Beginning Again (4 page)

Authors: Mary Beacock Fryer

Thus far Cade had been a mute observer. “I could take the letter straight to the postmaster, Captain Munro,” he suggested. “Samuel Sherwood said his farm's only five miles east of Johnstown.”

“I should have thought of that myself,” Papa said.

Mama's face brightened. “I'd feel easier in my mind if Cade put the letter in the postmaster's own hands.”

“I'll give you some cash, Cade,” Papa said. “You'll have to spend a night somewhere. There and back would be too long a ride for the stallion.”

“Not to mention my tail end after bouncing on his backbone,” Cade rejoined. “When our shipâer, raftâcomes in, let's order a saddle.”

Mama found some paper, purchased for the school she kept each afternoon for Smith, Sarah, Stephen and some village children. Papa slipped out and borrowed a piece of sealing wax from Mr. Abel Coleman, the miller and my friend Elijah's father. After Mama folded her letter and addressed it, Papa melted the tip of the wax over a glowing brand. He dropped a little on the edge of the paper and pressed it with his ring, engraved with the letter S.

“I'll go at first light,” Cade promised Mama.

She scarcely heard him. “This place!” she moaned, looking about her in dismay. “Where on earth can we put a guest?”

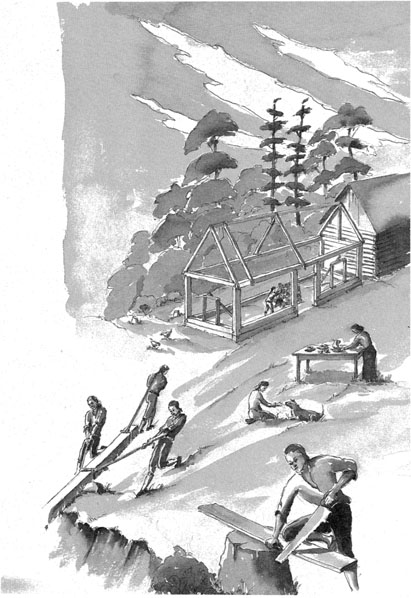

Papa rose and strode back and forth as he liked to do when he made a plan. “It's high time we had more room. We've lots of our own timber. The boys and I will fetch logs from our land for an addition, and I've enough cash to pay to have the timbers squared at Coleman's mill. We ought to be able to put up a two-room wing before the summer work. One will be a parlour, the other a bedroom for visitors.”

Mama put her arms around him, shaking her head. “You haven't time. We've new orders for the shop, and what about your plans for the raft?”

Now it was Papa's turn to shake his head. “We'll make time, my love. I won't have William going back to Long Island saying I'm not able to provide you with a decent home.”

Still Mama had doubts. “Suppose we do finish an addition. Will we have time to make more furniture?”

Of course,” Papa said cheerfully. “I wish we could hire a cabinet maker but I'd have to borrow money to pay him.”

“We mustn't go into debt,” Mama said in alarm. Then she had an idea of her own. “Sam, do you think you could turn out some nice pieces?”

“I'd like to try,” Sam replied. “I know I can go to Mr. Buell if I get stuck. He's a cooper by trade.”

Mama sighed happily. “More room and the thought of William's visit will make this winter fly by. It's lovely to have something special to look forward to.”

Cade was gone overnight taking the letter to Postmaster Munro's house. When he returned he proudly handed Papa some coins. “I didn't need much,” he said. “I bumped into Samuel Sherwood and he invited me to spend the night at his house after I'd been to the postmaster's.”

“How's Levius?” I asked.

“Groaning over his Latin. The schoolmaster at Kingston ordered him to work on it during the holidays for he's way behind in it.”

“Poor fellow,” said I. Being not so well off had its bright side. If Papa could have afforded it, he might have sent me to school, as he had done in Schenectady.

On Christmas day we held a special service in Coleman's barn, which was warmer than Boyce's field. I was less enthusiastic about our feast that followed. Before he left for our land, Papa had butchered the pig the McNishes had given Cade. We had made a pet of it, and I thought we had lost a friend.

“I feel like a cannibal,” I whispered to Cade as Papa began carving the roast that reposed on a wooden platter he had made.

“You're too tender-hearted, Ned,” he scolded softly, hoping no one would notice us. “Papa had to kill it for we don't have enough scraps from the table. We never leave anything on our trenchers, and we've nothing else for feed. We'll be lucky if the chickens, ducks and horses don't starve before spring.”

The work party that returned to our land was comprised of Papa, Sam and myself. Cade was to have a turn looking after the shop and helping Mama. With Papa there, Sam and I wouldn't get into many fights. We were delayed by heavy snowfalls early in January. When we finally did set out Papa was leading the stallion, our supplies packed on his back. We would not be riding him, to Sam's disgust. The snow lay so deep that even with snowshoes we sank down and found the going tough.

Now, joined by the two Mallorys, we began felling the trees in earnest. Each had to be chopped down with axes, then stripped of branches with our saws. Afterwards, driving the stallion, often with most of us pulling to help him, we moved each huge log close to the river shore. From there we would in time move the logs into the water a few at a time, and bind them together securely with long, pliant willow strips the Mallorys called “withies”.

February was bitterly cold and my toes got frostbitten. I had to stay inside for a few days, and Papa set me to brewing batches of spruce beer. We had trekked some potatoes and carrots from Coleman's Corners, but to save weight we had brought molasses and yeast, traded with Mr. Buell. The recipe was the one Mama had used to prevent scurvy during our first winter in Canada.

I heated about two pounds of spruce tips and two gallons of water in a cooking kettle. After it boiled I removed the spruce, added molasses and yeast to the liquid, and set the kettle near the hearth to ferment. The beer was a time-honoured method of warding off scurvy, learned from the Indians, and was every bit as good as fresh vegetables. I didn't care for the taste, but making it gave me something to do till my feet got better.

Early in March, a silly accident put an end to my life in the woods for some weeks. I, who had done very well with an axe cutting down huge white pines, let it slip while splitting kindling. The blade gashed my right foot, and a frantic Papa left Sam working with the Mallorys to take me home. After wrapping the foot to stop the bleeding he set me on the stallion and led him towards Coleman's Corners where Mama could give me the care I needed. I crossed my right knee and propped my injured foot in front of me. If the leg hung down it throbbed and Papa was afraid it would bleed again.

I felt about spent by the time we reached home. Mama, to my surprise, seemed to be watching for us though we were not expected. In jig time I was lying on my parents' bed, my wounded foot stripped of Papa's bandage and propped on two pillows. Mama squinted at it, brow furrowed. Beside her Elizabeth was looking all sympathy.

“Fetch my sewing basket,” she said. “This needs stitches.”

At that I could not keep from shuddering!

Stretched to the Limit

I

'd rather not remember the stitching. I suppose it did not hurt too much. After Mama washed the wound carefully, she drew linen thread through her needle and gently pushed it in and out till she had made seven stitches. Papa held me, his face the colour of a white sheet, and I wondered which of us might faint first.

“It's a gaping wound,” Mama told us. “It'll heal much faster with the stitches.”

The next day Papa returned to our land. Soon after, Elizabeth came in and told Mama that Dr. Jones, the only physician for many miles around, was in the village. “Would you like him to see Ned's wound, Mama?” she enquired.

“Yes,” she said. “And I want to see him about another matter.”

“I think I know why,” Elizabeth said softly.

Dr. Solomon Jones, who had been the surgeon to the Loyal Rangers, was tall and plump. Dressed in a black suit, he carried a black leather bag. He unwrapped my foot with surprising gentleness and studied Mama's handiwork. Then he replaced the bandage and straightened up.

“That looks clean, Mrs. Seaman. And there's no swelling to suggest it's septic. You did a fine job. Keep this young fellow in bed a few days. When he can walk on it without pain, take out those stitches and he can do whatever he feels up to in the shop.”

I determined to be back on my feet as soon as I could stand. With so much work facing us, I was angry at myself for being so careless with that axe. Elizabeth and Mama had put my straw mattress before the hearth so I would not have to climb the ladder to the loft. I spent comfortable nights, but during the day I thought I would go mad. Being in the midst of the chaos my younger brothers and Sarah created was nerve wracking.

Robert cried, Smith teased Stephen, and Sarah stubbornly refused to do anything when Mama or Elizabeth asked her to help. Once, in desperation, Mama chased Stephen to the loft, sent Smith to clean the stable, and paddled Sarah with a wooden spoon. Elizabeth was working at a new loom, expertly weaving linsey woollsey, ignoring the bubbub. Some village women had given Mama the flax and wool in return for teaching their children reading and writing. Elizabeh had strung the spun linen thread the length of the loom and was working a shuttle wound with wool.

“I don't know how you stand the confusion,” I complained.

She raised her head in wonderment. “I don't even hear it,” she said and resumed passing the shuttle back and forth.

“Isn't Mama a bit short-tempered?” I asked Elizabeth then. “She's usually more patient with Sarah.”

“True,” my sister replied. “There's a reason. It's the way she's feeling. Can't you guess why?”

“She did want to talk with Dr. Jones,” I recalled, a light dawning. “Another baby?”

“Yes,” she said. “In July, Dr. Jones thinks.”

“For your sake I hope it's a girl,” said I.

“I don't know,” she murmured. “She might turn out like Sarah.”

How glad I was when I felt able to escape to the shop. We had orders for nails, a very popular item with the customers. My shoulders were growing broad, and I liked flexing my muscles, bashing the hot iron with a hammer. For a while each day the foot did not feel too bad as I worked. When it began to throb I would give up and return to my mattress. One night Mama examined the wound and pronounced it much better. Again she called for her sewing basket and I began to quail.

“This won't hurt nearly as much as putting them in,” she said.

Actually it did not, though feeling the linen threads being pulled out was wierd. Now I was counting the days before I could leave for our land. Mama did not want me to go alone, and I must wait until Papa, Cade or Sam came to travel back with me.

In the end I stayed until well into the summer for so many other things had to be done before we could resume work for the raft. We would be planting crops amongst the stumps on our land, but again we enlarged the garden at Coleman's Corners. We needed every bit of ground we could clear if we hoped to feed all our animals through the next winter.

We had had barely enough for them through the past one. Our filly was very thin for we had given more grain to the mare because she was carring a foal. Our chickens and ducks were both pairs, and would soon nest. We added two kittens to our livestock, to deal with mice in the stable and to make sure none took up residence in the cabin. Smith made valiant efforts to help me, but he was still only seven and a light weight. We also had an order for some andirons, which kept me busy for days. I had never made any on my own before, and I was pleased at how well they turned out.

By mid-April our mare's time was drawing close, and I looked in on her the last thing before I turned in each night. I prayed that Papa, or even Sam who knew more about horses than I, would come home. I was out of luck. One night I could tell that things were happening, and I began my vigil by the mare, who had lain down, her sides heaving. Elizabeth came bringing blankets and hot tea, and settled herself to wait with me.

“She had an easy time last spring with the filly,” Elizabeth said. “Let's pray she does as well this year.”

Later, when the mare seemed in distress, I sent Elizabeth for Mr. Coleman in the hope that he would know what to do. Then, to my great relief the mare seemed to be managing on her own. She groaned and I saw two tiny hooves, then a nose, and without much more ado the entire foal slipped out, its head encased in a slimy film. The mare staggered to her feet and at once began licking the film to remove it. I found I had only to watch, for she was doing everything she should. By the time Elizabeth and Mr. Coleman came into the stable, the foal was standing on waving legs like long sticks, the mare still licking its coat to clean it.

“A colt,” Mr. Coleman said. “This is good news. A future breeding stallion. And standing so soon! He's a strong one.”

“It is a colt!” I exclaimed. I had been so absorbed watching the mare care for him that I had not thought to look earlier.

Papa returned with the stallion a few days later from our land. “I'm in a hurry,” he said. “Have to meet the boys along the creek with the cart. They're bringing two small rafts of logs for the new addition. We're going to run the rafts as far up the creek as we can, then take them apart and bring the logs, a few at a time, in the cart. Ned, I'll need your help.”

I could feel his eyes on my back as I went towards the cabin to tell Mama. Proudly I showed that I did not need to limp. The foot no longer hurt, but it did feel numb most of the time, which puzzled me. When I came out there was no sign of Papa, but I knew where to look. He was in the stable admiring the new colt, talking softly, stroking the mare's mane with one hand while the filly nuzzled his other. I knew he loved us more than his horses, but sometimes I wondered just how much more. Giving the colt a pat, he followed me outside and we hitched the stallion to our cart. A rough track followed the creek for a bit as it wound its way out to the St. Lawrence about ten miles west of Buell's Bay. We had gone perhaps halfway when we heard Sam's “Haloo” from the water.

“Can you come much farther?” I called, running down the steep bank towards the sound.

“A little way yet,” Cade called.

“Help me turn the cart, so we can follow them, Ned,” Papa shouted now.

As the track was very narrow there was no room for the stallion and cart to turn. We had to unhitch the horse, swing the cart around by hand, and hitch him up again.

“I'm pleased they're this far up, with that strong current against them,” Papa said, grinning with satisfaction.

“Can you get much higher?” I called, again running down the bank towards the stream.

“Sure,” Sam shouted. “We're going right to the mill.”

I kept going until I could see the two rafts, Sam and Jeremiah on the lead one, Cade and Elisha a short distance behind. The rafts were of white pines, to be squared for walls and cut into boards, and on top of each lay some cedar logs for the shingles. Sam tossed me a rope that was attached to his raft, and leapt ashore. Together we hauled the raft round a bend while Jeremiah steered with the rudder. We kept going along the winding creek until we were close to the swift waters which frothed below the mills. From here we could quite easily carry each log, and would not need to use the cart. We were already removing logs from the raft when Papa joined us.

“I'll take the stallion home. We won't need him,” said he.

I went to help Cade and Elisha with the second raft, and we hauled it along until dusk. Tying it securely to some trees, we walked home for the night. We were back at dawn, pulling it and taking turns manning the rudder. By the time we got as close to the mill as we could, there was no sign of the other raft for all the logs were piled outside the mill. We were not long in demolishing the second raft and carrying the logs to join those from the first.

Mr. Coleman bustled about giving orders. Hired men heaved the first log in position in front of the saw and started squaring it. Other timbers followed, then they started cutting boards, for floor and roof. While they prepared the wood, we were back at the cabin building a fieldstone chimney for the middle of the addition. That way one chimney would provide fireplaces for both the guest bedroom and the parlour. We felt pressed for time with so many other things to be done, but neighbours rallied round as they always did when a house or barn was being raised. With many extra hands and our horses we soon had the frame up and were lifting timbers. Once the lower ones were in place Papa allowed for a window in each room.

We used wooden pegs to fasten the timbers. Iron nails rusted too quickly. Next came the roof boards. Then Cade and I made a trip to the sawmill for cedar shingles. We had no time to lose, for we had to finish all the planting both on our land and in the garden if we hoped to have enough food stored before winter. We did not expect to resume work on the great timber raft until after Uncle William's arrival, which might be quite soon now.

After we laid the floor of the new wing, Papa took the cart and drove off on a mysterious errand. When he returned he had a large square package wrapped in burlap. “Glass from Buell's store,' he said proudly. “Enough for the new wing and the old part, too.”

As could be expected, Mama was overjoyed. The ugly greased paper panes we had put in when we built the cabin kept out flies and mosquitos, but they did not let in much light. Papa made frames for the new windows, and fitted the glass in them before he exchanged the greased paper for glass in the old ones. Cade, Sam and I nailed panelling on the inside walls to make the two rooms snug against winter's cold. Before the end of May the addition was finished though bare. Papa and Cade went to do the planting on our land, leaving Sam and me to work on the furniture and help put in the garden.

“Mind, you two, no quarrelling,” Papa warned us. “And, Sam, I don't want to catch you leaving too much for Ned to do.”

“I won't, sir,” Sam said cheerfully. “Woodworking's something I enjoy, much more than the shop.”

We got along better than usual until before breakfast on the morning of June 4th. Sam said he was going to Buell's Bay for the day, but he wanted it kept a secret. Of course that made me ask why.

“The militia's drilling for the King's birthday, the way they do every year, and I want to be there,” he said.

Now I understood. Sam was not quite sixteen, and Mama would not want him to go. Cade would probably be coming from our land, but only able-bodied men over sixteen and under fifty had to turn out. “Will Papa be there with Cade?” I asked Sam.

“He turned fifty on his last birthday, in case no one told you,” Sam replied. “He's quite a lot older than Mama. Now, just say you don't know where I am if she asks you.”

“I won't lie for you, Sam,” I said firmly.

“That won't stop my going,” Sam retorted angrily.

In the end I need not have worried. Mama remembered what day it was. As we were seating ourselves round the butternut table to eat, she said, “Cade will be at Buell's Bay today, for the drilling. But I don't suppose he'll have time to come home before he returns to the estate.”

I sighed with relief. Sam would not dare disappear now, for Mama would know without asking where he had gone. Both of us did a good day's work on the furniture. We planned a chest, some chairs, a commode, a small table, and a bed for guests. Mama had collected lots of feathers for a mattress. Uncle William could not be expected to make do with straw like the rest of us. Our work lacked polish, but Mama was pleased with our first chairs, and she thought the chest really quite nice.

June was galloping by at an alarming rate. The best part of each day was helping Sam school our yearling filly. Some of our neighbours thought we were fools to spend so much time just breaking in a horse.

“We know better, don't we?” Sam said. “As Papa tells us, love works so much better than force. Sometimes I wish he'd be as gentle with me as he is with his horses.”

By the end of the month we thought Uncle William might arrive at any time and we redoubled our efforts to finish the furniture. The days turned unbearably hotâthe kind of sticky heart that sapped our energy. Mama suffered the most for her time was drawing close. We tried to be extra thoughtful, and Elizabeth took over running the house. The heat was still intense when Elizabeth asked me to fetch Mrs. Boyce, whom Dr. Jones had arranged to have stay with Mama during the birth. He sometimes delivered babies himself, but since he lived about ten miles away in Augusta, one of the village women helped unless he happened to be nearby.

“Hurry, Ned,” Elizabeth urged me. “Mama's pains are quite close together.”

“I'll ride the mare to our land and fetch Papa,” Sam said. “The colt will follow her so he can feed.”

“Please do, Sam,” Elizabeth said. “I know Papa will want to be here as soon as possible.”

When Mrs. Boyce arrived, the first thing she did was order everyone except Elizabeth out of the house. (With the new wing I no longer thought of it as a mere cabin.) Sarah refused to budge, even though Elizabeth wanted her to keep an eye on Robert.