Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (11 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Unfortunately, when many Utes died from smallpox after receiving blankets from the government’s Indian supervisor, the tribe joined the Apaches on the warpath. Eventually this uprising was smothered, but Carson’s relationship with the tribes of New Mexico never completely recovered. The days when the Indians had freely roamed the plains were ending. During the gold rush, more than a hundred thousand people flocked to the West, and the Indians were pushed off their traditional lands onto reservations. Carson watched this clash of civilizations from his ranch and eventually began to believe that the two peoples could not live together peacefully and that it was best for the Indians to live far away from the white settlers.

In 1868, Carson led a delegation of Utes to Washington, where he negotiated the “Kit Carson Treaty” that guaranteed peace, territory, and government assistance to the tribe.

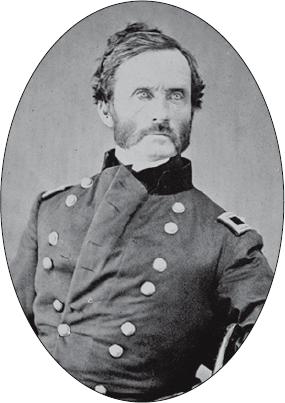

By 1860, the issue of slavery had raised passions in the West, although in that region slaves were mostly Mexican and Indian. While many people in New Mexico sympathized with the Confederacy, Carson remained loyal to the Union. When the Civil War began in 1861, he was appointed a colonel in the First New Mexico Volunteer Infantry. Years earlier, young Kit Carson had walked into the wilderness to live by wit and skill, and finally civilization, or at least the shadow of it, had caught up with him. He moved his family to Albuquerque and went to war.

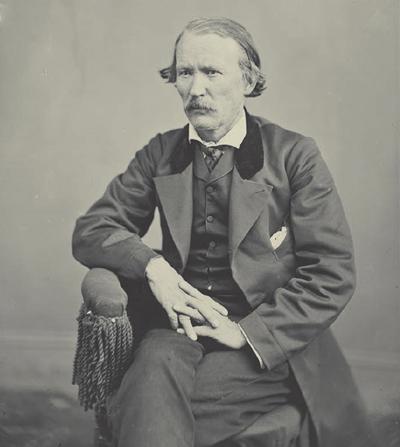

Carson’s first engagement was the 1862 battle of Val Verde, in which both Union and Confederate troops suffered large casualties but neither side declared victory. After two days’ hard fighting, the Union troops withdrew and the Rebels made a wide swing around the garrison at Fort Craig and proceeded up the Rio Grande toward Albuquerque and Santa Fe. After that battle, Kit Carson spent the rest of the war once again fighting Indians. His commanding officer for much of that time, coincidentally, was General James Carleton, the same man who while a major had rescued Carson’s caravan from the Cheyennes. After the Confederate attempt to capture New Mexico had been repulsed, Carleton took aim at the Indian tribes—in particular, the Navajos. Navajo raiding parties had taken advantage of the war to become a serious threat to settlers, a threat that Carleton, who didn’t share Colonel Carson’s respect for the native tribes, was determined to remove.

In 1862, Carleton ordered the Mescalero Apaches moved from their lands in the Sacramento Mountains to newly constructed Fort Sumner and the Bosque Redondo, the Round Forest, on the Pecos River. He issued an order: “All Indian men of that tribe are to be killed whenever and wherever you can find them…. If the Indians send in a flag of truce say to the bearer … that you have been sent to punish them for their treachery and their crimes. That you have no power to make peace, that you are there to kill them wherever you can find them.”

Carson was appalled. He had lived his life with honor, and now he was being forced to choose between disobeying a direct order, which would mean facing a court-martial, and committing despicable acts. No one knows what went on his mind, but he might well have realized that even if he refused the order, the man who replaced him would not—and that man probably would not understand the tribes as he did. While he accepted the command to force the Apaches into confinement, he refused to follow the rest of General Carleton’s orders. Instead he met with the elders of the tribe and convinced them to surrender. Within a few months, he brought four hundred Apaches to Bosque Redondo.

The Mescalero campaign was simply the beginning. Carleton then gave Carson command of two thousand troops and ordered him to capture the Navajos and imprison them on the same reservation as their enemy, the Apaches. “You have deceived us too often,” Carleton warned the Navajos, “and robbed and murdered our people too long, to trust you again at large in your own country. This war shall be pursued against you if it takes years, now that we have begun, until you cease to exist or move. There can be no other talk on the subject.”

During his campaign against the Navajos, Carson’s commanding officer, the brutal general James Carleton, told his troops that Indians “must be whipped and fear us before they will cease killing and robbing the people.”

That was too much for Carson. He resigned his commission, stating, “By serving in the Army, I have proven my devotion to that government which was established by my ancestors…. At present, I feel that my duty as well as happiness directs me to my home and family and trusts that the General will accept my resignation.”

The reason for what happened next will never be known, but the result has caused the name Kit Carson to be reviled by the tribes of the Southwest from that time forward in history. Carleton somehow convinced Carson to change his mind. Some historians believe General Carleton gave him assurances that once the Navajos were on the reservation they would be allowed to live peacefully. It also is true that Carson had come to believe that Indians and settlers could never live peacefully together and urged their separation. He may well have believed that by carrying out this policy he actually was ensuring the safety of both the Native Americans and the new Americans. Whatever the cause, Carson agreed to round up the Navajos.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the Navajos, here crossing Canyon de Chelly in northeastern Arizona, had settled peacefully on this land, as negotiated by Carson.

Rather than standing and fighting the army, the Indians dispersed and fled into the hills. The army retaliated by burning their crops and orchards, their cornfields and bean patches, their fruit trees and melon fields. Guards were posted by sources of salt and water, and Carleton authorized a fee to be paid to soldiers for each Indian animal they captured or killed. The army invaded the Navajos’ main hunting grounds and camp, Canyon de Chelly, and destroyed it, burning it as completely as Sherman would level Atlanta. Without a single major battle being fought, almost ten thousand Navajos surrendered to Carson’s troops. It was the largest number of Indians ever captured, and back east it added to the legend of Kit Carson.

In April 1864, the army led these captives on a forced march of more than three hundred miles to Fort Sumner. Hundreds of Indians died on “the Long Walk,” as it is known in tribal history. Although Carson was not riding with his troops, as their commander he was responsible for their actions. Captives died from sickness, starvation, and exposure to the cold. Some of those who could not keep up were shot by soldiers. When they reached the reservation, conditions were not much better. Many more of the native peoples died during their four years of captivity. Eventually the Apaches escaped and disappeared into the hills, while the Navajos, after signing a treaty in 1868 with General Sherman, were moved to a portion of their traditional lands, where they have remained.

For his service, Kit Carson was promoted to the rank of general.

In late 1864, General Carson was sent to west Texas with 325 soldiers and 75 Ute scouts to subdue the Indians there. Kiowas, Comanches, and Cheyennes were known to be in that area. Carson headed toward the ruins of Adobe Walls, which he remembered from his scouting days two decades earlier. On November 25, his troops attacked a Kiowa village estimated to include 176 lodges. But the scouts failed to discover that this was one of the smallest of many villages in the area. The Kiowas fled from the attack but began gathering a massive Indian force. Within hours, about fourteen hundred warriors attacked. It was similar to the situation in which General Custer would find himself a few months later. One of the men with Carson later described the initial counterattack, writing that the Indians charged “mounted and covered with paint and feathers … charging backwards and forwards … their bodies thrown over the sides of their horses, at a full run, and shooting occasionally under their horses.” Carson’s men dug into the ruins of Adobe Walls. Unlike Custer, Carson had brought with him twin howitzers, big guns, and used them to his advantage. But he was greatly outnumbered. Backfires and the howitzers kept the Indians at a distance until Carson was able to effect a retreat. Carson suffered 6 dead and 125 wounded, while the tribes suffered many times that. Both the army and the tribes declared victory, the Kiowas calling it “the time when the Kiowas repelled Kit Carson.”

When fifty-nine-year-old Kit Carson died in May 1868, he had become among the most famous and respected men in the nation.

At the end of the Civil War, Carson was given command of Fort Garland, in the Colorado Territory. It was the proper choice, wrote General John Pope, because “Carson is the best man in the country to control these Indians and prevent war…. He is personally known and liked by every Indian … no man is so certain to insure it as Kit Carson.”

When he finally left the army in 1867, he resumed fighting to protect the Utes, whom he had long embraced as friends. Although his health was failing, he returned to Washington

with several chiefs to negotiate a fair treaty, which guaranteed to that tribe peace, territory, and assistance. Carson and the Ute chiefs met with President Grant, and eventually a treaty was signed. Then he went home to be with his wife Josefa and their seven children. It was time for him to rest.

He had become one of the most honored men in American history. More than fifty blood-and-thunder novels had been written about him; Herman Melville compared him to Hercules in his novel

Moby-Dick.

He had been instrumental in the creation of an America that would eventually reach from ocean to ocean. But now he was suffering. In 1860, in the San Juan Mountains, he had been leading his horse down a steep hill when the animal slipped and fell on him; Carson became entangled in the lead rope and was dragged for some distance. The internal injuries he suffered caused chest pains, a persistent cough, and breathing difficulty, which plagued him for the rest of his life. In April 1868, Josefa died giving birth to his eighth child. Some believe his spirit died with her. Within weeks he was in bed in the quarters of the assistant surgeon general of the army, just outside Fort Lyon, Colorado. He had been diagnosed with a heart aneurysm, an enlargement of an artery, also believed to have been caused by that fall. As a legendary scout, he knew what lay ahead. Several times coughing attacks threatened his life, and the surgeon, H. R. Tilton, saved it by giving him chloroform. He wrote his will and made arrangements for his children. On May 23, almost exactly one month after his wife’s death, Kit Carson smoked his pipe, ate his favorite meal, and lay down. Late in the afternoon, as the doctor read to him, he suddenly called out, “Doctor, compadre. Adios,” and died.