Beginning Again (10 page)

Authors: Mary Beacock Fryer

Captain Clagett and a man he called Mr. Jukes were barking orders. Crew hauled up the sails. Out front on the schooner's jutting bowsprit were three small foresails, and aloft she carried topsails. The

Annabel

swung sideways as the wind billowed her canvas. We ran down the sound, flat Long Island to our right, the more rugged Connecticut coast on our left. The day was perfect, a fair breeze and strong sun.

A peep in the galley, reached by a companionway aft, revealed two bearded cooks, labouring before a brick oven with iron doors. An appetizing smell wafted from the small, cramped room. Beside it and below were the crew's quarters. That night we dined in the captain's cabin. A sailor served us, and our other company was Mr. Jukes, the ship's mate.

The voyage to Halifax was uneventful. August was a month when winds tended to be light and steady. When we went ashore the captain and mate came with us, for they had business to attend to. On firm ground I still felt the roll of the ship, and Captain Clagett was amused.

“”Still got your sea legs. That'll soon wear off.”

Halifax reminded me of Quebec, more for activity than appearance. Soldiers and sailors on and off duty were everywhere. Ships of the line, sails furled, rode at anchor in the huge harbour, and wharves lined the waterfront. Guided by Captain Clagett we found the harbour master, who knew which vessels were bound for Quebec. One, called

La Mouette

was about to sail.

“She's a fine brigantine,” Captain Clagett said. “Her master's Captain Pierre Kelly. Bit of a powder keg, being part Irish, but a good man for all that.”

He showed us a large hull with two tall masts and many yardarms. Captain Kelly spoke to us in French at first, but he switched to English at our blank looks. He had plenty of room, and he assigned Mama a cabin. Then he made me an offer I could not resist.

“Would you like to ship with me to Quebec, lad?”

“Wouldn't I just!” I replied eagerly.

“I'll refund half your passage money if you show you've a head for it.”

In a flash, deaf to Mama's objections, I began climbing the rope steps tied between two stays of the mainmast. At the topmost yardarm, tucking my toes into the safety ropes, I worked my way outwards and back again. When I looked down I felt dizzy, but the game was to look ahead. Gingerly I climbed back to the deck.

“You'll do,” Captain Kelly said approvingly.

Mama was not convinced. “We don't need to be that thrifty.”

“Please let me,” I begged her. “I'll never have a chance like this again And Papa was a sailor when he was young.”

“You won't let him do anything rash?” she asked the captain.

“Nothing I wouldn't do myself,” he replied.

I found setting the sails great fun as long as the breeze remained light, and the crew made good companions when I was off duty. In keeping with my humble station, I slept in a hammock below. The fun ended when, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence a storm blew up. Captain Kelly ordered us to reduce canvas before the pounding waves opened the timbers of the hull. With other crewmen I climbed the mainmast stays and crawled along the top yardarm to help furl a vast sail. What a job that was, fighting to gather up the sail without letting go the yardarm. Fortunately for Mama's peace of mind, she was feeling queasy and had gone to her cabin.

La Mouette

put into Gaspé Bay to ride out the worst of the storm. At the head of the bay was a village and mail and passengers came out in a whaleboat. Back and forth we tacked against both wind and current. Our progress was so slow that we began to doubt the wisdom of returning by sea. The land journey would have been more tiring, but we might be nearly home by now. Not until mid-August did we make Quebec.

“How long before we reach Buell's Bay?” Mama enquired as the ship's boat was taking us ashore.

“Eight to ten days,” I confessed uneasily. “I'll go to the Upper Town as soon as we land and reserve seats on the next stage.”

We were in luck. Two seats were available first thing in the morning. We stayed at a hostelry in the Upper Town to avoid the long climb from the London Coffee House. At Montreal we had to wait two days before a brigade would be leaving for Kingston. We took lodgings at the inn we had used on our outward journey, and tried to be patient.

“Let's go to my room,” Mama said. “It's empty and we can count our money in private.”

We found, thanks to Uncle Williiam's generosity and to my working passage, we had four pounds left over. Mama decided to take advantage of Montreal's lower prices to buy things we badly needed. With a light step she led the way. We window shopped till she had made up her mind where she could get the best bargains. She chose needles, thread, sugar and tea, and two large bolts of heavy wollen cloth, enough to make winter coats for everyone. Her last purchase was on impulse. We were taking a walk towards the mountain when she spotted a tinsmith's shop. She halted, rubbing her cheek with a forefinger, making up her mind.

“I'll do it,” she said firmly. “I'm going to buy a tub. It's high time we had baths. Let's see if the smith has one for sale. If not, I'll order one and have it sent in a later brigade.

A customer had cancelled an order and the tinsmith had a tub on hand. We lugged the awkward thing to our lodgings. With our original baggage and the items we had bought, we were loaded down by the time the brigade was ready. After we carried the tub to the docks, Mama stood guard while I fetched the rest of our things from the inn.

When we reached Buell's Bay, I left Mama with the baggage and hurried home to fetch our cart, hoping a horse would be there. I found Sam, who had ridden in on the mare to catch up on orders for the shop. In jig time we were back at Buell's Bay.

“Oh, my,” Sam remarked as he heaved our tub aboard the cart. “We'll have to haul lots of water to fill this.”

Mama laughed. “If I recall, Samuel Seaman, you'd lie in a bath as long as I'd let you.”

At home, Mama began giving lots of cuddling to Smith, Sarah and Stephen to make up for the two months she had been away. Robert and Margaret, however, clung to Elizabeth. To Mama's sorrow they did not remember her at first.

We told our story that evening as we sat round the hearth, a small fire taking the chill out of the early September air. Brazenly I fetched the grisly brush and decided to present it to Sam.

“Where'd you get that?” he asked, holding it up and waving it about.

“Promise not to laugh?”

“What's funny about a fox's tail?” he snorted scornfully.

“You remember Uncle William telling you about foxhunting?”

“Ridiculous,” he scoffed.

“Gruesome's a better word,” I rejoined.

With that I described the hunt. Arms akimbo, Sam listened. When I finished he threw back his head and bellowed. “Well, I never,” was all he could say.

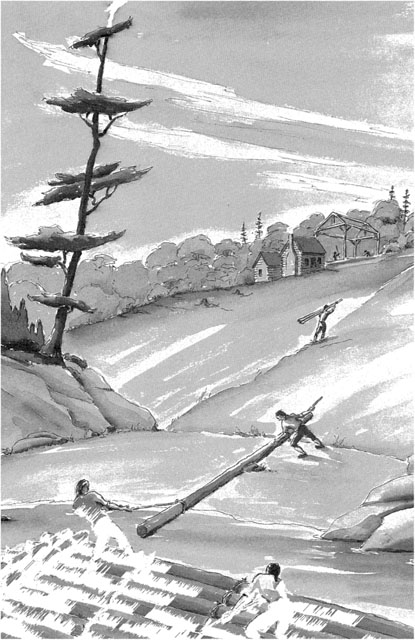

I helped Sam finish the ironwork, and we left together for our land, taking turns riding the mare, trailed by the twin fillies, now much grown. I could hardly believe my eyes when I beheld the great raft, though it was only half built. It floated in our bay, already almost as large as Reuben's. Cade and Papa, with the Mallorys, were tying another huge log that was floating loose, anchoring it with thick withies.

I hopped into the water at once and Papa had me pulling on a long willow strip to help tighten it till the log no longer shifted. Sam joined us as soon as he had rubbed down the mare and put feed out for her.

“Glad you're back, Ned,” Cade said. “And when it's dark you must give us a blow by blow description of your journey.”

“I'll like that,” said I. “And I know you will, too.”

Finishing Touches

N

ot till after we had tied another withy did I notice a huge wooden framework standing close to the sheds Cade and Sam had built the autumn before. “What's that?” I enquired of Cade.

“The next stage in our farm,” he said. “We're going to have a barn before winter, so we can store enough feed. Papa wants to keep all the horses here after we come back from Quebec. Raising the frame was fun. Lots of neighbours arrived and so many hands made the job quick and easy.”

“We won't have time to finish it before we leave with the raft, will we?” I asked. “Surely it will take us weeks to do the walls, floor and roof.”

“They're well on the way,” Cade replied. “The logs for the walls are piled inside the frame, and Mr. Coleman will soon send the floor and roof boards and shingles. We expect to have the barn up and the raft ready to sail before the end of October.”

That evening we lit a great fire. “Now,” said Cade as we were making ourselves comfortable round it. “Ned, it's time to hear about this marvellous journey of yours.”

I did enjoy being the centre of attention. Sam actually listened as I explained, often with Papa's help, who was who. “Even after shopping in Montreal, we brought home two pounds ten left over,” I finished my story.

Papa looked at me accusingly. “You can't possibly have done such a trip and made your purchases on so little. Did Uncle William help out?”

“Only with the passage on the schooner,” I said hastily. “Mama felt she could accept that without embarrassing you.”

Then I remembered Cousin Zebe's letter and fetched it from my bag. Brows knitted, Papa read it, folded it and stuffed in his pocket. “I'm pleased to know where some of our cousins are, but Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are so far away. I'll never have a reason to visit any of them.”

“Now that you've seen the place we came from, where would you rather live, Ned?” enquired Cade.

“Oh, here, of course,” I said stoutly. “I loved Long Island. But seeing how people live in an old settled place made me appreciate what we've built here. And we've really only begun.”

“Didn't you envy the relatives their wealth?” he asked. “Those fine houses?”

I was watching Papa as I replied. “No, I didn't. Their lives are different, but ours are just as good.”

“What did you make of your Uncle Isaac?” Papa asked me.

“He was polite, but I really did not talk with him much.”

Papa laughed to himself. “I guess he was feeling ill at ease. He used to be very proud that he was a drummer boy at Quebec under General Wolfe.”

“Was he indeed?” Cade interrupted. “Then you're two of a kind, Papa. Look how long you took over telling us about our past, our roots?”

“Now,” said I. “Tell me all your news.”

“We were here when Governor and Mrs. Simcoe passed by soon after you left with Uncle William,” Cade began. “They stopped in Kingston, and some people from here went to see them.”

“We saw Mrs. Simcoe, too,” I said. “Is Kingston our capital?”

“No, he went on to Niagara and called an election.” This came from Papa, which did not surprise me.

“I guess it's as well Mama missed that,” I said, though I was sorry I had. “Were there many fights?”

“None at all,” Papa admitted. We did not have a contest in our riding. Governor Simcoe had Mr. John White, the attorney general, run here. Mr. White is an Englishman who arrived in the spring. We thought we should not run anyone against a man the governor had chosen. We've some new names, though. The governor set up counties. Ours is Leeds. The one to the east, where the Sherwoods live, is Grenville. This township has been named Yonge.”

“Who decided on the names?” I was disappointed that our name would never grace the township.

“Governor Simcoe. He's calling all the townships after his friends, and the counties after British ministers,” Papa finished.

“What do people think of him, I wonder?” Sam asked.

Papa sighed. “The Yankees are saying the assembly that's to meet at Niagara later this month has no power. We'll have to wait and see what happens.”

“Meanwhile, we've too much to do here to worry about the government way off at Niagara,” Cade said. “Goodnight all. I'm off to bed.”

“Me, too,” Papa said, getting to his feet. “I want to take the bateau to Buell's Bay and go home for a quick reunion with Mama. I can't stay long, of course.”

We were all up early. By the time Papa left, we were levering another huge log into the water. Later in the day Jeremiah and Elisha Mallory arrived. The work on their own farm was caught up and they had time to help us again. We were adding a second layer of logs to the raft by that time, laying each log crosswise over the lower logs. The bottom layer was of white pine, but some of the logs in the upper one were of oak.

“Oak is heavy and floats so low that the surface of the raft would always be wet,” Cade explained to me. “Pine's lighter and will make the raft float higher in the water so we'll stay dry.”

“Reuben's raft was only one layer,” I recalled. “But all his logs were white pine.”

Later, Captain Sherwood rode in with Levius. They were on their way to Kingston, where Levius would stay for school. Samuel had had enough education, and would be helping his father with the survey work and the timber rafts.

“Lucky Samuel,” commented Levius.

When he saw Captain Sherwood, Cade came hurrying from the raft. “We could use some advice, sir, and our father will be at Coleman's Corners till tomorrow at least. We need a sailmaker and hope you know where the nearest one is to be found.”

“I have a man at Kingston,” the captain replied. “Would you like me to order a sail, made from the pattern he used for mine?”

“Please do, sir,” Cade said. “I have some cash here. Should I send it with you?”

“No, just write me a note. Once we know how much the sail will cost, you can arrange payment.”

When Papa returned the next day, he had Mama, Robert and Margaret with him. “I've come to give you decent meals and to watch the autumn colours,” Mama greeted us. “And I couldn't bear to think of the raft going without seeing it for myself.”

A few days later we postponed work on the raft in order to finish the barn. With six nearly grown men all helping we did not take long to pile log on log for the walls. Before we had the walls up, Captain Meyers arrived in his Durham boat. I seemed to be the only one who did not know why he had come when Papa called us to join him beside the boat.

“The boards from Coleman's mill,” Cade explained as we were running to the shore.” Mr. Coleman sent them to Buell's Bay by wagon, and Captain Meyers brought them along the river for us.”

His son Jacob was with him. “Hallo, Ned,” he greeted me. “That Yorker captain hasn't caught up with you yet, I see.”

I had to think a moment before I realized he meant Captain Fonda. Then I decided to make a good story out of our near encounter. “He came close in Albany a few weeks back. Staying at the same inn, but we eluded him.”

“What!” Papa exclaimed sharply. “You didn't say anything to me, nor did your mother. You mean you actually saw Gilbert Fonda?”

“It wasn't important, for nothing happened,” said I lamely, wishing I had not bragged to Jacob. Then I told them about Zebe putting the potion in old Fonda's drink, and about our stealing away at dead of night.

We unloaded the Durham boat and the Meyers left for the Bay of Quinte. In a surprisingly short time the barn was up. Cade and I then worked on stalls for the five horsesâthe stallion, mare, yearling colt and the twin filliesâand on feed bins. Hay had been drying in stacks and we carted it in and pitched it into the loft we had floored.

Mama, meanwhile, was making the cabin more comfortable between preparing enormous meals and sewing heavy coats from the cloth she had bought in Montreal. When she had a few moments, she sat on the great rock that extended from our shore, the one where we liked to dive, gazing out at the islands. They did look a picture. The reds of the maples were as bright this season as last. The sky was usually a vivid blue, with small wisps of white cloud, and none of us ever tired of the scene. An added attraction was the occasional ship that we could see passing above the western end of Grenadier Island. Some were merchantmen, but most were government ships of the Provincial Marine.

We really appreciated Mama's meals. The colder the days grew the more we seemed to need to eat. Wading in the St. Lawrence was becoming a very chilling business, and we were desperate to put the few remaining logs in place. At last the job was done, and Papa was satisfied that we had bound the logs with enough withies for the journey down the rapids. Next, we had to erect a cabin like the one that had protected us on Reuben Sherwood's raft, and the mast.

We chose a slender, straight white pine for the mast, and stripped it. Then Papa took charge of raising it. Though I had walked over the logs many times, I had not noticed the square hole, smaller than the bottom of the mast, in the centre of the raft. It had been left when the logs were being placed. Nor did I see the importance of wooden cleats on the front and on each side of the raft. Before we tried to lift it, Papa had Sam and me shave around the bottom end of the mast to make it fit into the hole. The thicker part above would keep it from slipping down.

Next came a halyardâthe rope we rigged to raise and lower the sail. Papa was most particular over that. He fussed with the rope and a wooden pulley he had made, watching it slip smoothly along the length of the mast.

“If the sail should jam and not drop at the rapids, we could lose control of the raft,” he said when we were growing impatient. “This has to work perfectly.”

Next, he attached the forward and side stays a third of the way from the top. Once he was satisfied that the halyard was running smoothly, we had to step the mast, and that was tricky, too. With all of us holding it along its length, Papa had us direct the bottom of the mast into the hole in the raft. Then we walked it up as high as we could reach. Papa took hold of the forward stay and pulled, calling on Sam and the Mallorys to help him. The tall pole rose steadily until it was almost at right angles to the surface of the raft.

“Hold it right there,” Papa shouted. “Ned, come here and help hold the stay till I look at the angle.”

He wanted the mast tipped backwards slightly, raked, he called it. That way the sail would pull better. He had Cade and the Mallorys fasten the side stays first, then several of us held the forward stay steady while Papa fastened it to the front cleat and wound the rope securely. Again, with the mast up, he slid the halyard up and down.

“Now,” he said. “All we need is the sail.”

He decided to take our bateau to Kingston to pick up the sail Captain Sherwood had ordered. It would be bulky, and with no decent road he could not use a cart. I would love to have gone along but I was not disappointed when Papa chose Cade to help him in the bateau. After all, the others had borne the brunt of the work for most of the summer. While they were gone, Sam and I worked on the raft's cabin, and with the Mallorys' help it was nearly ready when Papa and Cade came floating back from Kingston three days later.

We helped them spread out the huge lateen sail on a patch of grass. A slim yardarm was lashed along the top of the canvas. Papa examined the sail for a time before he figured out just how to raise it. Then we folded it carefully, moved it onto the raft, and unfolded it. Papa attached the halyard to the middle of the yardarm, and Cade and I hauled while Sam and he kept the sail from twisting about. Up the sail went without a hitch, and Papa showed us how to cleat the halyard tightly.

Mama came aboard to admire it. “You haven't lost the knack, Caleb,” she said to Papa.

“Wait till I see how it comes down,” he cautioned her. “Uncleat the halyard, Ned. Now, very gently.”

We strained against the line, letting out a little at a time. The sail descended to the surface of the raft as smoothly as it had on Reuben's. Papa was still not satisfied though. “Hoist it again!” Before we could cleat it, he shouted, “Now I want to see how it would work in a crisis. All let go now!”

We obeyed and the sail fell down, the yardarm making a bang as it struck the logs. Papa brushed an arm over his forehead. “I think we can trust that. If the wind pushes you where you don't want to go, at an island, for instance, you must be able to down sail in a flash. Even then a heavy raft will keep moving for some time, but we don't want the sail helping it along.”

Sam and I were used to keeping our feet on a raft, after being with Reuben, but Cade and the Mallorys needed practice. Elisha and Jeremiah had cowhide boots, which tended to slip more than our moccasins. Mama got busy and made pairs for them, sewing them with thongs as we sat by our fire after supper. One night she put down her work and was looking sad.”

“Penny for your thoughts, Martha,” Papa said.

“I'm thinking about Elizabeth, back at the house, taking care of things there. I wish she could have a break as I did.”

I thought she was giving me the opening I needed. “Could she come with us to Quebec City on the raft?”

“Would you allow her?” Papa asked Mama. “She would be as safe as any of us.”

Mama smiled. “I think that's a wonderful idea.”

“You'd be on your own, with the five youngest,” Papa said, looking doubtful. “Smith's still only eight. He tries hard, but he's not very big.”

“I could have one of the McNish girls come and spend the nights with me. I don't mind being alone with the children during the day. I'm not nervous about the nights either, but I would like company in case anyone takes ill.”

“Then that's settled,” said Papa. “As long as Elizabeth wants to come.”

“She'll jump at the chance!” I said confidently. I knew my sister better than anyone else. “I'd like to see her face when you tell her.”