Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (24 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Custer’s lovely wife, Libbie, seen here with her husband (seated) and his brother Tom Custer (a two-time Medal of Honor recipient who also perished at Little Bighorn), often traveled with her husband on the frontier.

In the final battle of the Civil War, when Robert E. Lee began his retreat at Appomattox Station, Custer’s division cut off his last route of escape, then captured and secured supplies that Lee’s troops needed desperately. He received the first truce flag from a Confederate force. The newly appointed major general of temporary volunteers was in attendance at the Appomattox Court House when Lee offered his sword in surrender to Grant. In recognition of Custer’s valor, his commander, General Sheridan, purchased the table on which the surrender document was signed and presented it as a gift to Libbie Custer.

George Custer emerged from the Civil War as a national hero, although at the conclusion of hostilities, his temporary promotion to general of the volunteers ended and he was returned to his permanent rank, once again becoming Captain Custer. Beginning with George Washington, America had rewarded victorious military leaders with political office. General U. S. Grant was already on his way to becoming president, and Custer certainly could have moved into business or politics and transformed his fame into a safe and financially secure life. Railroad and mining companies offered him jobs. He might have accepted the offer to become adjutant general of the army of Mexican president Benito Juárez, which would have put him right back in the middle of battle, this time fighting Emperor Maximilian. But the army refused to give him the year’s leave he requested, meaning he would have had to resign his commission if he wanted to fight for Mexican freedom. He considered running for Congress from Michigan but decided against it, telling Libbie that the political world had surprised him. “I dare not write all that goes on underhand,” he said.

When President Andrew Johnson toured the country, trying to build support for his Reconstruction policies, he brought George and Libbie Custer with him, knowing that even those who opposed him would turn out to cheer the Custers. Captain Custer’s admittedly large ego was probably bursting from all the attention. He considered all the offers, but in the end, he was a soldier. He loved the challenges of leadership, he loved being with his men on a campaign, he loved the planning and the execution of strategy, but most of all he loved the taste of battle.

There was only one war left to fight. The Plains Indians were on the warpath.

Since the beginning of American westward expansion, the native tribes had been continuously pushed into smaller and smaller areas. Those tribes that had tried to fight back were eventually defeated, often at great cost. By the end of the Civil War, only a few tribes—the Sioux, Cheyennes, Arapahos, Kiowas, and Comanches—had the will and the resources to fight for their land and their traditions. The army was sent west to subdue those tribes and force them onto reservations.

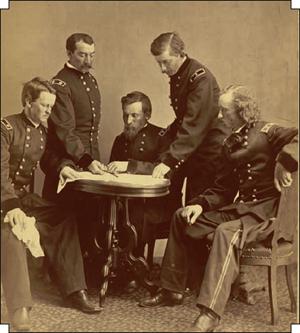

This 1865

Harper’s Weekly

photograph shows General Philip Sheridan (

second from left

) with his generals—Wesley Merritt, George Crook, James William Forsyth, and George Armstrong Custer—around a table examining a document.

When Congress created four cavalry units to fight the Indians on the western frontier, Custer used his political contacts to secure an appointment as lieutenant colonel of the Seventh Cavalry. Obtaining this command had not been easy; while in Washington, he had become involved in a complicated political situation. He had testified in a corruption hearing against the secretary of war, angering President Grant. Generals Sherman and Sheridan had interceded successfully on his behalf, but certainly there was additional pressure on him to bring back some victories. As General William T. Sherman wrote, Custer “came to duty immediately upon being appointed … and is ready and willing now to fight the Indians.”

Custer probably discovered rather quickly that the tactics he had mastered against the Confederacy had little value on the Great Plains. The Civil War had been fought in proper military fashion by two great armies that stood face-to-face and battled until one side was decimated. In that type of warfare, Custer’s chosen strategy of attacking ferociously and hitting the enemy before they were prepared for the fight often proved decisive. But the Indians did not fight static battles. Frequently outnumbered and fighting a better-equipped enemy, they had mastered the art of guerrilla warfare. Rather than fighting as one army with a centralized command structure, they would travel and live in small groups. Rather than trying to take and hold territory, raiding parties would attack isolated targets—wagon trains

or settlers, for example—then disappear. And rather than fighting a pitched battle when attacked, they would fade into the protective hills and forests.

Custer found himself chasing an elusive enemy. By the time he would be notified of an attack, homesteads would already have been burned to the ground, victims slaughtered, and the Indians long gone. Through the summer of 1867, Custer’s Seventh Cavalry was reduced to providing limited security when possible, but mostly chasing ghosts. His biggest enemy turned out to be his own growing frustration and anger.

Any doubts his troops might have begun harboring about his leadership ability were reinforced one day when he spotted a herd of antelope far in the distance. He released the pack of dogs he brought along to track Indians to pursue the herd—and then suddenly took off after them. He rode so fast and so hard that he almost lost sight of his column. He was about to turn back when he saw the first buffalo he had ever laid eyes on and raced toward them. He brought his horse alongside one and ran gloriously at full speed next to this huge animal—and when he finally moved to shoot it with his pistol, the buffalo jostled him, causing him to shoot his own horse in the head. He was thrown into the dirt, but except for some bruises, he was uninjured. Only then did he realize that he was lost and alone on the vast prairie. As he would describe this incident, “How far I had traveled, or in what direction from the column, I was at a loss to know … I had lost all reckoning.”

Once again, Custer was very lucky: Several hours later his men found him—before the Indians did.

The Indians were there; the Seventh Cavalry just couldn’t find them. Instead they kept coming upon the ruins of their attacks. Although Custer had seen many men killed, wounded, and horribly disfigured during the war, this was the first time he had seen evidence of the Indians’ brutality. “I discovered the bodies of the three station-keepers, so mangled and burned as to be barely recognizable as human beings. The Indians have evidently tortured them …” It was determined they had been killed by Sioux and Cheyennes.

Custer pushed his men hard, and they began to resent him for it. They also resented that Seventh Cavalry officers continued to eat well, while their rations included old bread and maggot-infested meat. In the heat of battle, Custer had been able to mold his troops, but in the summer heat of the plains, he was losing control. To maintain discipline he began tightening his rules. After gold was discovered in the region, thirty-five soldiers deserted and set out to seek their fortunes in the mines. In response, Custer issued a harsh and highly controversial order: Catch them and shoot them. He was reported to have said, loudly enough for all his men to hear, “Don’t bring one back alive.”

There were alternative punishments—military regulations also permitted him to whip or tattoo them—but he chose the harshest sentence. Three of those deserters were dealt with according to his orders; two of them died of their wounds. By the middle of the summer, his men were on the verge of mutiny. Frustrated, tired, and lonely, Custer made a rash and inexplicable decision: He took seventy-six men with him and rode to eastern Kansas to be with his wife. He deserted his command, and that mistake was compounded when, during the three-day ride, two of his men were picked off by a band of about twenty-five Indians—and still he kept going. Soon after reuniting with Libbie, he was arrested for being absent without leave and for ordering deserters shot without a trial. His court-martial lasted a month, and only a few officers—including his brother Tom—testified on his behalf. The court found him guilty as charged and suspended him from duty without pay for a year. His fall from the heights had been brutally quick; his once-promising career was shattered.

George Custer had been prepared to deal with pretty much anything—except failure. He had always been able to skirt the rules and get away with it, but not this time. He spent that year trying to rehabilitate his reputation, writing magazine articles detailing his Civil War exploits and justifying the actions for which he had been suspended.

Meanwhile, the Indians grew bolder. During the summer of 1868, for example, they killed 110 settlers, raped thirteen women, and stole more than a thousand head of cattle. General Sheridan was made commander of the Department of Missouri, a huge area encompassing parts of six future states and the Indian Territory. At his request, Custer’s suspension was ended several months early and he was given orders to “march my command in search of the winter hiding places of the hostile Indians, and wherever found to administer such punishment for past deprecations as my force was able to.” He was ordered to “destroy their villages and ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, and bring back the women and children.”

Custer was extremely pleased to be recalled, and he had every intention of fulfilling those orders. He knew his career depended on it. On November 26, 1868, Colonel Custer’s scouts located a large Cheyenne village near the Washita River in what is now Oklahoma. The Indians had camped there for the winter. Fearful that his presence would be discovered, Custer decided not to wait for his scouts to gather intelligence. Instead, he planned his attack. Had he waited, he would have learned that the people in this village had nothing to do with attacks on settlers: This was a peaceful camp located on reservation land, where they had settled after the government guaranteed their safety to the chief Black Kettle. A white flag actually was flying from a large teepee, further evidence that this tribe had given up the fight.

Custer also would have discovered this was simply the westernmost village of a huge

Indian camp stretching more than ten miles along the river. In addition to the estimated 250 people in this village, more than six thousand native people from many tribes had made camp there for the winter.

But even that knowledge might not have discouraged his attack. His determination was so strong that when an aide wondered aloud if there might be more Indians in the camp than was believed, Custer replied firmly, “All I’m afraid of is we won’t find enough. There aren’t enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry.”

Custer’s reputation as an Indian fighter was established in his 1868 attack on a large Cheyenne village on the Washita River, where he first employed the tactics that would doom his troops on the Little Bighorn.

He divided his 720 men into four elements and, at dawn, attacked from four positions. The signal to attack was the unit band striking up the song “Garry Owens.” The unprepared Cheyennes were unable to mount any kind of defense and instead dispersed into the surrounding hills and foliage. The chief, Black Kettle, and his wife were killed in the first moments of the fighting. While Custer later reported killing 103 Cheyennes, that figure is generally accepted to be greatly exaggerated, with the actual number being closer to fifty. But that number included many noncombatants—women and even children. The Seventh Cavalry also took fifty-three hostages, who were put on horses and dispersed among the troops. But in the midst of the battle, several warriors reached their horses and escaped. Major Joel Elliott, Custer’s second in command, took seventeen men and raced downstream in pursuit.

As the battle raged, Custer must have been stunned when he looked up at the top of the rise and saw as many as a thousand warriors “armed and caparisoned in full war costume” looking down upon his force. “[T]his seemed inexplicable,” he wrote later. “Who could these new parties be, and from whence came they?” It was only after the battle that he learned the true size of the camp. However, his desperate strategy had been successful—it would have been impossible for those warriors to attack without risking the lives of the hostages. Custer feigned an advance, and rather than engaging him, the Indians dispersed.