1858 (35 page)

Authors: Bruce Chadwick

Brown grew a beard just before the Missouri raid; those who saw him said the long, flowing white beard gave him the look of a Biblical prophet.

Courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society

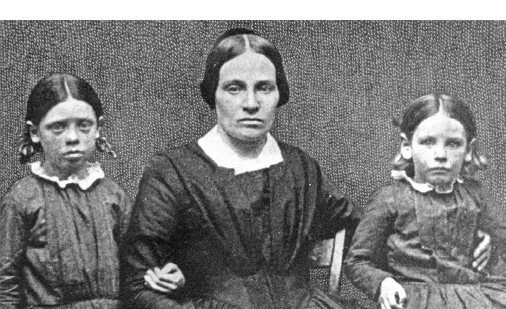

Mary Brown with two of Brown’s twenty children.

Courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society

One of John Brown’s final acts on his way to be hanged for his raid on Harper’s Ferry was to kiss a black child. The image helped to make Brown a martyr throughout the North.

Courtesy of the Kansas State Historical Society

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Eleven THE WHITE HOUSE

THE WHITE HOUSEOCTOBER 1858

During October, the last month of the 1858 political campaigns, the White House threw caution to the wind in its efforts to sink Stephen Douglas in Illinois, and decided to do it by any means possible. President Buchanan had used the phrase “honor” throughout the campaign, continually reminding leaders of both the Democratic and Republican parties that he would not engage in underhanded tactics in any race. Yet, as the historic debates in the Illinois Senate race between Democrat Stephen Douglas and Republican Abraham Lincoln ended in the middle of October it became obvious to all that the White House was willing to do anything to defeat Douglas.

The president never said a word about the unscrupulous campaign against the Little Giant, but everyone seemed to know that he was the one directing the attacks. The White House increased the tempo of its “dump Douglas” campaign because Lincoln had performed well in the debates. Lincoln had pinned Douglas down, forcing him to admit that he was just as much in favor of prohibiting slaves in the new territories, if the residents so chose, as he was in favor of slavery, if the residents so chose. Lincoln had also proved to the tens of thousands of Illinois voters who went to the debates, and to millions around the country who read about them in the newspapers, that he was the Judge’s equal as a debater, politician, and prospective U.S. senator. Lincoln, an underdog at first, had made up significant ground and in the campaign’s fading days had pulled even with Douglas in the race. Now was the chance, the White House decided, to aid Lincoln’s surge with a growing shadow campaign of duplicity and skullduggery.

The president, who felt the Oberlin abolitionists should be dealt with quickly and severely, threatened any Democrats who supported Douglas, reminding them that the president’s powers in patronage, federal funds, and political support could wreck their careers if they did not follow strict instructions from the White House. Buchanan was blunt, telling operatives around the country about the Douglas defectors, “I shall deal with them after the election as they deserve.”

440

Men who supported the president in his battle with Douglas were given railroad agent jobs so they could travel from town to town in Illinois to denounce the Little Giant. Friends sent him names regularly and reminded him that the prospective agents were authentic Douglas haters. The rail agents were even quoted in recommendation letters to the president. Buchanan’s friend, Isaac Sturgeon from St. Louis, in recommending a man name George Coles, told the president that Coles had publicly called Douglas “the basest traitor of our party.”

441

The administration located men from ethnic backgrounds to speak out against Douglas in Illinois’s many immigrant conclaves. Sturgeon advised Buchanan to fire Douglas’s officeholders throughout Illinois and replace them with administration men, but Sturgeon insisted that the new appointees’ ethnic background should match the largest ethnic groups in the area. In one area, he recommend Henry Oaverstabz, a German; he wrote the president, “We have the Irish vote. We must court the German vote.” Roman Catholics were recruited to criticize Judge Douglas in Illinois communities with heavy Catholic populations.

442

During the final month of the campaign, local operatives told the president which postmasters in Illinois sided with Douglas in the feud with the president and urged their removal, often suggesting strong administration supporters to replace them. One operative wrote, “The P.M. at Belleville, Ill., is a decided enemy if not really abusing his position. Trust no time will be lost in giving [a job] to Mr. Casper Thiell.”

443

Sturgeon urged the president to publicly attack any Democrats who wavered in their support of the attack upon Douglas. “We can not—dare not—sustain Douglas in his charges against the Administration,” he insisted.

444

It also appears that the administration coerced newspaper editors in Illinois and elsewhere by buying additional political ads if the paper came out for Lincoln against Douglas or urged its Democratic voters to stay home on election day.

445

Democratic newspapers around the country that supported the president were urged to run stories that were critical of Douglas, branding him a closet Black Republican or worse, a closet abolitionist. It was rumored in these stories that Judge Douglas was constantly meeting with Republican Party leaders and that he might abandon the Democrats to join the Republicans as soon as the elections were over. Democratic papers in Illinois then reprinted these stories to hurt Douglas’s chances.

446

And so, by October, as the voters of Illinois were deciding whether to return Judge Douglas to Washington or replace him with Abraham Lincoln, the White House crusade to undermine the Douglas campaign was at full throttle. The underhanded program was doing so well, in fact, that with just weeks to go before election day James Hughes, another of the president’s operatives in Illinois, wrote Sturgeon of the “dump Douglas” effort with great satisfaction that “we are getting along very well, and that we have most cheering news from all parts of the state. You will have seen that the president has gone to work in earnest, ‘chopping off’ heads in this state.”

447

President Buchanan was confident that his lieutenants in Illinois could defeat Douglas, and in so doing deny him the 1860 presidential nomination. All that remained now was to somehow derail the presidential ambitions of New York Senator William Seward, the certain Republican presidential candidate in 1860, so the Democrats could retain the White House.

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Twelve WILLIAM SEWARD: THE “IRREPRESSIBLE CONFLICT”

WILLIAM SEWARD: THE “IRREPRESSIBLE CONFLICT”William Seward, smiling and nodding to people in the crowd, sat comfortably on his chair on the stage of Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, on a Monday evening, October 25, 1858. It had been windy and raining all afternoon. A drizzle still fell on the city as several thousand people shuffled into the building to hear the famous New York senator, whom everyone expected to be president in 1860. Seward was about to give one of his traditional fire-and-brimstone stump speeches for the Republican candidate for governor of New York, Edwin Morgan. The speech was one of many planned for dozens of Republican rallies held that week as the gubernatorial campaign headed into its final phase.

448

Certain that Morgan would win handily, Seward, who was not up for reelection in 1858, had at first declined any interest in the campaign and went to Niagara Falls in September for an extended vacation with his family. Party leaders begged him to stump for Morgan, though, as the race tightened and a third, and then fourth, party nominated other candidates, creating a wide-open, four-way contest. He decided that it would be wise to leap into the race to clinch the governor’s mansion for Morgan and perhaps claim credit for a Republican sweep.

Seward had been introduced to the local political leaders on the platform earlier that night and waited his turn to address the crowd. It was one of hundreds of platforms he had shared with other Republicans. One of the most recent had been Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, who he joined at a rally in Boston a few weeks before.

449

The rain and wind caused problems with the lighting system and at first it was difficult for those in the crowd to see Seward because the lamps in the auditorium flickered from time to time.

450

Seward, who had arrived in town earlier that day by train, had no doubts about the speech he was about to deliver. It would be the New York senator’s traditional antislavery storm, full of thunder and bravado, denouncing the slavers and their supporters in Congress, embracing the support of God and the people in his cause to free the slaves, and ending with a call for the people to rise up, vote Republican, and send the hated Democrats home where they belonged. An advertisement the local Republicans ran in the Rochester newspapers that day to draw a crowd heralded the presence of one of the most famous men in America and promised a speech “which will be read throughout the country and exert a great influence in the present crisis of our affairs.”

451