Beginning Again (7 page)

Authors: Mary Beacock Fryer

“You bring the rafts,” one of the Mohawks said, head held high. “We'll get them through safely.” I thought he had every right to take pride in having such a useful skill.

The rest of the journey was fascinating, and I no longer had cause to fear the rapids. Each night we camped ashore or aboard the raft, fishing to add to our food supply. We floated across Lake St. Francis to the head of the Cedars Rapids. Again a crew of Indians built a crib and helped us steer the raft through them, and through the Cascades just below them. By that time the weather had turned piercingly cold on the water, and I bundled into all my extra clothes. We were now moving down Lake St Louis towards the Island of Montreal. At the Lachine Rapids yet another crew of Indians appeared on cue. Then we were sailing past Montreal itself, tumbledown stockade beside the shore, church spires in the distance, schooners and brigantines at anchor in the harbour.

“How I wish we could stop and see the city,” I said.

“We will on our way back,” said Reuben. “I've a list of things I must buy for myself and others. The timber merchants pay us in hard cash, and we always do our shopping in Montreal after we've sold a raft.”

Off Sorel, at the mouth of the Richelieu River, we had to be careful for a bit. A maze of low islands almost blocked the channel, and the water ran a little more swiftly. That spot was known as the Richelieu Rapids though they were nothing compared to the Long Sault, Cedars, Cascades, Lachine or even the gentler Galop and Rapide Plat. Ships were able to sail up the Richelieu Rapids to Montreal when the wind blew from the northeast. No one could take a ship upstream against any of the other rapids, no matter where the breeze came from. As we sailed, Reuben pointed out several important landmarks so we would find the right channel when the time came to sail our own raft. Below the Richelieu Rapids, as we entered Lake St. Pierre, several vessels were tacking about.

“They're waiting for the right wind to push them up the rapids,” Reuben said.

On this lake sail and current carried us slowly past flat farmlands, and on to a large town. “Trois Rivières,” said Samuel Sherwood.

“Three Rivers,” Levius added. “Samuel likes showing off his French.”

“That's where our iron comes from. From the forges of the St. Maurice,” said our Sam. “But it's awfully expensive.”

“Our Pa says there's lots of bog iron north of Elizabethtown and we ought to be mining it,” Levius remarked.

“That would be a godsend,” our Sam said.

We left Lake St. Pierre and soon walls of rock towered above us. Fortunately we always found a ledge with trees on it where we could secure the raft. “We're almost there,” Reuben called when we had been sailing eight days since leaving his farm. “That's Wolfe's Cove on the left. Plains of Abraham above. Quebec's just ahead.”

I looked up but nothing told me the city was at hand. The shore was steep, a vast mountain of rock that left us sailing in icy damp gloom. Without warning we rounded a bend and there lay a harbour lined with buildings and wharves. Ships with sails furled lay at anchorâbig ones with many masts and yardarms, much larger than any that passed our land.

“What enormous ships,” I said to Reuben.

“First rate ships of the line, those big ones,” he said. “They're Royal Navy. Beauties, aren't they?”

The harbour front was alive with uniformed men, red-coated soldiers, sailors in blue with loose white trousers. Many bateaux lay alongside the wharves, but Reuben found space for the raft. I noticed some boats like bateaux but larger as we tied up. Durham boats, Levius told me.

“Rum for all hands,” Reuben called, beckoning to us. “Can't risk anyone coming down with pneumonia.”

The stinging stuff made me choke and burned my throat. It warmed me right to my toes, though. Adiel, too, spluttered over the fiery drink, but the blue tint left his face. He grinned at me. “My first trip. I've wanted to come for ages.”

“The nice part's the city,” Levius said, cradling his rum with both hands and breathing the fumes. “We'll have lots to do while Reuben and Scipio are busy with the timber merchants.”

“Tonight, we'll have warm beds at the London Coffee House,” Reuben announced. “We deserve some comfort after so many nights outdoors.”

He pointed to a vast stone building with white wood trim and a red tiled roof. It faced the wharf with its back against the rocky cliff. Once our raft was secure we gathered our belongings and hurried to the hostelry. Inside, when Reuben ordered beds, the landlord looked us over.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Room for six and a place in the stable for the slave.”

“No,” said Reuben. “Our servant must have as good a bed as you offer any of us.”

“As you wish, sir,” the landlord replied with a shrug. “A room for seven.”

We were shown into a large chamber that actually had four wide beds in it, enough space for eight. The next thing that caught my eye was a giant teacup complete with handle under one of the beds.

“What's this?” I enquired, drawing it out.

Sam laughed. “Oliver's skull! I haven't seen one in years.”

At my puzzled look Reuben took charge. “It saves going to the privy by the stables during the night. The servants empty it.”

“The correct word is chamber pot,” said Samuel Sherwood. “The nickname was an insult to Oliver Cromwell because he ordered King Charles the First's head chopped off.”

“I wondered how it got that name,” our Sam remarked.

After stowing our things we went to the dining room where a blazing fire from the hearth cast a cheery glow. The warmth was what we needed after days out in the cold. All around us people were speaking French, and we caught only the occasional bit of English. A good night's sleep followed, and we five lads were ready to explore Quebec. Samuel and Levius would serve as guides. Adiel was as keen as Sam and me to see the greatest city in the country.

Over breakfast, Reuben told us we need not hurry. “You'll have all day. The merchant we've chosen is a hard bargainer, isn't he, Scipio?”

“You're a hard bargainer yourself, Mr. Reuben,” said the black man. “It's your Yankee roots.”

Breakfast over, we climbed the steep flight of stone steps that led from the Lower Town to the more opulent Upper Town. On top of the rock, the governor's residence and the finest houses and shops were to be found.

Of Two Cities

T

he day was fine and warm for so late in the autumn. By the time we reached the Upper Town, my head was swimming over the busy scene. Too much vied for my attention. Houses crowded against the cliff face. Mobs of people swarmed by in all sorts of garbâmen in loose shirts, leggings and bright knitted caps; women muffled in long cloaks; small children in homespun playing tag on the steps; black-robed priests; striding frontiersmen in buckskins; wealthy-looking people with powdered hair, clad in silks and velvets; men in tall round hats and tight-fitting pantaloons like Uncle William's.

Many buildings were of stone, others of brick. How splendid they seemed compared to our settlement with its square timbered dwellings and log cabins.

“That's the Chateau, the governor's residence, next to the citadel,” Samuel Sherwood said “Pa goes there when he brings a raft. He's on the council and has to see about affairs in our district.”

“Pa says Lord Dorchester's a good governor, but a cold fish,” Levius informed us. “He goes for a drive each afternoon. Maybe we can catch a glimpse of him.”

Close by a well-dressed man laughedâat Levius' enthusiasm, I assumed. Then he spoke to us. “If you hope to see His Excellency, you're too late. Lord Dorchester left in August for England on leave of absence.”

“Thank you for telling us, sir,” I said. “But it would have been fun to see the governor.”

The stranger eyed us, an amused look on his face. “Everyone's laughing over the reason he left.”

“We're all ears, sir,” said Samuel Sherwood.

“He dislikes Colonel Simcoe, the new governor of Upper Canada. The Simcoes are expected here almost any day, and Lord Dorchester left so he would not have to greet them. He would have gone to England even sooner, but he had to wait until he received the Duke of Kent.”

“And who is the Duke of Kent, sir?” I enquired, not certain I followed everything the man had said.

“King George's fourth son, His Royal Highness Prince Edward, the commander of the 7th Royal Fusiliers. That regiment is our garrison at present. Hark!” He lifted his head and we all listened.

“Fifes and drums!” Levius said. “It must be time for the garrison's morning parade.”

“Yes,” our new friend agreed. “If you wait a few minutes you'll see the Duke of Kent come from his quarters in the citadel to receive the salute. The regiment is now marching from the barracks on Buade Street.”

I was excited, but Sam looked ready to burst. He had often said he would like to be a soldier. Now he would be seeing a full British regiment for the first time, and, for good measure, a royal Prince.

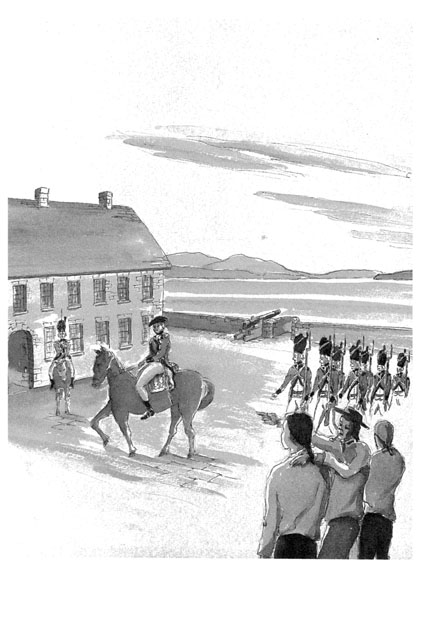

The music sounded much louder now. The Fusiliers were getting close to the square in front of the citadel. More people were gathering, attracted by the coming spectacle. Suddenly they started clapping, and the stranger who had told us so much pointed to the citadel entrance.

“Here comes the royal party,” he said. “The Prince is in the lead. He'll pass quite close to us.”

Coming towards us were half a dozen mounted officers, dashing in their red coats, gold braid and gleaming black boots, tall, close-fitting hats trimmed with black fur on their heads, except for the Prince. He wore a cocked hat with a brim so wide that it resembled a half-moon. We were able to see him very well, for he did ride right by us. He was a plump, burly man with a double chin and blue eyes that seemed to bulge from his face. For a Prince, and son of a King, he certainly was not handsome. The uniform, however, would have made anybody look grand.

He took up his station almost beside us, while the other officers brought their horses into a line behind him. On came the regiment, each company led by mounted officers, the rank and file on foot. In front marched a colour party bearing two flags. Beneath their red coats, which were trimmed with deep blue, the waistcoats and breeches of all ranks were dazzlingly white. The gold on the officers' coats and their sword hilts, sparkled in the autumn sunshine.

The parade ended, all too soon for us. The soldiers had marched past their commander, who now turned his mount and rode back through the gates of the citadel and was lost to view. All that remained, when the backs of the last redcoats receded, was the echo of the fifes and drums as the regiment returned to barracks.

“My, I'm glad we didn't miss that,” Sam breathed softly.

“It was quite a sight,” Samuel Sherwood agreed. “Where'd you like to go now?”

“Anywhere,” said I. “Everything's new to us so it doesn't matter.”

We followed the Sherwoods along the streets, often asking them to slow down as we gaped into the shop windows, astonished at the wonderful displays of goods. By late morning we found ourselves near the St. Louis Gate. From there we passed to the Plains of Abraham, where Wolfe had defeated Montcalm. I tried to picture the battle, but I could not. The vast sweep of green grass seemed a place of lasting peace.

Crossing to the edge of the cliff we looked over the St. Lawrence. I knew we must be above Wolfe's Cove, and I thought of yesterday when I had looked in vain from the raft for some sign of the city's presence. By what I guessed was noon, we were again hungry, and we re-entered the city through the St. Jean Gate. After a short walk Samuel Sherwood pointed to a small inn and suggested we dine there.

I looked at Sam, and he looked at me. “We don't have any money,” I said, embarrassed.

“You don't need any,” Samuel said. “Reuben owes all of us our keep. I have a little cash, and he'll repay me for everyone's dinner.”

“Good,” said our Sam. “That's settled.”

Inside we heard only French, and Samuel helped all of us order. A servant brought mugs of ale and a steaming platter of roast beef and potatoes. Lastly came a pudding loaded with fruit, dark and sweet with a strong flavour of rum.

“Where did you learn French?” our Sam wanted to know.

“During the war. At school in Montreal,” Samuel replied.

“Your family must have been in Canada a long time,” I said.

“More than fourteen years,” Levius answered. “I was born here. Ma came from Vermont with Samuel, our sister and Scipio.”

“Didn't your father come with you?” I asked now.

“No, he left home the year before. He was an officer in the Loyal Rangers by the time we came,” Samuel said. “Now, tell us how you came to Canada.”

“It was a bit over two years ago,” I said. “When the war ended we were in Schenectady. Our father hoped we could stay there. For six years we got away with it. Then a rebel officer had Papa and me thrown in jail, but we escaped.”

“That's an adventure to brag about,” Levius said.

“To tell the truth I was scared to death,” I admitted.

Now Samuel changed the subject. “I like Montreal better than Quebec. We always spend a few days there on our way home.”

We finished our meal and explored some more. By mid-afternoon we found ourselves at the top of the steps to the Lower Town and decided to return to the London Coffee House in search of Reuben and Scipio. Again the steps were cluttered with every form of human life and we almost had to elbow our way down. At the inn there was no sign of the men. Sam and Samuel headed for the taproom, but we younger lads did not want any more ale. Instead we loafed along the quayside in quest of further entertainment. A brigantine was unloading and we paused to watch hefty dock workers carrying barrels into a warehouse. Back and forth they trudged, shouting at one another good naturedly in French.

“Military stores,” Levius said. “The soldiers are guarding them.”

“Are they?” I asked, for I had not noticed soldiers about.

Now I saw that a few red coated men with muskets over their shoulders were standing near the ship. We walked farther and found a large schooner also unloading. For a time we tried to amuse ourselves guessing what the cargo might be.

“Rum from the Indies,” Levius suggested. “Sugar and molasses. Cotton from the Carolinas.”

“Trade with the United States?” I queried. Since our flight from Schenectady I regarded Americans as my enemies.

Levius nodded. “We're at peace, even though they're still hunting down Loyalists. Some of the rafts sold in Quebec come from Vermont and northern New York. Pa says the Royal Navy and the redcoats are here to remind the Americans that Canada belongs to Britain.”

“What goes out in these ships?” Adiel asked.

“Our raft, for one thing. Most carry timber,” Levius told us. “Or maybe wheat.”

By now I was getting hungry again, and bored by the small talk. After starting the day with the review of a royal regiment by a royal Prince, anything afterwards was a letdown. Levius and Adiel must have been feeling the way I was, for without a word they turned back for the London Coffee House. This time Reuben and Scipio were in the tap room with the two Samuels.

“There you are,” Reuben greeted us. “We've been waiting for you before going to get some supper.”

The meal was a merry affair. Everyone had mulled wine to wash down thick pies of veal and pigeon. Reuben said he had driven a hard bargain, as he hoped, and Scipio nodded in approval

“Scipio went eaves-dropping while I talked with the merchant, and he kept me informed on what other merchants were paying,” said Reuben. “That way I could not be fooled.”

“You hardly needed me, Mr. Reuben.” The black man was being modest, I thought.

“When do we start for home?” I enquired.

“Day after tomorrow,” Scipio replied. “Mr. Reuben has seats on the stage for Montreal.”

“I was hoping Upper Canada's new governor, Colonel Simcoe, would come while we were still here,” Reuben said. “But his ship must be delayed. It would have been nice to be on hand to see him land.”

“This morning we met a man near the citadel who said Lord Dorchester dislikes Colonel Simcoe,” said I. “If that's so, I wonder why.”

“His Lordship asked for Sir John Johnson, but the government in England chose Colonel Simcoe instead,” Reuben explained.

“Who's Sir John?” Sam enquired.

“”I'm surprised you don't know since you lived in Schenectady,” Reuben continued. “He was the largest landowner in the Mohawk Valley before the war. He lost a fortune in acres and mills. Now he lives at Lachine.”

“What will we do all day tomorrow?” Sam asked. Then I knew he regretted the query.

“Work our hearts out,” Samuel Sherwood replied. “Part of our job is taking the raft apart so the logs can be loaded into ship hulls. Then we have to pack our equipment neatly to make sure it will fit into bateaux and on the stage.”

We did do a hard day's work, from dawn till after dusk. First we demolished the cabin that had sheltered us. Then we cut the withies apart with axes and freed one log at a time. Meanwhile, crew from one of the ships took away each log as it floated from the rest of the raft. For a while we had to do without Reuben. He went to a local sawmill and sold the cabin logs to the owner, who arrived with a wagon to pick them up.

“I'm glad selling timber pays so well,” I said to Sam. “I suspect, by the time we've sold our raft, we'll have earned every penny twice over.”

“At least!” Sam straightened up from chopping a withy and rubbed his back.

I had trouble sleeping that night for I ached in every bone. And the night was a short one for we were up again before daylight. We had to carry our belongings to the Upper Town to catch the stage. The big, unwieldy coach could not descend the winding road down the steep hill safely, nor be pulled back up. We trundled up the stone steps slowly, loaded with bundles of clothing, blankets, cooking pots, coils of rope and the furled sail. The coach, with four grey horses hitched in front, looked gigantic, but when we tried to fit ourselves in we had trouble.

Five other passengers arrived, demanding seats. Scipio, the two Samuels, Levius and I rode on top with the baggage. I had to hang on, but it was better than riding inside on someone's knee. Poor Adiel suffered the humiliation of riding on Reuben's, for there was no more room on top. Changing horses often, and sleeping at inns each night, we reached Montreal three days later.

“We've made good time,” Reuben said. “When it rains a lot, the road's so muddy the coach may take a week for the journey.”

He found a room at a small inn, which he said was cheaper than the London Coffee House. After we stowed our things he sent Levius and me to find out when a brigade might be leaving for Johnstown and points west. Levius led me to the docks, and he made enquiries of several boatmen we found. The best we could do was on Friday. As today was Monday, we would have some time in hand.

“Reuben'll be disappointed,” Levius said ruefully. “I expect he was hoping to be off by Wednesday. I think two days would be all we need for shopping.”

Levius was wrong. Reuben was not put out by the delay. “That will allow time to hunt around for a good cow.”

“I'm pleased, too,” Samuel Sherwood said. “I'd like to look in on my school friends.”

Part of the time Sam and I walked the streets, deciding what we would buy in the shops once we had sold our own raft. Building castles in Spain, he called it. Wishful thinking, thought I. Even though a year seemed such a way off, we did have fun dreaming. One afternoon Sam went with Samuel to visit some of his friends. Levius, Adiel and I climbed the mountain that overlooked Montreal and sat watching the scene far below. Horses and people along the streets seemed like mere specks.”

The time passed pleasantly, though the weather was quite cold. By Thursday night we were again packing our things into bundles to take to the bateaux. A dozen of them were lined up when we reached the docks. The crews spoke French. Most of the passengers were from the Loyalist settlements in the area so recently separated to form Upper Canada. As we were loading our bundles, Reuben arrived with Scipio, leading a cow.

Getting her into the bateau proved awkward. Pushing and shoving achieved nothing. She stood with all four feet braced, her eyes wide with terror, her nostrils flaring red. Then Sam took charge, talking to her soothingly, and persuading her to step out. All our efforts had made her back up. Once she had stepped over the gunwale and onto the flat floor, Sam stayed at her head, crooning till she got used to the sway of the boat.