Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (38 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Among the most common icons of the American West is the quick-drawing, sharpshooting sheriff, facing down an outlaw at high noon on a dusty street as the anxious folks take cover. Indeed, most western tales seem to end with guns blazing, and when the smoke clears, only the good guys are left standing.

It is generally believed that six-shooters tamed the West, that a man couldn’t safely walk the streets without his Colt resting easily on his hip, and that the background music in most western towns was church bells and gunshots. The heroes were the men who shot quickest and straightest.

Contrary to the legend, not every man in the West carried a six-gun or was quick to draw. Gunfights were rare and mostly avoided if possible. As Doc Holliday learned, a big reputation was often more valuable than a gunslinger’s skill, because it prevented people from drawing on you—or, just as likely, shooting you in the back. In fact, in most towns, once they had been settled for a few years, it actually was illegal to carry a gun. In most places, people were much more likely to be carrying a shotgun or a rifle than a pistol, because they were much more likely to need a gun for hunting than for protection. The heyday of the gunfighter (or the pistolero, as he was often called) began after the Civil War, when many thousands of men came home with weapons and experience in using them. There actually were very few real showdowns, where two men faced each other a few feet apart and drew; they were so rare, in fact, that killing Davis Tutt on a street in Springfield, Missouri, made Wild Bill Hickok a national celebrity. And even in those few real duels, it rarely mattered who fired the quickest, but rather, whose aim was true. Most times, shooters would just keep firing until—or if—someone got hit. Weapons and bullets at the time were notoriously unreliable. As Buffalo Bill Cody once admitted, “We did the best we could, with the tools we had.”

So, while quick draws were impressive in the movies, in real life, they rarely made any difference in the outcome. In fact, as Wyatt Earp once explained, “The most important lesson I learned … was that the winner of a gunplay usually was the one who took his time.”

The notion of a fair fight was also mostly a Hollywood creation. Because it was a matter of survival rather than honor, in many shootings, the winner was simply the guy who got the drop on his opponent. Some

men carried a pistol on their hip, knowing it would attract attention—but when necessary, they’d pull their serious weapon, often a small derringer, from under a coat or shirtsleeve and fire before their startled opponent could respond. It has been estimated that as many three out of four people who died from gunshots were killed by concealed second weapons. When gunfights did take place, they generally happened on the spur of the moment, sometimes breaking out when people were liquored up and angry, and the shooters, rather than standing at a distance from each other, were only a few feet apart.

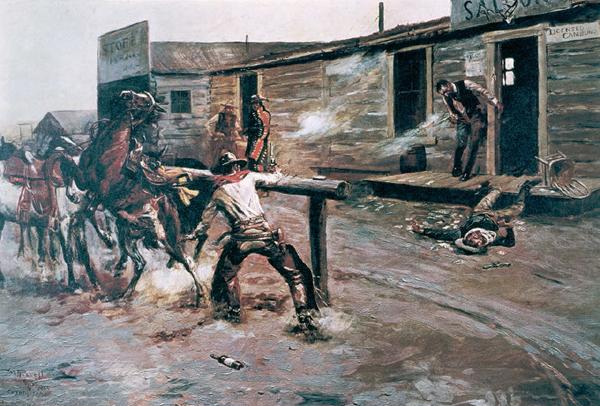

Charles Marion Russell, “the Cowboy Artist,” tells an Old West story in his oil painting

Death of a Gambler:

Cards, alcohol, and guns all come together in a saloon and lead to an inevitable result.

Most guns used the “cap and ball” system, exploding black powder-propelled “bullets” little bigger than a marble that were accurate only to about fifty feet. Bat Masterson was quoted as advising, “If you want to hit a man in his chest, aim for his groin.” If more than one person was involved, the situation quickly became chaotic: After the first few shots, the black smoke would have obscured everybody’s vision for several seconds, making it even more difficult to fire rapidly and hit a target with the next shots.

The truth is that guns and rifles were common and absolutely necessary in the West, but they were used more for hunting and protection than for two-gun shoot-outs.

BILLY THE KID

At about nine o’clock on the warm moonlit night of July 14, 1881, the sheriff of Lincoln County, New Mexico, Pat Garrett, rode out to old Fort Sumner with deputies John W. Poe and Kip McKinney. The famous fort had been abandoned by the army after the Civil War, and cattle baron Lucien Maxwell had transformed it into a beautiful hacienda. His family now lived in the officers’ quarters, while Mexicans occupied many of the outer buildings. Lucien himself had died, and his son Pete was now running the compound. Garrett had received some reliable information that the outlaw Billy the Kid had holed up there with his girlfriend. He and his deputies would need to be quiet and careful: Billy the Kid was a cold-blooded killer. Garrett knew that better than most: He had captured the Kid just six months earlier, only to have the outlaw escape the noose by killing two of his deputies—while still wearing chains.

The weather was pleasant as the three lawmen unsaddled their horses outside the compound and entered the peach orchard on foot. They saw people sitting around evening campfires in the yard, conversing mostly in Spanish. Somebody was strumming a guitar. Garrett and his men stayed silently in the shadows, watching, without knowing exactly what they were looking for. The sheriff intended to have a private conversation with Pete Maxwell, who was a law-abiding citizen. As they lingered, a man stood up, hopped over a low fence, and walked directly toward Maxwell’s house. In the firelight, they saw that he was wearing a broad-brimmed sombrero and a dark vest and pants; he was not wearing boots. They couldn’t see his face and didn’t pay him much attention.

To avoid being noticed, just in case the Kid was there, Garrett and his men backed up and took a safer path to the house. Around midnight, the sheriff placed Poe and McKinney on the porch, about twenty feet from the open door, and eased himself into Maxwell’s dark bedroom. Garrett sat down at the head of the bed and shook Maxwell awake. Speaking in a whisper, he asked him if he knew the whereabouts of the Kid. Maxwell was not pleased to have been woken, but he told Garrett that the outlaw had indeed been there for a spell. Whether he was still there, he did not know.

As they conversed, they heard a man’s voice outside demanding,

“¿Quien es?”

(“Who are you?”) A split second later, a thin figure appeared in the doorway. Looking back outside, the man asked again,

“¿Quien es?”

Even in the dim light, Garrett could see that the man was holding a revolver in his right hand and a butcher knife in his left.

The man moved cautiously into the bedroom. Garrett guessed he was Pete Maxwell’s brother-in-law, who had probably seen two men on the porch and wanted to know what was going on. The sheriff also knew he had a big advantage: The thin man didn’t know he was there, and it would take a few seconds for his eyes to adjust to the dark. The man walked toward the bed, leaned down, and asked Maxwell in a soft voice,

“¿Quienes so esos hombres afuera, Pedro?”

(“Who are those men outside, Peter?”)

It’s impossible to know what Maxwell was thinking at that moment, but just above a whisper, he said to Garrett, “That’s him.”

The thin man stood up and started backing out of the room. He raised his gun and pointed it into the darkness. As Garrett later remembered, “Quickly as possible I drew my revolver and fired, threw my body aside and fired again.” Garrett and Maxwell heard the man fall to the floor. Not knowing how badly he was hit, they scrambled out of the room. The Mexicans had heard the shots and were running toward Maxwell’s place. Safely outside, Garrett waited to see if anyone else came out. No one did. “I think I got him,” Garrett said finally.

They waited a bit longer, then Pete Maxwell put a lit candle in the window. In the flickering light, they saw the lifeless body of Billy the Kid sprawled on the floor. Garrett had shot him dead just above his heart. As Garrett concluded, “[T]he Kid was with his many victims.” The legendary outlaw was twenty-one years old when he was killed that night.

If he actually

was

killed that night.

No one disagrees that Billy the Kid was one of the most ruthless outlaws to roam the Old West. As the

Spartanburg Herald

reported, “He was the perfect example of the real bad man, and his memory is respected accordingly by the few surviving friends and foes of his time, who knew the counterfeit bad man from the genuine.” But since that night, when sheriff Pat Garrett fired two shots into the darkness, people have wondered who actually died on Pete Maxwell’s floor.

Few names are better known in American folklore than Billy the Kid. Although his life as an outlaw lasted only four or five years, he accomplished enough during that brief span to ensure that he would be remembered forever. The only authentic photograph of the Kid, a two-by-three-inch ferrotype, was sold at auction in 2011 for $2.3 million, at that time making it the fourth most valuable photograph in the world. It was a tribute to his notoriety.

Perhaps surprising for someone so well known, there are very few verifiable facts about his life. It’s generally believed that his name was William Henry McCarty Jr.—or, as he called himself, William H. Bonney—and that he was born about 1859, probably in New York City. He was the son of Irish immigrants who came to America to escape the Potato Famine. His father was long gone by the time his mother and stepfather opened a boardinghouse in Silver City, New Mexico. His mother, Catherine, tried to raise him right: He could read well and write in a legible hand; he was known to be polite and well mannered. But the New Mexico Territory was a hard place to grow up; gunplay was common, and the murder rate was high. The people who stayed at the family boardinghouse were on the move: miners, gamblers, merchants, women of pleasure, teamsters, and toughs. From these people, the impressionable boy learned the skills of survival. His proudest possession was a deck of Mexican cards; by the time he was eight, he could deal monte, and within a few years, he was said to be as skillful with cards as any of the gamblers in the local saloons.