Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (20 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

The Lone Ranger became one of America’s most popular characters. In addition to 2,956 radio shows, he was the protagonist of motion pictures and animated features, books, a syndicated comic strip and comic books, 221 half-hour television episodes, and even a video game.

It was a good place for a freeman, because it might have been the most racially and ethnically integrated area in the United States. Few people had the time or the inclination for racism. Everybody pretty much lived together and suffered equally. Even the outlaw gangs were integrated. Dick Glass, for example, who ran one of the most vicious gangs in the

Territory, was himself half-black and half–Creek Indian, and his gang consisted of five black men, four Indians, and two white men.

Bass Reeves was living on his own farm in Van Buren, Arkansas, with his wife, Jinnie, their three children, his mother, and his sister in 1875, when President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Judge Isaac Parker to bring law and order to the Western District of Arkansas. This included all of western Arkansas and the Indian Territory, seventy-four thousand lawless square miles. It was considered a safe place for every type of criminal on the prairie to hide out: the murderers, rapists, cattle robbers, and thieves; the bootleggers selling to the Indians; and the con men. Parker, who was to gain fame as “the Hanging Judge,” was given permission to hire two hundred new deputies. Having heard that Reeves could speak the Indian languages and had often assisted marshals, he offered him a permanent position as a US deputy marshal. Legend has it that when Reeves was asked by a family member why he was willing to risk his life enforcing “white man’s law,” he replied, “Maybe the law ain’t perfect, but it’s the only one we got, and without it we got nuthin’.”

The United States Marshals Service was founded in 1789, created in the Judiciary Act by the First Congress. It was established to be the law-enforcement arm of the federal judicial system. US marshals, and the deputies they legally appointed to assist them, were empowered to serve the subpoenas, summonses, writs, warrants, and other legal documents issued by the

federal courts, make all arrests, and handle prisoners anywhere in the country. Unlike local law enforcement, their jurisdiction was not limited by borders. They were paid for the work they did, meaning they earned a fee for each wanted man they brought to justice. But it was incredibly dangerous work. More than 130 deputies were killed in the Territory before Oklahoma became a state in 1907.

Judge Issac Parker appointed Bass Reeves a deputy US marshal in 1879. In the Hanging Judge’s twenty-one years on the bench, he tried 13,490 cases—and saw seventy-nine people hanged.

Although Reeves was not the first black US deputy marshal, he quickly became the best known, and several of his characteristics would later come to be associated with the Lone Ranger. In those days, when a deputy went out on the trail after outlaws, he would take a wagon (in which to bring back the fugitives he caught), a cook, and a posse man (a deputy who would work with him). Reeves’s posse man was often an Indian from the tribal Lighthorse, which is what the five tribes called their mounted police force. Although Reeves worked with many different Indian officers, apparently there was one man that he chose to ride with whenever possible. His name is lost to history, but he in all probability served as the model for the Lone Ranger’s faithful sidekick, Tonto. Also, later in Reeves’s fabled career, he was known for giving a silver dollar to those people who helped him, which obviously is close to the concept of the Lone Ranger leaving a silver bullet.

Among the many virtues the Lone Ranger shared with Reeves was a great sense of fair play and a desire to bring ’em back alive. Almost immediately after accepting the job, Reeves’s respect for the law became clear. According to legend, one afternoon out on the trail he spotted a group of men holding a lynching party and rode over to them. Lost to history is whether the prisoner was a horse thief or a cattle thief, but apparently he’d been caught dead-to-rights and the penalty for that crime was well known. The suspect was sitting on a horse, his hands tied behind his back, a noose around his neck. When Reeves was told what had happened, he showed the group his badge and explained that in this part of the world, he was the law and he intended to take this man back to Fort Smith. Sitting tall on his own horse, showing his two pistols and complete confidence, he presented a figure nobody seemed anxious to challenge. He cut the noose and rode away with the suspect. As far as he was concerned, that man’s fate needed to be in the hands of Judge Parker, not a mob out on the prairie. Nobody dared try to stop him.

He also believed in bringing prisoners back alive, although he didn’t hesitate to shoot when it became necessary. During a tense confrontation with a horse thief named John Cudgo, he laid out his philosophy. In 1890, Reeves went to Cudgo’s spread on the Seminole Nation to arrest him for larceny. The two men had known each other for almost a decade. As Reeves approached Cudgo’s house, the outlaw suddenly popped out from beneath his front porch, holding his Winchester. Reeves ordered him to surrender and he refused, warning that no marshal was taking him back to Fort Smith—especially not Reeves. He then asked Reeves to send his posse men away so that the two of them might talk. When the men were gone, Cudgo cocked his rifle and said he wanted to be allowed to die in the house he’d built, trying to provoke Reeves into shooting him. Reeves shook his head and told him, “Government law didn’t send me out here to kill people, but to arrest them.” Hours later, Cudgo surrendered without a single shot being fired.

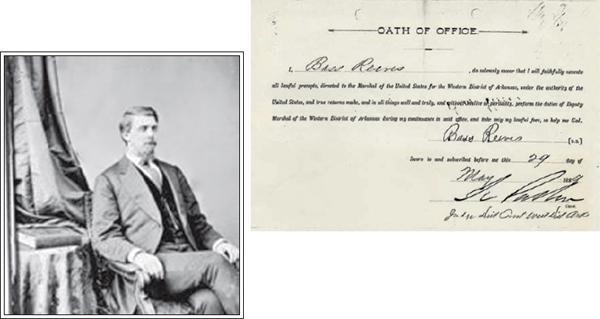

Bass Reeves (

far left

) had served as a deputy marshal for twenty-eight years when this “family photo” was taken in 1907—the year Oklahoma entered the Union and instituted the Jim Crow laws that forced him to end his federal law-enforcement career.

As for his integrity, few tasks could possibly be more difficult for a lawman than having to arrest his own son, and that was the situation Reeves faced in 1902 when his son Bennie was accused of fatally shooting his wife when he caught her cheating on him. After the murder, Bennie Reeves had fled into the Territory. When the district marshal initially gave the warrant to another deputy, Reeves supposedly insisted that he be the man to serve it, explaining, “There’s no sense in nobody else getting hurt over my son. I’ll bring him in.” He tracked Bennie to a small town. Nobody knows what took place between the two of them, but Reeves brought his son to justice. Bennie Reeves was convicted of the crime and sentenced to life imprisonment at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, but was released for good behavior after ten years.

Reeves also arrested his own minister for selling whiskey. Reeves himself served as a deacon of his church in Van Buren, Arkansas, and it was said that some nights while on the trail he would chain captured fugitives to a log and preach the Gospel to them, asking them to confess their sins and repent.

Bass Reeves served as a US deputy marshal for thirty-three years. Although the precise number of men he tracked down and brought to justice isn’t known, he is credited with more than three thousand arrests. The number of men he shot or killed also isn’t known, although newspapers reported that he had killed twenty men. Outlaws used to say that drawing on Bass Reeves was as good as committing suicide. Whatever the number, by the time he retired he had become a legend, and songs were being written about him. It was said that when the famous outlaw Belle Starr heard that Reeves had been given the warrant for her arrest, she actually walked into Fort Smith and surrendered.

Just like the Lone Ranger, Reeves would travel light and move as quickly as possible. Because he couldn’t read the warrants, when getting ready to go out on the trail he would have someone read as many as thirty of them to him. He would memorize each one, including the crime and the description of the wanted man, and was said to have perfect recall. He usually traveled with a wagon driven by his cook, one posse man, and a long chain. He often traveled with two horses; if he had to work in disguise he didn’t want his good riding horse attracting attention. His posse would stay on the trail for several weeks, sometimes months, and the wanted men he captured would be chained to the rear axle of the wagon, usually in pairs, until he’d caught his fill and decided to bring them all back to Judge Parker’s court. Other deputies were bringing in five or six men at a time; on one trip Reeves returned with sixteen

men and collected seven hundred dollars in fines; he always claimed that the largest number he brought in at one time was nineteen horse thieves, for which he was paid nine hundred dollars. On occasion he was also known to pack his bedroll and go out into the wilderness by himself, an image of the lone deputy that easily can be seen as inspiration for the Lone Ranger.

In 1902, Reeves went into the Indian Territory and captured his son, Bennie, who had shot his wife. Ben Reeves served ten years before being released for good behavior.

Among his most famous arrests was the nefarious Seminole To-Sa-Lo-Nah, also known as Greenleaf, who was wanted for the brutal murders of at least seven people, as well as for selling whiskey to the tribes. Four of his victims were Indians who had worked with deputies as posse men to try to capture him—he had shot the last one, in fact, twenty-four times. That made it very difficult to find an Indian tracker who would even speak his name. Greenleaf had successfully eluded capture for eighteen years when Reeves got the warrant for his arrest. Reeves used his own network of informants, men who trusted him to protect them, and one of them got word to him that Greenleaf had recently brought a wagonload of whiskey into the area. In the middle of the night, Reeves and his posse man crawled close enough to the house in which Greenleaf was staying to hear him whooping and shouting. When the house finally grew quiet, Reeves led his posse in an assault, jumping over a fence and getting the drop on the killer before he could go for his gun. After Reeves had put the cuffs on Greenleaf, a steady stream of people came to look at the vicious killer long believed to be uncatchable, now in chains.

Perhaps the Lone Ranger’s most instantly identifiable feature was the black mask he wore to disguise his true identity. Although Reeves didn’t wear a mask, like the fictional character he did sometimes use disguises to help him draw close to dangerous criminals. He was known to impersonate preachers, cowboys, hobos, farmers—whatever seemed suitable for the situation. Once, for example, he was tracking two brothers who had a five-thousand-dollar bounty on their heads. No one had been able to get near them. Knowing that the two men had remained in contact with their mother, Reeves supposedly shot two holes through an old hat, put it on along with ragged clothes and shoes with broken heels, hid his pistol and handcuffs under his clothes—then walked twenty miles to the mother’s home. He arrived there filthy, sweating, and thirsty and pleaded with her for water and a square meal, complaining that he was on the run from a posse. The woman invited him in and permitted him to stay the night, telling him that her two boys were also on the run and suggesting they might work together. After dark the two fugitives snuck into the house. While they were sleeping, Reeves snapped his cuffs on both of them. When he marched them out in the morning, their mother is said to have walked with them for the first several miles, yelling and cursing at Reeves every single step of the way.