Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (26 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Custer often wore a fringed white buckskin jacket, like this one in the Smithsonian, reportedly so that his troops could easily identify him during a battle.

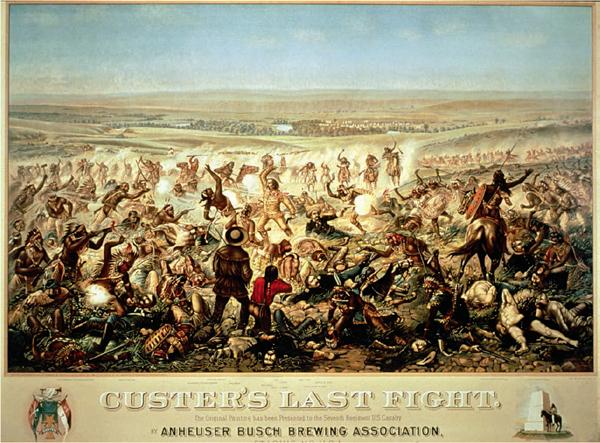

Although the massacre shocked the nation in the midst of its centennial celebration, by 1889, Custer’s heroic last fight was being celebrated in one of the very first beer advertisements, a colored lithograph that hung in saloons throughout the country and helped create the enduring image of the brave soldiers. Many of the details are wrong. The original painting, donated to the Seventh Cavalry, was destroyed in a barracks fire.

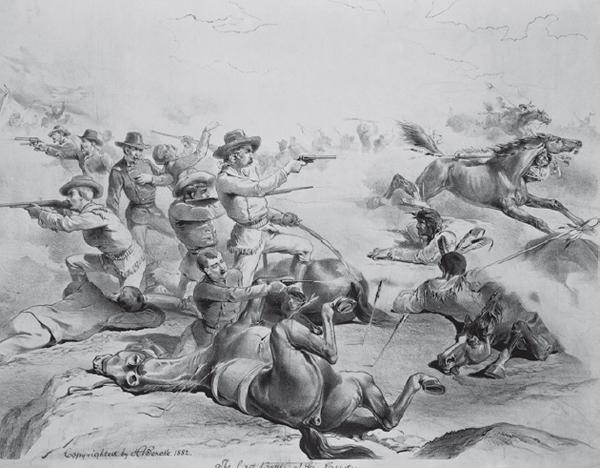

It will never be known whether Custer fully understood Reno’s predicament. But at some point, he must have realized that his only hope of victory lay in taking sufficient hostages to force the warriors to lay down their weapons. When it became apparent that Sioux warriors blocked his path, it was no longer a matter of victory—he was fighting for survival. He retreated up the slope, trying to reach high ground. There was no cover for his troops, so he ordered them to kill their horses to provide some defense. But it was hopeless. His soldiers were rapidly overwhelmed by a massive force attacking with guns, arrows, clubs, and lances. Custer was shot in his breast, and then in his temple, the second shot killing him.

In about twenty minutes, all 225 of Custer’s men were dead. Sitting Bull supposedly once told an interviewer that Custer laughed in the last moment of his life, although that’s doubtful, because evidence indicates that the Indians were not even aware that Custer was among the dead. In addition to George Custer, his brothers Tom and Boston and his nephew Henry Reed died on what has become known as Last Stand Hill. An Associated Press reporter sent to cover Custer’s victory was the first AP reporter to die in combat. His notes were found on his body, concluding, “I go with Custer and will be at the death.”

The nation, celebrating its centennial, was stunned and shaken by the unexpected news of Custer’s Last Stand. It was said that America’s heart was broken. The day after the battle, the Indians packed up their camp and began moving. But this great victory soon proved to be the last major battle of the Indian wars: The defeat caused the army to increase its efforts to subdue the tribes, and within five years, almost all Sioux and Cheyennes would be settled on reservations.

The nation replayed the battle of Little Bighorn for many years, trying to understand how one of its most brilliant leaders had been so brutally slaughtered. Benteen was criticized for reinforcing Reno rather than Custer, and people wondered if the animosity between the two men had played any role in his decision. But, in fact, he had little choice: Reno was his commanding officer and had ordered him to stay. Reno himself was accused of both cowardice and drunkenness at Little Bighorn. He demanded a court of inquiry be convened; while it did not sustain the charges, it also offered no rebuttals to the claims made against him. But as William Taylor, a soldier who served at Little Bighorn under Reno, later wrote bitterly, “Reno proved incompetent and Benteen showed his indifference—I will not use the uglier words that have often been in my mind. Both failed Custer and he had to fight it out alone.”

Painted only six years after the battle, this lithograph already demonstrates the esteem with which the heroic Custer, standing taller than all his men, a pistol in one hand and a sword in the other, was being portrayed.

Did General Custer’s hubris cause him to underestimate his enemy and lead his men into a massacre? Although no one ever questioned George Custer’s bravery, military historians have been critical of Custer’s tactical decisions, from his initial refusal to accept additional men and weapons to his choice to split up his already outnumbered force and attack without sufficient intelligence.

Years earlier, Custer had written, “My every thought was ambitious. I desired to link my name with acts and men, and in such a manner as to be a mark of honor, not only to the present but to future generations.” Although he achieved his aim to be remembered in history, it is not as he had hoped, because the name George Armstrong Custer will always be associated with one of the most devastating defeats in American history.

THE REALITY OF AN “INDIAN SUMMER”

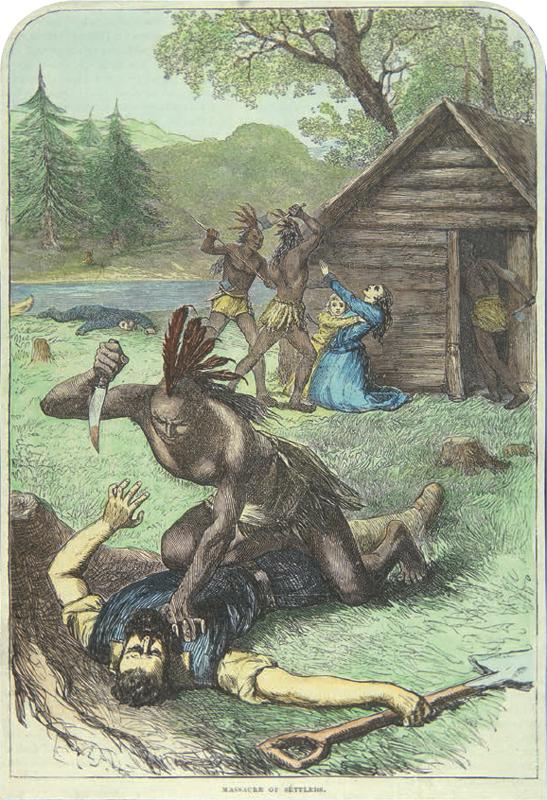

Few things are as welcome as an Indian summer, that sudden and unexpected change in the fall weather after the first frost that brings a brief return to the balmy temperatures of summer. But originally, rather than being welcomed, the possibility of an Indian summer was absolutely

terrifying. In the early days of the West, the fear of Indian raids forced settlers to live together in walled forts from spring through the early fall. At the first frost, the Indians would pack up, leave their villages, and move to their winter camping grounds. When they were gone, the settlers would return to their homesteads and make preparations for the winter. For those settlers, after spending months in crowded, confined surroundings, it was like being released from prison. They actually looked forward to the cold of winter.

Unlike the mood depicted in this pastoral watercolor of Indians camping outside Fort Laramie in about 1860, the early settlers lived in terror of Indian raids.

When the early settlers tried to bring European values to the Native Americans, the Indians resisted. The first recorded Indian attack took place in March 1622, when Powhatans killed 347 men, women, and children in Jamestown in their houses and fields.

But as sometimes happened, the weather would turn once again, bringing back the warm sun to melt the snows—and with it would come the Indians. “Indian summer” meant Indian attack. As Henry Howe wrote, “The melting of the snow saddened every countenance and the general warmth of the sun filled every heart with horror. The apprehension of another visit from the Indians, and being driven back to the detested fort, was painful in the highest degree.”

But as the country grew and the Indians were forced onto reservations, these fears diminished, and over time the term evolved to refer solely to the delightful change in the weather, as it does today.

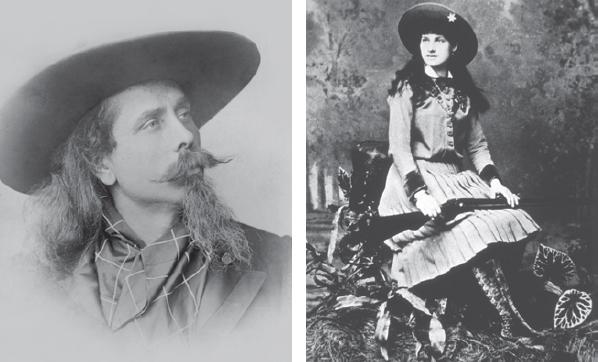

BUFFALO BILL

AND

ANNIE OAKLEY

The Deadwood stage was bouncing over rough terrain, trying to make time. Inside the coach, five very important men were holding on to the straps for dear life. Up on the box, the driver and shotgun were nervously craning their necks, scanning the horizon for any sign of trouble. They’d heard tell that Indians had been seen in these parts and feared an attack. The driver whipped his team, trying to coax a little more speed out of them—and then they heard the first terrible cry.

Indians were closing in fast from both sides, screaming their bloodcurdling war whoops, firing their weapons, and waving their war lances as they raced in for the kill. The driver whipped his team again. The guard turned in his seat and counted six pursuers. He let loose with his first volley, knocking one of the attackers right out of his saddle. The coach was bouncing crazily over the hard ground. “Hold tight,” the driver shouted to his passengers, “and keep your heads down!”

The Indians were shooting back; the driver hunched low in his seat. The guard had reloaded and fired again. A second attacker went sprawling. For a few seconds, the Indians seemed to be closing the gap, but by then the stage was up to full speed, spewing clouds of dust. The driver whipped his horses again and again. With one last

Hey-yaa!

from the driver, the stage pulled away. The Indians pulled up short. One of them angrily stabbed his long lance into the ground, and then they turned and trotted back from where they had come, leaving the banners on the lance ruffling in the wind.

After a few seconds of silence, all twenty thousand people in the audience began cheering. The driver, Buffalo Bill, spun the stagecoach around, creating a dust devil, and brought it to a stop directly in front of the grandstand. He hopped down and opened the door, and the king of Denmark, the king of Belgium, the king of Greece, and the king of Saxony—all in London to celebrate Queen Victoria’s jubilee—climbed out to the loud hurrahs of the audience and waved, and then a mighty roar erupted as the future king, Edward, Prince of Wales, emerged. When the cheering stopped, he said to Bill Cody, in a voice loud enough for all to hear, “Colonel, you never held four kings like these before, have you?”