Beginning Again (6 page)

Authors: Mary Beacock Fryer

“There aren't any to be had. I know Papa would part with the filly in order to buy a cow if one were for sale.”

Uncle pronounced his first night's sleep a sound one. Our home, he claimed, was much more comfortable than the inns he had used on his journey. Now, he wanted to be helpful, not just one more person who had to be looked after. He was no use to Papa in the shop, but he did not mind doing chores or helping about the house. Mama made him deerskin breeches and moccasins and loaned him a shirt of Papa's so he would not spoil the fine clothes he had brought with him. And the smaller children were better behaved than usual. Uncle enjoyed playing with them when Mama and Elizabeth were busy. Cade and Sam left with the stallion to continue the work on our land, but Papa stayed a while and he kept me with him to help in the shop. Sam promised to go hunting with Uncle when we took him to see our estate.

“How long can you stay, Brother?” Mama asked him when he had been with us a fortnight. As usual we were gathered in the main room of the old part of the house. The parlour was only for great occasions.

“How long can you put up with me?” he queried, grinning.

“The longer the better,” Mama said contentedly. “Please don't even think of leaving until late in the autumn. You had such a journey to reach us that a shorter stay would not make it worth while.”

Papa, coming in from outside, overheard Mama's words and repeated them. “In fact, why not stay for the winter, too, William?” he finished. “I'm sure you could make arrangements to be away from your estate on Long Island for as long as you wish.”

“I just think I might,” said Uncle. “And have a real experience of pioneer life, not just a taste. It would certainly give me something to talk about back home.”

Now Papa said, “We must make arrangements for you to see our so-called estate, and I'd like to take Martha and the baby along. We need to decide who stays here to look after things, and who goes.

“I guess I'll be staying,” I said, trying not to sound disappointed. With Cade and Sam already there, I was the logical one to be here, but I hated to miss watching Uncle's reaction to our land. Besides, Sam wouldn't be able to keep his promise to take Uncle hunting if he had to come home.

Papa shook his head. “You need a change, too, Ned. Now that your foot is healed, I would like you to ride the mare out and tell Cade to float down to Buell's Bay in the bateau. I know he won't mind taking over here, caring for the animals and working in the shop and garden. Everyone else may come to our land. I want to show Mama the changes we've made since her first visit.”

“I'd love that,” Mama agreed.

“So would I,” Elizabeth spoke up.

“The cabin won't hold half of us,” I observed. “But that won't matter at this time of year, unless it turns very rainy.”

We began preparations for the short journey, organizing extra food, clothing and bedding. Before I was ready to set out with the mare and her colt, some well worn copies of the

Montreal Gazette

arrived. Our turn had come to read the only news that penetrated our wilderness world. As soon as Papa had time to sit down, he picked up the newspapers eagerly and began leafing through them.

“Mr. Buell was correct,” he said. “We're to have a new province, Upper Canada, with our own governor and a legislative assembly. High time, too.”

“Will that mean an election, Papa?” I enquired. From what he had told me about elections, they were interesting.

Mama, however, looked disapproving. “Politics! I've enjoyed not having all that quarrelling. You know how much I worried that you'd get hurt at those meetings.”

“Martha,” Papa tried to sound soothing. “I never came home with more than a black eye when we lived on Long Island. In Schenectady I had to lie low for fear someone might discover I was a Loyalist. Here I'm a Loyalist among Loyalists, and can speak my mind again.”

“I'm sure meetings here will be wild, with so many Connecticut Yankees about,” Mama said. “They're madder than Long Islanders when they talk politics.”

“I think we should change the subject,” Uncle William said. “The more I ponder, the more confused I become over how one goes about building a timber raft. It seems such an enormous job of work.”

“It is,” Papa admitted. “Last season I served on a work crew in order to learn how to handle heavy logs safely.”

At that a thought struck me. “If I take the mare, how will you move your supplies to Buell's Bay for the bateau ride?”

“I know Dave Shipman will bring his horse to pull the cart,” Elizabeth said.

That gave me food for thought as I set out the next day, a pair of bags containing supplies slung over the mare's rump behind me. I could not help feeling jealous. Elijah Coleman and Jesse Boyce were friends, but Elizabeth was my very best friend. In my dreams I still hoped we would live together when we were grown up. At nearly fourteen I disliked the thought that some day my sister might prefer to live with someone else.

Apprentice Raftsmen

A

s I rode along the track that roughly followed the river I felt a new sense of freedom. The mist of dawn was lifting and the colt frisked about, I was happy alone after having been cooped up at Coleman's Corners for so long. The time was now early September 1791, and Papa had told me Cade and Sam had harvested most of the grain and vegetables they had planted in the spring. They had planted cuttings from the old apple trees, but some years must pass before we would have our own fruit.

I stopped at the Mallory farm to rest the mare and allow the colt to suckle. Jeremiah and Elisha were at home with their parents, Mr. and Mrs. Enoch Mallory. During the summer and early autumn they had too much work on their own land to help us prepare logs. They offered me a meal, but I accepted only some cider since I had brought plenty of supplies. As I passed Billa La Rue's cabin, I did not see anyone round. I wondered again about the strange events of that moonlit night last autumn.

Sam was working on a huge trunk with his axe when I arrived, and near the cabin Cade was keeping watch on the potash kettle, slung over a fire. I was mystified until he explained what he was doing.

“We collect ashes from burnt branches and put them into the wooden chest. See those holes at the bottom of the chest? Below them we set buckets, and then we pour water into the chest in top of the ashes and let it soak through them. What comes down into the buckets is called lye. We boil it down to make it more concentrated. Then we put it in barrels which the brigades pick up and take to the merchant in Montreal who buys it from us.”

“I suppose I'm to take over from you, “said I, and I told him of Papa's order to take the bateau to Buell's Bay.

“I'll be glad to go,” Cade told me. “My shoulder's bothering me again, and I've had to leave the heavy work to Sam. I think you should help him. I can finish this batch before I leave here,”

“I expect you won't be able to do much in the shop,” I remarked. I hoped that Papa would not have many orders or he might send me back to carry on.

“I'll be fine in the shop. I only use my good arm while handling the heavy hammer,” Cade explained. “For chopping and sawing I need both arms.”

He set off the next day, with a new sail up in a southwest breeze. Sam had made the sail out of some old canvas he found on Grenadier Island. “I suppose it was left there during the revolution by some ship of the Provincial Marine,” he said.

Right after Cade left, Sam lived up to his old reputation for laziness. He went off to a new clearing on the next farm lot to the west, which belonged to a family named Smith. I was left to chop by myself, and he did not reappear until nightfall. The next day, however, he stayed, working hard. He did not know at what time to expect the bateau, and if he were missing when Papa showed up he would be in deep trouble.

I thought Uncle William's visit to our land would be the highlight of the autumn, but I turned out to be mistaken. We did give Mama and Uncle a fine reception. Uncle was suitably impressed with our trees and he did exclaim over the rustic cabin. He did admire the view of the islands, and he did not complain about sleeping in the bateau, his skin smeared with oily horse balm to ward off mosquitoes. And Sam did take him hunting and return with a fine buck deer. All these activities, delightful though they were, were overshadowed by the arrival, a fortnight after Uncle, of Captain Sherwood in his canoe. He had a special request to make of Papa.

“Mr. Seaman, my young cousin, Reuben Sherwood, has a raft ready to sail for Quebec. He's short-handed, and I think this is a fine opportunity for your sons to learn rafting before you take your own down the rapids.”

Papa, leaned on his axe and wiped his forehead as he thought a bit. “We do have a lot going on, Captain Sherwood,” he began. “But I think you're right. I won't be sailing with such a green crew next year if some of my boys get experience now.”

“Good,” the captain replied. “I'd like to leave with them at first light. Reuben's land is the west half of Lot Two, on the river a mile below Buell's Bay.”

“Sam and Ned may go,” Papa said, to my joy. “My eldest son's at Coleman's Corners and we don't have time to send for him.”

I could hardly contain myself, and Sam fairly roared with delight. Riding a timber raft promised the sort of excitement he craved. I knew he was dependable when he liked what he was doing, and I had no qualms about going with him. We were both in high spirits when we bid Mama and Uncle and the others goodbye the following dawn. Armed with food, warm clothing and blankets we joined Captain Sherwood in his canoe.

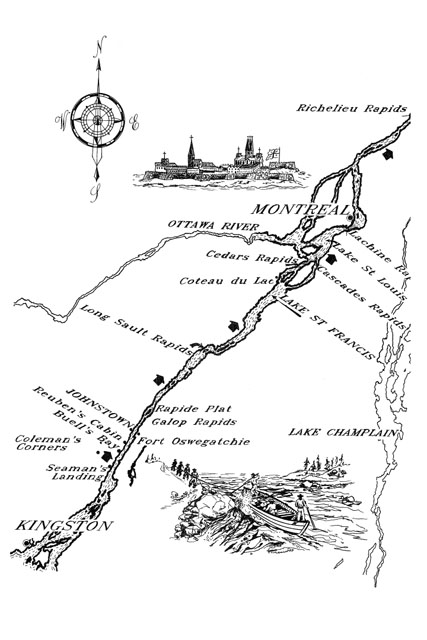

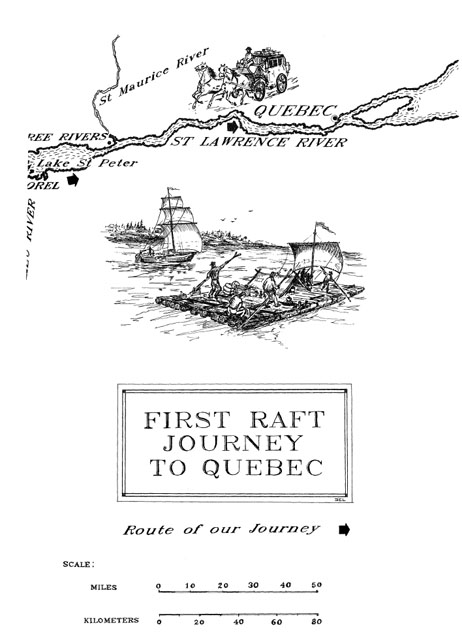

At first, Sam paddled in the bow, then I had a turn. I was surprised at what good time we made in the sleek craft., aided by wind from the southwest and the current of the St. Lawrence. We passed Buell's Bay in the late afternoon and soon spotted the huge raft tied to some trees that grew below a sandstone bluff. Since there was no beach, we tied the canoe to a jetty. On the raft I noticed a small log cabin for shelter, and a tall mast.

“Hallo, Reuben,” Captain Sherwood shouted. “Hallo!”

Before long a hefty young fellow with broad shoulders, a thatch of unruly fair hair over bright blue eyes, came down steps cut into the cliff and joined us on the jetty. “So, Cousin Justus,” he said. “You've brought me crew.”

“As I promised,” the captain rejoined. “Sam and Ned Seaman. Samuel and Levius will join you in good time tomorrow morning.”

This adventure was proving even better than I had hoped. We would have good companions, and I liked the look of Reuben, who seemed hardly older than Sam. Captain Sherwood waved as he slipped into his canoe to return to his farm in Augusta Township, a short distance farther downriver. Reuben had us stow our things in the cabin on the raft and invited us to supper. He led us up steps cut in the bluff to a humble cabin, not as big as the one on our land. He lived alone, he told us. His father, Ensign Thomas Sherwood, owned the next farm to the east,

“I was in the ranks of the Loyal Rangers when I was fourteen,” Reuben explained. “We moved here after the revolution. At first I lived with my parents and studied surveying with Cousin Justus, and helped build rafts. I only started pioneering on my own land last spring.”

His cabin delighted me. It was filled with the kind of clutter I longed to leave about, which Mama always insisted I tidy up. The meal was baked beans, swimming in pools of grease and chunks of pork, as sweet as sugar. Reuben must have put more molasses in his beans than Mama would allow. I thought them delicious, just right for my sweet tooth.

When we were ready to settle down for the night, we carried armfuls of cedar boughs to the raft, laid them on the logs inside the cabin, and spread blankets over them. The night was clear and dry, and we took our bedding outside and slept under the stars. The shrill call of a bluejay rocking on a weeping willow bough woke me. The sky was grey, but a tinge of light in the east showed that dawn was not far off. Before long sounds coming from the cabin atop the bluff told me that the rest of Reuben's crew had arrived. We tidied up our gear and climbed the steps in search of breakfast. Levius Sherwood was there, cooking bacon and eggs in a pan over a fire outdoors.

“Hello, Ned,” he called. “Glad you could come with us.”

Samuel Sherwood seemed pleased to see our Sam. Tagging after him was a lad of twelve. “Reuben's brother Adiel,” Samuel said. Then he called to a large black man who was arranging some of their belongings. “And this is Scipio, who came from Vermont when we did.”

“Scipio's come to keep us all in line,” Levius said with a wink. “Pa's sent him because he's sensible and Reuben's only twenty-two.”

“Young but experienced,” Reuben retorted. “Do you think my Pa would risk Adiel if he thought I wasn't dependable?”

We tidied up after breakfast, and Sam and I helped the Sherwoods stow their belongings in the raft's cabin. Next, Reuben showed us how to hoist the sail and cleat the sheets. Scipio shouted the orders that sent us to untie the various mooring lines. I knew he was a slave, but he acted as though he was accustomed to giving orders and to having them obeyed promptly.

Once we were under way we had little to do and I was able to study the shore. To my surprise I found a friend paddling a canoe as we swept along. It was Mr. Truelove Butler, who had accompanied us on our journey from Schenectady after we escaped from the jail.

“How are all the Seamans?” he called out.

“Very well indeed,” Sam replied. “When can you visit us?”

“One of these days I will,” he shouted back.

Soon Levius pointed to a large square-timbered house above the shore. “Our place,” he said, waving to a woman standing on a jetty. “That's Ma, come out to see us on our way.”

Before long we passed Fort Oswegatchie, on the south shore, with its memories of the British regular soldiers who had helped us cross into Canada. Next, on the north shore we saw Johnstown, the village of wooden houses that was our district seat. Our magistrates held court four times a year at St. John's Hall. A fleet of bateaux lay alongside the docks, and a tall sloop rode at anchor near the channel. I remembered our arrival here after our escape from Schenectady, and Mama's dismay when she caught her first glimpse of Johnstown. It did not look much different today. My thoughts were interrupted by a shout from Reuben.

“Galop Rapids ahead. Lower canvas!”

Scipio steered at the rudder while Reuben and Samuel Sherwood showed us how to loosen the halyard and keep it from tangling as the sail slid onto the log surface below. The drop down these rapids was gentle, eddies swirling along the sides of the raft. The sensation of speed was not alarming. Again at Rapide Plat the drop was gentle and we enjoyed the ride. As we were passing a large flat island I noticed we had slowed down. I helped hoist the sail again, and afterwards Reuben handed out chunks of bread and mugs of cider. Towards dusk the current was carrying us forward more rapidly Again we dropped the sail and for the second time Reuben shouted a warning.

“Long Sault ahead. We'll tie up here for the night.”

Scipio guided the raft gently alongside the bank in a sheltering bay. We crew members then had some busy moments, leaping ashore and finding suitable trees to which to tie the mooring lines. In the distance downstream we could hear the rumbling of the Long Sault. I already knew they were formidable, and dangerous.

For supper we caught some fish. Scipio made flat cakes of flour, eggs and water and fried them in a pan over glowing embers. I made a spit of green branches and skewered the fish before roasting them. That night we made our beds up round the fire and took turns keeping it going. The air had turned chilly.

Voices from the water roused us. A party of Indians in two long canoes was approaching our camp. Reuben was already up, which made me suspect he had been watching for our visitors. All of us rose to our feet, absorbed by the picture they made as they drew their canoes up on the flat shore.

Reuben nodded towards the newcomers. “Pilots for the trip down the rapids,” he explained.

“How did they know we'd be here?” I asked, bewildered.

“Scouts,” Reuben replied. “It's always the same. A raft arrives and there they are, Johnny on the spot. They're Mohawks from St. Regis, across the river. Sure footed as mountain cats. They like to earn hard cash guiding rafts through white water.”

We gave the Mohawks some tea, and they sat cross-legged in a circle, smoking their pipes while we had breakfast. Afterwards we helped them fell eight small trees and strip off the branches. Next they made a square crib, lashing the logs firmly together with withies. I watched carefully as they handled the long willow sinews. I would have to learn to twist them and tie firm knots myself before long. Then all the pilots began walking downstream along the shore. Sam and I followed until we could see the rapids, boiling and surging over the wide riverbed. Below us one of the Mohawks stopped, and the others kept on walking.

“We'd better go back,” I said reluctantly, for I wanted to see what the Mohawks would do next. “In case Reuben has anything he wants us to do.”

I must have looked confused, for when he saw me Reuben laughed and thumped me on the back. “The Mohawks take up positions all along the shore,” he said, pointing towards the rapids. “After we release the crib, they watch were it goes. That's the safest path. Then they come aboard with us. Each pilots the raft through the stretch of white water he watched, following the path the crib took.”

We waited and waited, until one of the Mohawks came to tell us the others were in position and we should release the crib. Everyone helped lever it into the water. Slowly it floated in the direction of the rapids, leapt forward, and vanished. Another long wait followed, until all the Mohawks came back. Now even Sam was looking anxious as we released the mooring lines and the raft began to move.

The guides seemed very cool. “Don't worry,” the one holding the rudder said when we suddenly picked up speed. “We've never lost a raft.”

I was not reassured. The roar of the water soon drowned out all conversation. Rolling waves towered above our heads, and I was convinced the waters would engulf us. We rose and fell, swung and swerved, the noise deafening. I was so busy hanging on that I scarcely noticed the Mohawks calmly changing places at the rudder, others nimbly running about with poles. The nightmare seemed never ending, but it probably lasted twenty minutes at most.

Then the danger was past as suddenly as it had begun. The raft moved slowly over smooth water. The pilot steered for shore, and I swayed as I stepped on Mother Earth, a mooring line in my hand. Sam, coming to his senses first, bent and kissed the ground.

“Whew!” he exclaimed. “Thank heaven that's over!”

Since he always appeared braver than me, I was glad the ride had unnerved him, too. After we tied up we all went to thank the pilots. Reuben went among them, shaking each man's hand and giving him some coins as he expressed his thanks.