Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (40 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

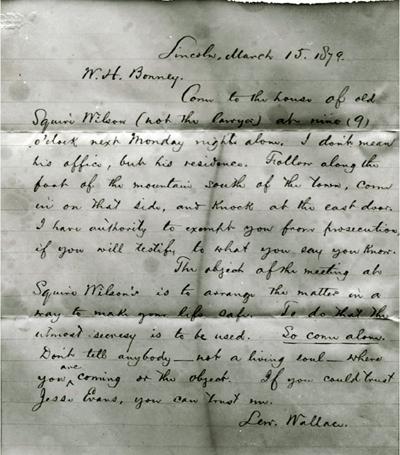

McSween’s death marked the end of the war. In total, twenty-two men had died. At the time, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Civil War general Lew Wallace governor of the New Mexico Territory. Determined to end the bitterness, Wallace offered amnesty to everyone who had fought in the war—except those indicted for murder. Because there was a warrant out for Billy the Kid for the murder of Sheriff Brady, he did not qualify for forgiveness. But Billy, being a bright sort, had a plan. He had witnessed James Dolan and two other men murder a Las Vegas lawyer, Huston Chapman. The Kid was hoping to arrange a deal; he wrote a letter to the new governor, stating that he would agree to testify against those three men in exchange for the same amnesty granted other Regulators. “I was present when Mr. Chapman was murdered,” he wrote. “I know who did it…. If it is in your power to annully [

sic

] those indictments I hope you will do so as to give me a chance to explain…. I have no wish to fight any more indeed I have not raised an arm since your proclamation.”

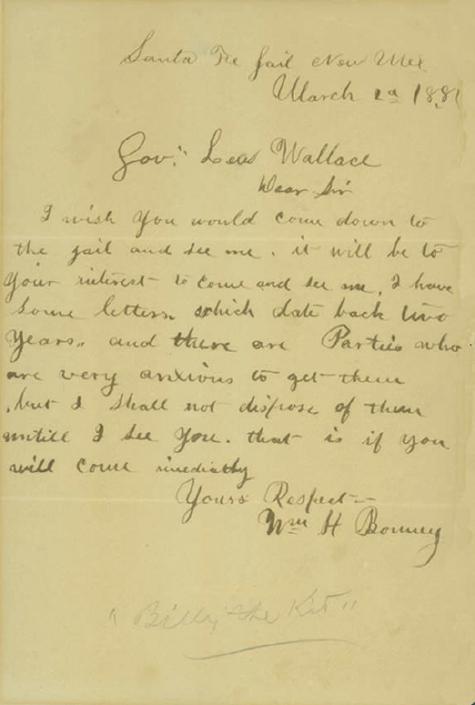

Meeting face-to-face with a feared killer was not out of the question for Governor Wallace. In addition to fighting in the war and trying to bring peace to a violent region, he was writing a novel that would become part of American literary history,

Ben-Hur.

On March 17, 1879, Wallace and Billy the Kid met in the home of a man named John Wilson. Billy carried his pistol in one hand and his Winchester in the other. Wallace agreed to Bonney’s terms, but only if Bonney would submit to a token arrest and stay in jail until his testimony was completed. Billy was leery, supposedly telling Wallace, “There’s no justice for me in the courts of this country. I’ve gone too far,” but agreed to think it over. It was said that Wallace promised that if Bonney gave himself up, the governor would set him “scot free with a pardon in your pocket for all your misdeeds,” but Bonney insisted that rather than his being “captured,” he wanted it reported that he had surrendered. Two days after the meeting, he accepted the deal and surrendered to authorities.

He was held in a makeshift cell in the back of a store. His testimony helped to convict Dolan, but the local district attorney reneged on the deal; rather than letting him go, he decided to bring him to trial for Sheriff Brady’s killing. After three months sitting in his cell and with his own trial for murder now scheduled, Billy did what came naturally—he slipped out. He probably could have found safety and a long life across the border in Mexico, but he’d grown sweet on Pete Maxwell’s younger sister, Paulita, so instead he rode for Fort Sumner, where he believed he could live among his Mexican friends.

Billy the Kid’s unusual correspondence with Governor Lew Wallace led to the wanted fugitive actually meeting face-to-face with the future author of the classic

Ben-Hur.

Billy believed they had worked out a deal that would result in his pardon, but when he was betrayed he escaped from prison and shot his way into legend.

Pat Garrett became famous for supposedly killing Billy the Kid. But his account has long been disputed. Inconsistencies in his story led to him becoming a controversial figure. Although he did not receive the reward money, citizens who felt threatened by the Kid collected the equivalent of twenty thousand dollars for him.

Among the people he surely got to know around Fort Sumner at that time was a former buffalo hunter and cowpuncher by the name of Pat Garrett, who had part ownership of Beaver Smith’s Saloon. Depending on which story you choose to believe, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid either barely knew each other or had become such close friends and gambling buddies that they were called Big Casino and Little Casino.

It is possible that Billy the Kid might have settled down with Pete Maxwell’s comely sister, but the sad truth is that he was in too deep. Although Bonney was a wanted man, it wasn’t a big secret that he had been seen around Fort Sumner. In January 1880, Billy met a man named Joe Grant in a local saloon. They got to drinking, and Grant confided in him that

he aimed to become famous by killing the outlaw Billy the Kid as soon as he could find him. Grant wasn’t the first man to make that boast, but he made the mistake of picking the wrong man to make it to. Billy asked to see his six-shooter, then managed to either empty the shells or set it on an empty cylinder. He handed it back and then admitted that, in fact, he was the very man that Grant was seeking. In some tellings, he then got up and walked out of the saloon. Grant fired at him; his gun clicked on the empty chamber. Billy dispatched him with a single shot. “It was a game for two,” he later explained, “and I got there first.”

To survive, Billy organized his own gang, which became known as “the Rustlers,” or Billy the Kid’s Gang. There was no lack of young men willing to ride with the famous outlaw, among them Tom O’Folliard, Charlie Bowdre, Tom Pickett, and Dirty Dave Rudabaugh. As their name suggests, they rustled cattle and stole horses, just as Billy had done years earlier.

The presence of a famous outlaw who had escaped justice riding the range with impunity finally got the attention of Governor Wallace. In November, he appointed Pat Garrett sheriff of Lincoln County. He might have received that badge because he promised to bring law and order to the county, but many people believed it was because he had been friends with Billy Bonney and knew where he was most likely to be found.

In late November, the gang stole sixteen horses from Padre Polaco and headed out to White Oaks to sell them. On the way they stopped at “Whisky Jim” Greathouse’s ranch and way station and sold him four. Billy the Kid also intended to meet with his lawyer in White Oaks to see if there was any way of making a deal with the government. White Oaks deputy Will Hudgens raised a posse and tracked the fugitives to the Greathouse Ranch. Hudgens sent a note inside, informing the outlaws that they were surrounded and demanding their surrender. Jim Greathouse personally delivered their refusal. Apparently stalling until it got dark enough for them to make their escape, the gang agreed to allow the blacksmith Jimmy Carlyle, who was trusted by both sides, to come inside and discuss the terms of surrender. Greathouse agreed to stay with the posse as a voluntary hostage to ensure Carlyle’s safety.

The Rustlers passed the day drinking. When Carlyle failed to return, the posse threatened to shoot Greathouse. As it grew dark, a member of the posse accidentally fired his weapon. Hearing that shot, Carlyle believed that the posse had shot Greathouse and that therefore his own life was suddenly in great jeopardy. He made a run for it, leaping out of a window into the snow. Billy the Kid later wrote to Governor Wallace to explain what happened that day: “In a short time a shot was fired on the outside and Carlyle thinking Greathouse was killed, jumped through the window, breaking the sash as he went and was killed by his own party they thinking it was me trying to make my escape.” Members of the posse swore that the shots came from inside and specifically blamed the Kid. It made no difference to Carlyle how it happened: Somebody shot him dead.

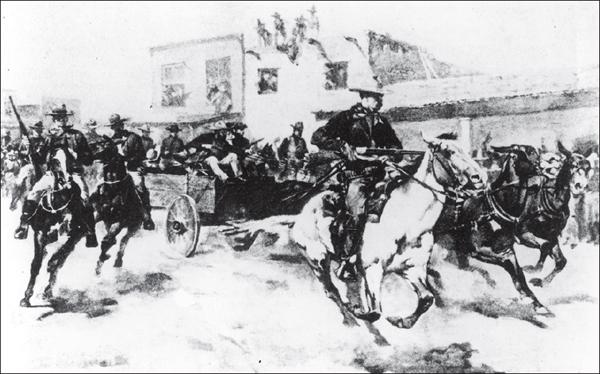

Sheriff Pat Garrett’s posse pursued Billy the Kid for four days before trapping him in Stinking Springs. This 1880 photograph shows the posse arriving in Santa Fe with its captives.

The posse opened up on the house, firing as many as seventy shots without nicking anyone. When night fell, the posse gave up and rode back to White Oaks, allowing the gang to make tracks. Three days later, the Greathouse Ranch burned to the ground. The arsonists were never found.

The killing of Jim Carlyle outraged the public. The

Las Vegas Gazette

railed in an editorial, “the gang is under the leadership of Billy the Kid, a desperate cuss, who is eligible for the post of captain of any crowd, no matter how mean or lawless…. Are the people of San Miguel

County to stand this any longer?” This editorial might well have been the first time the entire nickname “Billy the Kid” was used; until this point he was generally known as simply “the Kid.”

In response, Governor Wallace posted a notice in that paper, announcing, “I will pay $500 reward to any person or persons who will capture William Bonny [

sic

], alias The Kid, and deliver him to any sheriff of New Mexico.”

Sheriff Garrett knew his success in his job would be measured by his ability to bring Billy the Kid to justice. He organized a posse and quickly picked up Bonney’s trail. On December 18, he learned that the gang was coming into Fort Sumner, and he beat them there and lay in wait for them. Around midnight, the posse heard horses coming into town. Tom O’Folliard was riding point. The posse opened fire, hitting O’Folliard, who screamed, “Don’t shoot, I’m killed!” and died minutes later. The gunfire alerted the rest of the gang to the ambush and allowed them to make a getaway.

But the posse stayed on their trail, catching up with them four days later in Stinking Springs. They quietly surrounded the Kid and his men, who were asleep in an abandoned stone building. Just after sunrise, Charlie Bowdre went outside to feed the horses. The posse evidently mistook him for the Kid and shot him down. Then the posse shot a horse, which fell and blocked the only exit, trapping the gang inside without food or water and little ammo. The standoff lasted almost two days, during which Garrett’s men cooked their meals over an open fire and screamed invitations to the gang to join them. At one point, the Kid challenged Garrett to “[c]ome up like a man and give us a fair fight.” When Garrett responded that he didn’t aim to do that, Billy chided him: “That’s what I thought of you, you old long legged son of a bitch.”

Finally, realizing that it was out of options, the gang surrendered. The men were taken to Las Vegas, where a large crowd gathered to see them. As Billy the Kid told a reporter from the

Gazette,

“If it hadn’t been for that dead horse in the doorway I wouldn’t be here today. I would have ridden out on my bay mare and taken my chances…. We could have stayed in that house but they … would have starved us out. I thought it was better to come out and get a good square meal.”