Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (44 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

The Hole-in-the-Wall in the Bighorn Mountains of northern Wyoming, where the Wild Bunch was formed, was a full day’s ride from civilization. Although outlaws were well protected, life was hard there. Each gang was responsible for its own cabins, livestock, and provisions. There was no leader, no structure—and almost no rules. Among the few prohibited acts were murder and stealing another gang’s supplies.

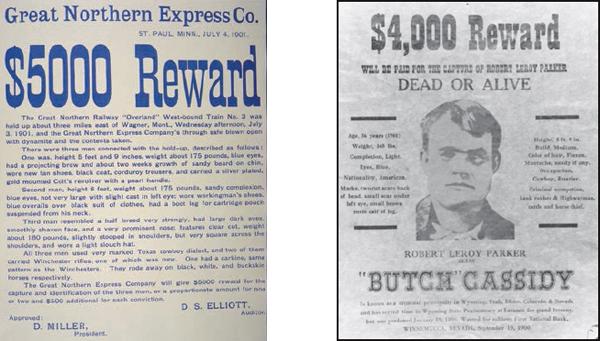

Although the Pinks were successfully dismantling the Wild Bunch man by man, their real target remained the most wanted man in the West, Butch Cassidy. The reward offered for his capture or death was raised to ten thousand dollars. However, the fact that the greatest law-enforcement organization in the world was on his tail didn’t appear to worry him much. On August 29, 1900, a masked robber boarded Union Pacific’s Overland Flyer number 3 outside Tipton, Wyoming, put a pistol to the conductor’s head, and ordered him to stop the train when it reached a campfire by the side of the road. The Wild Bunch had yet to master the art of dynamite and once again blew the baggage car to smithereens, causing a rain of bills estimated at fifty-five thousand dollars. The gang was polite about it, though: After the robbery, a member of the train’s crew complimented the robbers on their courtesy, explaining that one of the holdup men told him the gang really didn’t want to hurt anyone and had made a pact that anyone who killed without reason would be executed. And the bandits said “so long” as they rode away. In a sign of the changing times, a member of the train crew used a pay phone to report the robbery. A posse pursued the Wild Bunch for more than a week, but eventually, as the

Salt Lake Herald

reported, “All hope of capturing the four men who held up, dynamited and robbed the overland express train at Tipton three weeks ago has been given up … the route of the robbers was well chosen and was through a wild and uninhabited country…. The crimes go on record as one of the most successful and daring robberies in the history of the west.”

Less than a month later, members of the gang were credited with looting the First National Bank in Winnemucca, Nevada, of $32,640. These robbers were not as polite, however, threatening to cut the cashier’s throat if he refused to open the safe. Announcing their presence, one robber pulled a pair of .45s and warned, “Stick ’em up, Slim, or I’ll make you look like a naval target,” adding minutes later, “Just feel how fine and soft the atmosphere is above your head, feel it with both hands at once.”

Although it’s impossible to even roughly estimate the total amount of money stolen by the Wild Bunch—because no one knows how many robberies they actually pulled off—without question, they got away with today’s equivalent of millions of dollars. Most of the money was spent on fast living, although stories are told about Cassidy handing out cash to people who needed it or refusing to steal money from civilians. He also was known to be meticulous about paying his debts. A man named John Kelly, who had worked with “Roy Parker” as a ranch hand, once lent him twenty-five dollars, “so he could get out of Butte, Montana.” Several years later, Kelly unexpectedly received a letter from Parker, and when he opened it, one hundred dollars fell out. The enclosed note read, “If you don’t know how I got this, you will soon learn someday.”

After Butch and Sundance stopped the Great Northern Express near Wagner, Montana, in 1901, they cut loose the express car, blew up the safe, and escaped with forty thousand dollars. In those days, different organizations offered rewards—including a percentage of the money recovered—so it’s impossible to know the total amount of the bounty on the heads of the robbers.

It is possible that some of the loot ended up in the hands of women. Butch was a handsome man; his Wanted poster in 1900 described him as five feet nine inches tall with a medium build, a light complexion, flaxen hair, and blue eyes. His face was square and young-looking, and he bore a naturally inviting, bemused smile. When he was imprisoned in Wyoming, in addition to his physical description, his record noted, “Habits of Life: Intemperate.” He appeared to enjoy the company of the ladies as much as they liked being with him, and it was said that he knew how to treat a woman properly.

Sundance was about the same height and weight, but on his Wanted posters, he was said to have “a dark complexion, black hair, black eyes” and “Grecian features.” The Pinkertons added that he was a fast draw who “drinks very little, if any, and is believed to be involved with a school m’arm known only as Etta Place.”

Little is known about Etta Place, not even her real name. Place was the maiden name of Sundance’s mother. And Etta might actually have been “Ethel.” It isn’t even known if she really was a teacher; she also has been described as a saloon girl and as a prostitute who met both Butch and Sundance while working in a brothel, possibly Fannie Porter’s Sporting Parlor in San Antonio. She was about ten years younger than Sundance and had, according to the Pinkertons, “classic good looks … and she appears to be a refined type.” Other people described her as one of the most beautiful women they had ever seen, and men who later knew her in South America said, “She was a goddess—everyone was enamored of her.” Whether Sundance and Etta were legally married isn’t known, but she wore engagement and wedding rings, and they referred to each other as husband and wife.

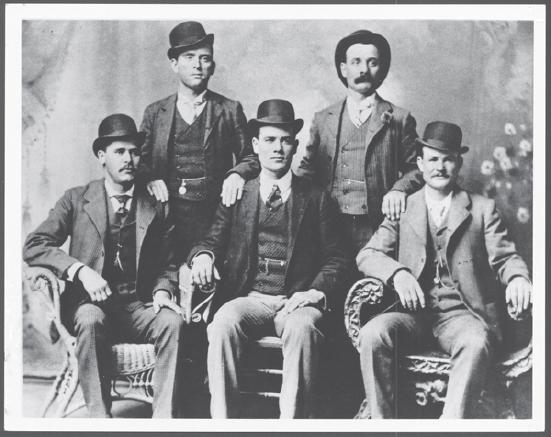

It does seem that the core members of the Wild Bunch truly were friends in addition to being business associates. Less than three months after the Tipton heist, for instance, several members of the gang found themselves living the sporting life in the cattle boomtown of Fort Worth, Texas. For reasons that will never be understood, five members of the gang—Butch and Sundance, Kid Curry, News Carver, and Tall Texan Kilpatrick—walked into the photography shop of John Swartz, dressed in the dandy-wear of bankers and railroad executives, and posed for a formal picture. This iconic photograph eventually became known as “The Ft. Worth Five,” the most famous mug shot in western history.

The proud photographer was so pleased with his work that he enlarged a copy and placed it on an easel in his front window as an advertisement. Among the people who admired the portrait was a Pinkerton agent who happened to be in town on an assignment and immediately recognized the gang. Within days, it was hanging in every post office, train station, Wells Fargo outlet, and law-enforcement office in the country.

Things were beginning to heat up in early 1901 when Cassidy and Sundance decided to make good their final escape. Although they had only done two or three jobs together, they had become close. Life on the run could wear a man down; as gang member Matt Warner once said, “You’ll never know what it means to be hunted. You can never sleep. You’ve always got to listen with one ear and keep one eye open. After awhile, you almost go crazy. No sleep! No sleep! Even when you know you’re perfectly safe, you can’t sleep. Every pissant under your pillow sounds like a posse of sheriffs coming to get you!”

“The Ft. Worth Five,”

Their challenge was to find a place where they weren’t known. After the “Ft. Worth Five” picture had been circulated, no place in America was safe for them—unless they intended to spend the rest of their lives in some forsaken hideout. Fortunately, a lot of Wyoming ranchers were then moving to South America, in particular Argentina and Bolivia, where the weather was good, land was cheap and plentiful, and nobody asked a lot of embarrassing questions. Oh, and the nearest Pinkertons were more than five thousand miles away.

Obviously, they weren’t in a big hurry. After welcoming the New Year 1901 in New Orleans, then traveling by train to Niagara Falls, Butch, Sundance, and the lovely and mysterious Etta Place visited one of the most populous places on earth, New York City. While there, Butch bought a gold watch and Sundance and Etta purchased a lapel watch and stickpin at the fashionable jewelry store Tiffany’s, and the winsome couple posed for a “wedding portrait” at the De Young Photography Studio in Union Square. On the twentieth of January, Mr. and Mrs. Longabaugh, accompanied by her “brother,” “James Ryan,” set sail for Buenos Aires aboard the British steamer

Herminius.

Without their leadership, the remains of the Wild Bunch scattered and by 1905 had passed into Old West history. Historians attribute more than twenty murders to gang members

during its roughly fifteen years in existence. Fifteen members of the gang died with their boots on, and another three committed suicide. Six of them were caught and went to prison—and were killed when they got out. Elzy Lay was believed to be the last survivor. He was pardoned and released from prison in 1906 for saving the warden’s wife and daughter during a prison uprising and lived quietly in Los Angeles until his death—from natural causes—in 1934.

The “wedding portrait” of Harry Longabaugh, the Sundance Kid, and the beautiful Etta Place, taken in New York City in 1901, shortly before they departed for South America

Retirement proved to be only temporary for Butch and Sundance. Upon their arrival in Buenos Aires, Sundance deposited $12,500 in an Argentinean bank. Then the three of them traveled by steamer to Cholila, a small frontier town in the sparsely populated region of Patagonia, where they lived for a time as Mr. and Mrs. Harry “Enrique” Place and James “Santiago” Ryan. Under the terms of an 1884 law, passed to encourage immigration, they were given fifteen thousand acres to develop. A portion of those lands actually belonged to Place, making her the first woman in Argentina to receive land under this law. They built a four-room cabin on the east bank of the Blanco River, with the snowcapped Andes in the distance, and started a ranching operation. It grew to a decent size, according to a letter Cassidy wrote to a friend in Vernal, Utah. The estancia had 300 head of cattle, 1,500 sheep, and 25 horses. Their closest neighbor was almost a day’s ride away.

Sundance and Etta returned to the United States for brief visits in 1902 and again in 1904. During those trips, the tourists visited sites including Coney Island in Brooklyn and the St. Louis World’s Fair, but they also saw several doctors, and the speculation is that both of them were suffering from venereal disease.

The Pinkertons had not let go of their pursuit. By intercepting letters Sundance had written to his family in Pennsylvania, they learned that the bandits were living in Argentina. In 1903, agent Frank Dimaio traveled to Buenos Aires and from there traced them to Cholila. Supposedly the onset of the rainy season prevented him from reaching the ranch, but there is a story that Butch and Sundance killed a Pink sometime that year and buried the body, which, in a quite embarrassing episode, was later dug up by Etta Place’s dog while they were entertaining dinner guests.

Whatever actually took place, it did not appear to alarm the trio, because early in 1904, the territorial governor spent a night as a guest in their cabin, dancing with Etta as Sundance played a samba on his guitar.

Maybe their money was running out, or perhaps they just missed the excitement, but in February 1905, English-speaking bandits later identified as Butch and Sundance held up the

Banco de Tarapaca y Argentina and got away with the modern-day equivalent of about $100,000. Supposedly Etta had assisted in the planning by talking her way into the vault to case the layout of the bank, and later in the actual robbery by dressing in men’s clothing and waiting outside, holding the horses. A story often told in Argentina asserts that she was such a good markswoman that as they made their escape, she was able to split the telegraph wire with a single rifle shot.