seen but, all importantly, why they were there and the meaning that could be deduced from that knowledge.

With the move of the PIU to RAF Medmenham in April 1941, the School of Photographic Interpretation was established in the main building of Danesfield House. Joan Bawden arrived at Marlow, the nearest railway station, in May to attend the first course to be held there. Transported to Medmenham with her luggage in the unit’s motorcycle and sidecar, her first impression of Danesfield House, in common with most other newcomers, was one of amazement at the size of the place and its resemblance to a castle or an abbey. Initially Joan, Helga O’Brien and two other WAAFs shared a small, bleak room above the stables, but within a week they were moved into more salubrious accommodation in the main building, a room with lattice windows, window seats and a view over one of the courtyards.

By the following year, Medmenham had grown to such an extent that, despite the rows of Nissen huts erected in the gardens, the space taken up by the PI school was needed for working sections. The school made two temporary moves before settling into its final wartime home at RAF Nuneham Park, just south of Oxford and a few miles from Benson and Medmenham. Nuneham Park was a handsome Palladian-style villa built for the 1st Earl Harcourt in 1756, surrounded by a park landscaped by ‘Capability’ Brown. After being requisitioned and designated RAF Nuneham Park, it housed the model-making school, part of the Photogrammetry Section and the School of Photographic Interpretation. As with Danesfield House, accommodation huts and temporary buildings, including a theatre, sprouted in the grounds and the Thameside mansion became another Allied Joint Service establishment. PIs drawn from all three services of the Allied forces were trained here, although as the need for PIs increased, army and ATS personnel attended similar courses at the School of Military Intelligence in Matlock, Derbyshire.

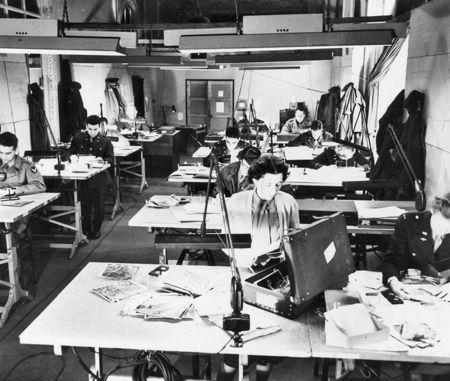

American personnel in the PI School at RAF Nuneham Park.

Diana Byron had grown up in Newlyn, Cornwall where she enjoyed living near the sea and watching the movements of ships. After training as a teacher at the Froebel Institute, she took a post teaching art at a boy’s preparatory school, where she was the first woman to be appointed to the teaching staff. With the declaration of war Diana joined the WAAF and trained for radar work at RAF Cranwell. Postings to two Chain Home radar stations in Kent followed; her work was to pass the details of incoming German aircraft (‘bandits’) to the appropriate group operations room, where WAAFs plotted them on to a central display table. The Chain Home ring of coastal stations formed the first area radar intercept system for the protection of Britain throughout 1940, when the country was threatened with invasion, and beyond. Later on, Diana was selected for PI training and attended the first course to be held at RAF Nuneham Park in 1942, where she and her fellow WAAFs were joined by WRNS, RAF officers and USAAF personnel. Diana said: ‘The course covered everything you could imagine, from silhouettes of shipping and aircraft and information about Europe. It was not only about aerodromes but also everything to do with harbours, seas, the whole lot – it was fascinating. What makes a good interpreter? Curiosity in the unusual.’

1

In the selection process for PI training, the candidate’s personal qualities were considered more important than paper qualifications. Visual memory, an ability to sketch and an attention to detail headed the list of necessary qualities, together with an enquiring mind and a sense of the significance of events and objects. Women were noted for their dogged pursuit of a particular subject over a period of time, while men often had scientific knowledge about a specialised subject. Under Stephenson’s guidance, his staff taught the principles and practice of photographic reconnaissance and interpretation and inspired the students to become ‘curious in the unusual’.

The first lecture of each course was an explanation of the three phases of interpretation, which was at the core of the efficient organisation of the examination of air photographs. From the early days at Wembley, where the system was devised, to the end of the war and beyond, it provided an effective means of prioritising the examination of an ever-increasing volume of photographs. Urgent prints were dealt with immediately, while those used for monitoring purposes were available within 12 hours, leaving others to be dealt with on a longer timescale. This deceptively simple system ensured that photography was analysed and reported on in a time frame dependent on its priority, and was used in Allied interpretation units all around the world.

First-Phase interpretation took place on the reconnaissance base that the photographic sortie was flown from, with the PIs living close to the airfield to ensure 24-hour cover. Photographs of high-priority targets were selected and analysed as swiftly as possible, or within a maximum of 2 hours of the aircraft landing. An immediate report was then signalled to the relevant command, which could trigger an instant tactical response if, for example, the PIs had sighted a concentration of enemy tanks or the departure of an enemy battleship from its anchorage.