Beginning Again (9 page)

Authors: Mary Beacock Fryer

“I'd never get used to that ride in a million years,” she said. Slowly the colour returned to her cheeks.

After a night at an inn in Montreal, we took a ferry to the south shore of the St. Lawrence. There we caught a stage for Fort St. Jean, a large army post on the Richelieu River. We slept another inn and rode eight miles by wagon to Ile au Noix, a fortress near the entrance to Lake Champlain. There we were in luck for a schooner was about to sail southwards. Flinging our baggage out of the wagon we raced to a ship's boat for the ride out to the schooner. An officer showed Mama into a cabin where several other women were quartered. Uncle shared one with other men, but I chose the fresh air on the rear deck.

The wind blew from the south. In the narrow lake the schooner rocked, tacking back and forth, crew bellowing as they trimmed sails. We could see each shore, and the ship had to work its way among several large islands. On both sides of the lake were outlines of high mountains, the Green Mountains of Vermont and the Adirondacks of New York, Uncle told me.

A day and a night of sailing and we reached the ruins of a very large stone fort. “Ticonderoga,” someone said. “Destroyed by the British during the revolution.”

Here the lake was very narrow, and a fleet of bateaux awaited the schooner. A short ride and we had to get out and walk. Rapids lay between us and Lake George, another long, narrow waterway that stretched into the heart of New York State. From Fort George, at the foot of this lake, we found we would have to wait a day for a wagon to take us ten miles to Fort Edward, on the Hudson River. I suggested we walk, and Mama was game. Burdened as we were, not only by bags but by the heavy coins in our money belts, I soon had second thoughts. Three very weary travellers reached an inn at Fort Edward that night. From there a sloop took us to Albany, now the capital of the state.

Albany was a shabby place compared to Montreal. A few wharves lay at the base of a steep bank. Uncle arranged for us to finish our journey aboard a sloop due to depart in two days' time. We clambered up the bank, passed through an opening in an old stockade, and made our way to the High Street. Now I was among familiar surroundings for Albany looked almost like Schenectady. The same tall houses overlooked wide grassy streets where cows grazed and pigs rooted. What a contrast this was to Coleman's Corners, where the houses were squat and far apart and fences confined the few cows and pigs.

Uncle led us to the inn he had used while on his way north. Mama shared a room with four other women, Uncle and I with two men and two boys. The night before we were to sail we were seated round a vast table with other guests, Mama between us. Suddenly I felt her stiffen, and I recognized Papa's cousin, Zebe Seaman, seating himself farther down the table. Uncle William rose to his feet as Zebe jumped up and came bearing down on us.

“Martha! What a delightful surprise. I had no idea you were coming home with William!”

At Zebe's friendly tone Mama relaxed. Rising and offering him her cheek to kiss, she said, “Zebe, what brings you to Albany?”

“The Legislative Assembly,” he replied. “I'm a member, and I have to come to meetings in this squalid town.”

Meanwhile I had risen and was standing by. Now he noticed me and stared hard. “Which son is this, Martha?”

At Mama's response, he gripped my hand. “My word, Ned, I'd never have known you. You have your father's breadth, but the look of the Jacksons still, don't you think, William? Now, let's find a spot where we can talk in private.

He ordered a table set up in a quiet corner. Talk we certainly did. Zebe wanted to know everything that happened to us since our flight from Schenectady. Mama was nearly through her recital when he suddenly interrupted her, his face serious.

“What's troubling you, Zebe,” she asked him.

“Gil Fonda. He may be at this very inn later tonight. He's a member of the assembly, too.”

Mama's face whitened, and I think mine must have as well. Uncle William rose to his feet in alarm. “We'd better find somewhere else to stay,” he said.

“I've a big room to myself here,” Zebe said. “I suggest all of you spend the night in it, and go to the sloop before dawn. That way he won't be likely to run into you in the public rooms or the hallways. Anyway, I shouldn't think he'd recognize Ned, or even you, Martha, after all this time. I'll sleep in the bed William and Ned have used.”

After we went to his room, Zebe had supper sent up, and we sat talking about the family. I listened more intently than when Uncle William had first arrived at Coleman's Corners, for I wanted to learn all I could about the people I would soon meet. About ten o'clock, Zebe excused himself.

Mama retired to the bed, which was in a dark alcove, and Uncle and I made do with armchairs. He soon dozed off, but I could not. A breath of fresh air might do the trick, but what if I bumped into Captain Fonda? The devil take him! As Cousin Zebe had said, I did look very different after more than two years. I refused to take fright at the mention of old Fonda. Out I went.

On my return, passing the tap room doorway, I spied Zebe, deep in conversation with the villain himself. So vivid was my memory that I had no difficulty recognizing Fonda even from behind. A flicker of doubt flitted through my mind. Could we really trust Zebe? I resolved to wake Mama and Uncle William well before anyone else was stirring and head for the sloop. I never closed my eyes, and when the tension was unbearable I roused the others, lit a lamp, and we closed up our carpet bags and Uncle's portmanteau. As we passed along the corridor, Zebe appeared.

“I was coming to wake you,” he whispered.

“Where's Captain Fonda?” I asked, half mistrusting him still. “I saw you talking with him last night.”

Zebe grinned at this accusation, every inch the plotter. “Blood is thicker than water, Ned. I slipped some laudanum into his whiskey, to make sure he'd sleep soundly.”

He escorted us through the town and down the steep bank to the wharf. Once aboard the sloop we thanked him for his kindness. He kissed Mama and shook our hands. “Godspeed,” he murmured. “I'll be home in a few days. Hope to see you then.”

We made good progress sailing down the Hudson River, and when we reached Manhattan we disembarked at King's Wharf. Uncle led us through the city of New York to a narrow brick house on Duke Street.

“I remember,” Mama said. “The Van Dusens live here.”

“They'll be happy to put us up for the night,” Uncle said.

Our hosts gave us rooms overlooking the garden at the back. We had a fine dinner and spent the evening chatting in an elegant drawing room. After a restful night we walked, baggage in hand, to the Long Island Ferry Dock. The oared ferry landed us in Brooklyn, where Uncle hired a chaise that took us barrelling along a smooth road towards Jericho. I gazed about me at a strange world that might have been mine, but for the fortunes of war.

“Everything's so civilized,” Mama said, sinking back on the cushions.

Without warning our driver drew up, and in the distance a horn tooted a long, flat note. Mama's eyes lit up. “The Brooklyn Hunt. We've stopped to let it pass by.”

A small red fox scampered across the road behind our rear wheels and vanished into the underbrush. On a hill the riders flashed into view, the hounds downslope in the lead. The pack scrambled through a pole fence, crossed the road and through a second fence. Noses to the ground they ran in confused circles round a pasture.

Thundering hooves shook the ground. Horses coughed and wheezed as men and women in high, round hats and scarlet coats jumped the fences and dashed over the grass. The hounds had scented something and were way out in front. I thought the fox was still in the underbrush. As we set off I saw him bolt back across the road, running away from the hunt.

“He's outfoxed them,” Mama said, chuckling. “The hounds are on a wild goose chase.”

“I wish Sam were here,” said I dryly. “He'd never believe this.”

Two Homecomings

T

he soft, to my eyes dainty, countryside unfolded mile by mile. Not long after noon we stopped at an inn for food and a fresh horse. The day slipped by and the shadows lengthened. Against a red sky Mama pointed out a neat square brick house set in a grove of trees.

“Uncle Isaac and Aunt Phoebe Seaman live there,” she said. “Papa's brother and my sister. Their children, Jonathan, Caleb and Abigail, are your cousins twice over.”

“Because two sisters married two brothers?” I asked. “Yes, Papa grew up in that house. Isaac inherited it when your grandfather Seaman died.

“Will we see it in daylight, Mama?”

“I think Isaac will invite us.” She sounded uncertain. Was there bad blood between Papa and his brother?

Uncle gave the driver some instructions. Guided by lanterns on each side of the chaise, we approached a brightly lit square building somewhat larger than Uncle Isaac's. A black servant in livery hurried down the few steps and opened the chaise door.

“Good evening, Mr. William. Welcome home,” he said.

“Jason! How good it is to see you. Kindly give a hand to Mrs. Seaman,” Uncle said.

Jason handed Mama down, took our bags and followed the three of us into a wide hallway. As Mama was anxious to freshen up, with Jason we climbed a broad staircase and he led us to two large rooms. Each had a four poster bed with a canopy and a soft thick carpet. After he lit the lamps and pointed to fresh towels in Mama's room, he repeated the little ceremony in mine. I poured water from a flowered china pitcher into a matching basin, and removed the day's grime. Then I put on a clean shirt, tapped on Mama's door, and we descended the staircase side by side.

“Such splendour,” I observed. “No wonder Uncle was so shocked when he first saw our house.”

We joined Uncle in his drawing room until Jason announced that supper was ready Uncle gave Mama his arm for the walk to the dining room. Over a meal of hot roast mutton Mama and Uncle discussed the people she wanted to see. Their elder brother, Uncle Townsend Jackson was high on her list, but she spoke of her hope to see Uncle Isaac.

“I've sent Jason to Isaac's to tell him you're here,” Uncle said. “And my groom will take a note to Townsend in the morning.”

After the port, Uncle rose with a yawn. Mama could hardly wait to return to her room, and we two followed her to the staircase. Uncle led me to his room and selected two suits which I tried on. They were only a little large, and he told me to borrow both of them.

The sun was well up when voices below wakened me. My room faced the front of the house, and I beheld two saddled horses standing on the drive below. A groom was loosening the girth on one. My curiousity aroused, I dressed in one of Uncle's suits and hurried downstairs. Mama was seated in the drawing room with a strange man and a lad about my own age.

“Your Uncle Isaac and Cousin Caleb, Ned,” Mama said.

From the way she was smiling I knew that Uncle Isaac Seaman had come out of friendship. I thought he looked less like Papa than cousin Zebe, but Caleb reminded me of Cade. For a time the two of us stood awkwardly, listening to Mama and his father. To break the ice, I suggested we go outside and look around.

“Pity you weren't here yesterday,” Caleb said when we were by ourselves. “The Jericho Hunt met, and we bagged a brace though we had to dig for one.”

“Foxhunt,” I said. I had not the foggiest notion what he meant but I was not about to display ignorance, at least not yet.

“We meet again day after tomorrow,' Caleb went on. “I know Uncle will lend you a horse. Won't you join us?”

I hesitated. If Sam heard I'd taken part in such an outlandish business I'd never hear the end of it.

“You do ride?” Caleb asked in a tone that implied I was some lower form of life.

“Of course,” I responded, nettled. Sam could go hang. I'd show Caleb I could ride as well as anyone on Long Island.

“I'll call for you at eight sharp,” he said. “Uncle usually rides, but I bet he'll stay home with your Mama.”

Uncle Isaac and Caleb left soon afterwards, and we had accepted an invitation to dine the next afternoon. Later, while we were still seated at our midday meal, we heard a coach rumble up the drive. The Townsend Jacksons had arrivedâand like a clap of thunder. Uncle Townsend's wife, Aunt Mary, was kept hopping about by their ten lively children. I could not keep them straight, but the clamour and confusion reminded me of home.

Mama looked radiant surrounded by her near and dear. Any feeling of guilt I had over not being home to help with the work was put to rest. I was glad we had come, but oh, the muddle over names! Uncle Townsend had a Samuel, Stephen, Elizabeth, Sarah, and Margaret. I could not tell whether Mama was talking about his brood or ours in Canada.

“Thank goodness Uncle Isaac has only three children,” I remarked when the noisy visitors had left. “I won't have trouble keeping them straight tomorrow.”

In good time Uncle's carriage, driven by his groom, set out for the Isaac Seamans'. This time I could see the neat brick house clearly. Like Uncle William's the door was in the centre, flanked by pairs of windows. Fields lay on either side of the long drive, three horses in one, cattle and sheep in the other.

“Why didn't Papa learn farming when he was a boy?” I wondered.

“On Long Island many landowners employ managers and have slaves or hired men to work their land,” Mama explained. “They don't make their livings only from farming.”

I knew that my grandfather Seaman had owned the schooner

Whitewings

. Uncle Isaac, Mama said, had a store in Jericho, and was still operating the schooner. Uncle Townsend had two ships that crossed the Atlantic. Uncle William had fifty acres, Uncle Isaac sixty-five, and Uncle Townsend eighty. Amongst them they had less land than Papa but to me they lived like kings. I found Cousin Caleb good company, though in my mind his name belonged only to Papa. Caleb's sister Abigail, a bit younger, was a tease who reminded me of our Sarah. Twenty-year-old Jonathan had taken

Whitewings

to Boston, a disappointment to me. I longed to see the ship Papa had sailed in his youth.

“With more than 200 acres you must be very rich,” Caleb said. “How many labourers does Uncle Caleb keep?”

He looked incredulous when I replied, “None. We do our own work, and we're not wealthy. We'll be better off once we finish our raft and sell some of our timber.”

I described our wilderness acres and the raft on which our future depended, but he only half listened. Our worlds were poles apart. I did not go to school and would become a blacksmith. He went to a boarding school in Connecticut during the winter, and hoped to enter a law office. Yet I did not envy him. Long Island was too finished. My family had a new country to build. After the first excitement had worn off, I thought life on Long Island would seem very humdrum.

The morning of the hunt, Caleb clattered up the drive. As well as a horse, Uncle William loaned me boots and a scarlet coat. The tall round hat was a bit loose, but a strip of paper inside the sweat band made it secure. With my deerskin breeches I looked as though I belonged as we rode away. The riders gathered before a tavern in Jericho, where what Caleb called the master of foxhounds and the whippers-in waited with the hounds. The landlord brought cups of brandy, and astride our mounts we downed them, rather too fast for my liking.

We trotted out of the village, hounds capering in all directions, noses to the ground. Their baying started as they scented something. We picked up speed, jumped a gate and circled a field in single file. It was planted with grain and we were careful not to damage it. From a clump of bushes a fox broke cover. The frantic little thing leaped through a rail fence and sped over some pasture. The horses jumped one after another and the hunt spread out. The fox was out of luck. Before it could find somewhere to hide the dogs were tearing it to pieces. The whippers-in arrived too late to stop the destruction.

“Pity,” Caleb commented. “The mask and brush are ruined.”

“Eh?” I queried, nauseated by the sight of the dismembered fox.

Caleb's look suggested I was an utter dunce. “The face and tail. Trophies to give to the best rider of the day.”

We got three more foxes, making what Caleb called two braces. We walked the horses back to Jericho to cool them. At the tavern where the hunt had assembled, the master rode up.

“Did you enjoy your day, young man?” he enquired.

“Yes, sir.” I lied, but what else could I say without offending anyone?

The crowning humbug was still to come. Someone called my name, and Caleb took charge of my horse and pushed me forward. The master held up a tail, dried blood visible on one end.

“For our Canadian visitor,” he called loudly. “A fine rider.”

I accepted the grisly trophy. Caleb and some of his friends thumped my heartily on the back and I did my best to look pleased. Riding home, I resolved to make an excuse if I were asked to hunt again. Much as I loved a good gallop, the reason for this one repelled me. Instead I accompanied Mama when she wanted to ride. She sat a sidesaddle, a long riding skirt draped over breechesâboth borrowed from Aunt Phoebe Seaman. One day, riding back from Uncle Townsend's, Mama looked at me in a strange way.

“I'd like to show you a house near here,” she said softly.

I did not need to ask who had once lived there. We turned off the main road and halted before a large white clapboard dwelling. Beside it stood a substantial stone building, great double doors open. Inside I saw several blacksmiths at work. I pointed to the stable yard visible beyond.

“Is that where the rebels seized Papa?”

She nodded. “Let's get away from here before I weep.”

I knew the rest. The rebels took Papa up the Hudson to a prison camp. When Mama heard where he was, she took Cade and Sam, mere babies at the time, and followed him. Papa escaped and they headed north. Eventually they settled in Schenectady and remained there until our flight to Canada. I felt haunted as we rode back to Uncle William's. The size of the shop had not eluded my eyes. Papa had sacrificed a lot for King George the Third.

The highlight of the visit, for me, came when Jonathan Seaman brought

Whitewings

into Oyster Bay and invited me aboard. Happily I climbed her rigging, but we hadn't time to sail in her. We had to get back to Uncle Isaac's, eight miles away, for supper. I liked Jonathan because he was very interested in my stories about the timber rafts, both the one we were building and Reuben's. The next day, back at Uncle William's, Cousin Zebe came to pay his respects. Before he left he gave me a letter for Papa.

“I'm sending him the names of the other Seamans who were Loyalists,” he explained. “A dozen families of our cousins are now in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. He may want to visit them.”

“Thanks, Cousin Zebe. I'm sure he'll be glad to know where they are.”

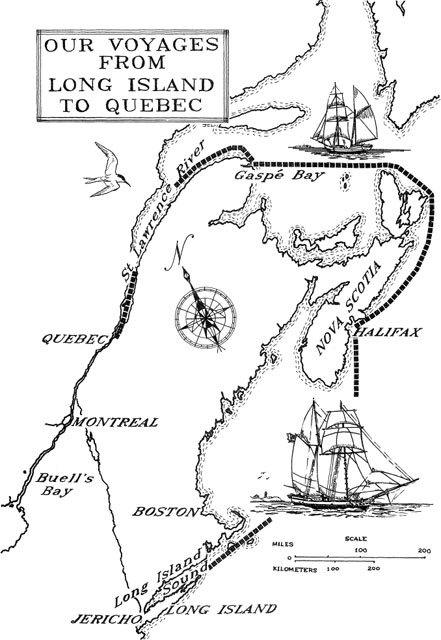

By the time we had been on Long Island three weeks, my conscience was really bothering me, and Mama was getting restless. When she told Uncle William we must leave, he had a bright idea. Why not go by sea? A ship of which he was part owner would be sailing for Halifax in a few days and we could have passage aboard. We would then have to pay only from Halifax to Quebec.

“Mama's jaw was set. “William, we'll pay all the way.”

“Fiddlesticks,” her brother countered. “If you won't let me do that much, I'll never come to Canada again to see you.”

“I'd love to go by sea,” I piped up, not wanting to miss the chance to sail on the Atlantic.

“Very well, and I'd better write to let Caleb know we're coming by sea,” Mama said.

“There's not much point,” Uncle replied. “You'll get home about as quickly as any letter even though you're taking the long way round.”

When the early August day arrived, Uncle William drove us to a tavern on the shore of Oyster Bay where all the relatives gathered to see us off. A schooner rode in the distance, sails flopping. While we watched, a ship's boat was lowered over her side and began moving towards us. We all trooped down to the shore as the oarsmen drew the boat upon the shingle. After kisses and handshakes all round, we stepped aboard. The crew put our baggage in and pushed off.

Mama waved, tears in her eyes, as we glided out into Oyster Bay. Suddenly I remembered! In these very waters the uncle whose name I bore had drowned. An eerie feeling swept over me that was broken by Mama.

“I'm sorry to leave, but longing to get back home to my dear family,” she said, dabbing at her eyes with a hankerchief.

My eyes were glued on the trim schooner whose great sides rose and fell, looming larger every minute. A sea voyage to Halifax! Another to Quebec! This would be a journey to brag about when we got to Coleman's Corners.

The name

Annabel

was painted on the schooner's hull. A rope ladder dangled down from the gunwale which a boatman caught and held steady for Mama. With considerable agility she gathered up her skirts and toe by toe climbed to waiting arms that hoisted her over the side. I followed, leaving the baggage to the crew, more experienced than I at climbing the flimsy, bouncing ladder.

Welcome aboard, Mrs. Seaman,” I heard a hearty voice boom above me. “Captain Josiah Clagett at your command.”

As I peered over the gunwale Mama was shaking hands with a burly man, weather beaten face partly hidden by a flowing beard. He did not look like the captain to me. He was dressed in the same garb as the crewâloose canvas trousers, woollen jacket and greasy pigtail at the nape of his neck. Captains of merchantmen, I decided, lived by less formal rules than officers in the Royal Navy. He led us down a companionway, his rather ordinary appearance outshone by a courtly manner. The port cabin, where we were to sleep, and his own to starboard, were the finest quarters on the ship, and he told us we would take our meals with him. Someone had hung a curtain between the two berths in our cabin, for privacy. Leaving Mama unpacking, I went back on deck, afraid of missing something.