Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (8 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Crockett became a symbol of the spirit of Texas and America, a man who willingly gave his life for freedom. His last known words, written to his daughter weeks before his death, have often been quoted: “I am rejoiced at my fate. I would rather be in my present situation than be elected to a seat in Congress for life. Do not be uneasy about me, I am with my friends … Farewell, David Crockett.”

His son John Wesley Crockett served two terms in Congress and finally was able to pass an amended version of the land bill that his father had initially introduced. Like so many others, he spent years trying to uncover the facts of his father’s death—but in his lifetime no reliable witnesses stepped forward.

More than one hundred twenty years later, the larger-than-life character Davy Crockett, the King of the Wild Frontier, was introduced to a new generation of young people in a television series—coonskin cap, tall tales, and all—that captivated the nation and had millions of Americans singing his praises, saluting his courage, and romanticizing the frontier way of life.

KIT CARSON

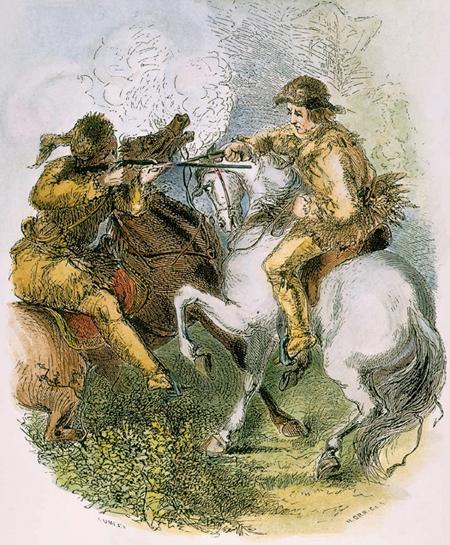

Many years later, in the warmth of his own memories, Kit Carson would describe what happened at the rendezvous in Green River as an “affair of honor.” Although few mountain trappers took much note of the year, Carson put it at the summer of 1835. For those men, who mostly lived in small roaming bands, a rendezvous was an important event. Hundreds of mountain men and natives from local tribes would camp together for a month or, as he wrote in his autobiography, “as long as the money and credit of the trappers last” to trade goods and tales. Coffee, sugar, and flour, then considered luxuries, sold for two dollars a pint, and ordinary blankets for as much as twenty-five dollars apiece. There were daily contests, including shooting, archery, and knife and tomahawk throwing; there was fiddling and dancing; there was drinking and revelry; and, naturally, there was gambling and brawling. The laws of these camps were whatever the strongest men could enforce, and arguments often were settled with rifles at twenty paces. Among the people at this particular meeting on the Green River in Wyoming was an especially disagreeable French Canadian trapper named Joseph Chouinard, who was said to be “exceedingly overbearing” and who, “upon the slightest pretext … was sure to endeavor to involve some of the trappers in a quarrel.” Other trappers avoided him, until one day he violently grabbed a beautiful young Arapaho woman named Singing Grass. Holding tightly on to her arms, he began kissing her and rubbing himself against her.

That was finally enough for Kit Carson. He was small in stature, no more than five feet four, but large in courage. Brandishing his hunting knife, he warned Chouinard to let go of the Indian woman. “I assume the responsibility of ordering you to cease your threats,” he said, “or I will be under the necessity of killing you.”

It was a challenge Chouinard could not turn down. He released the girl and angrily walked off toward his own lodge. Minutes later, the two men faced each other on horseback, as knights had done hundreds of years earlier. The French Canadian carried a rifle; Kit Carson was armed with a single-barrel dragoon pistol. At the mark, they raced toward each other. When they were only a few feet apart, both men fired; Carson’s shot ripped

into Chouinard’s right forearm, throwing off his aim so that, as Carson later recalled, “[H]is ball passed my head, cutting my hair and the powder burning my eye…. During our stay in camp we had no more trouble with the bully Frenchman.”

Kit Carson earned his reputation among mountain men when he stood up to the bully Chouinard at the 1835 rendezvous, as seen in this 1858 woodcut.

As the trappers cheered him, Carson walked off with Singing Grass.

Christopher Carson was born in Madison County, Kentucky, on Christmas Eve 1809, the eleventh of fifteen children. It was the same year Abraham Lincoln was born, the year in which James Madison succeeded Thomas Jefferson as president of the seventeen newly United States. His father was a celebrated hunter and farmer who had fought in the Revolution. Within a year of Kit’s birth, his father moved his family to the frontier settlement of Cooper’s Fort in Boonslick Country, Missouri. This was considered the edge of the civilized nation. Most of the land stretching from there all the way to the Pacific Ocean was wilderness, with occasional settlements inhabited by the native peoples who were fighting to protect their territory, their food sources, and their way of life. It took great skill and daunting courage to survive in these dangerous lands. Those who took the risk were the mountain men, the trappers, the explorers, and the soldiers who went into the unknown in search of adventure. As the author Henry Howe wrote in his classic volume

The Great West

more than one hundred fifty years ago, “From the Mississippi to the mouth of the Colorado, from the frozen regions of the North to Gila in Mexico, the beaver trapper has set his traps in every stream. Most of this country, but for their daring enterprise, would be, even now, a terra incognita to geographers…. These alone are the hardy pioneers who braved the way for the settlement of the western country.”

Carson was loosely related to the legendary frontiersman and trailblazer Daniel Boone—Boone’s daughter was married to Carson’s uncle—and there is no doubt that Boone served as young Kit Carson’s role model. Missouri had been part of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase—bought for about four cents an acre—and quickly became the jumping-off place for expeditions going west, where life was a constant battle for survival against nature—and the native tribes. Carson became a man in that wilderness, learning how to track and shoot and, when necessary, fight Indians.

Carson’s father died when Kit was only nine years old; some histories report that he was killed by Indians, while others claim that a large branch from a burning tree fell on him. His mother remarried, but Kit never got along with his stepfather. When he was fourteen years old, his stepfather apprenticed him to a harness and saddle maker named David Workman, during which time Kit heard the exciting stories told by mountain men returning from the West, stories that captured his imagination. After his second year, he couldn’t wait any longer. “[B]eing anxious to travel for the purpose of seeing different countries,” he ran away, joining a

wagon-train expedition to the Rocky Mountains. Workman placed a notice in the newspaper, offering a one-cent reward for the return of his apprentice.

During the next years, Carson tasted adventure, working as a cook for trapper and fur trader Ewing Young, as a teamster in the copper mines near Rio Gila, and as an interpreter along the Chihuahua Trail into Mexico. He’d dropped out of school before learning to read or write, but he learned to speak Spanish and eight Indian languages from a mountaineer named Kincard. He trapped beaver, traded furs, and, when it became necessary, fought Indians.

His first recorded battle with Indians came in 1829, when one of Ewing Young’s trading parties was attacked by Navajos. Young was determined to get vengeance and organized his own raiding party, which trailed the Indians to the head of the Salt River and waited. When the Navajos spotted a small band of trappers, they attacked—and rode into Young’s ambush. His men—young Kit Carson among them—opened fire and killed fifteen Indians.

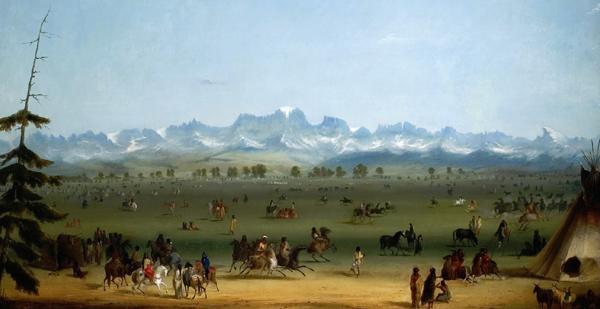

A rendezvous near Green River, Oregon, about 1835

Eventually Carson would become one of history’s most renowned Indian fighters, but he acquired this reputation only out of necessity. The mountain men lived by a warrior’s code that required an eye for an eye, a scalp for a scalp. When one member of your tribe was killed, that score had to be settled. A warrior who showed great courage in battle, who got close enough to physically touch his enemy, was said to be “counting coup,” and this was the highest honor he could achieve. Carson recounted one story in which he was awakened by a Blackfoot brave counting coup—literally prodding him with a knife. The band of Indians had snuck into camp to steal horses. Carson kicked him away, scrambled to his feet while grabbing his own knife, and fatally stabbed his attacker.

In 1839, Carson led a party of forty-three mountaineers in an attack on the Blackfeet who had been raiding their camp. They charged into the Blackfeet village, quickly killing ten warriors. The battle raged for more than three hours. During the action, a mountaineer named Cotton was trapped beneath his horse after it was shot from underneath him. Six warriors raced forward to take his scalp. Carson leaped from his saddle, steadied his hand,

and shot the leader through his heart. Three more Indians were shot down by other shooters before they could reach cover, enabling Cotton to get loose and make his way to safety.

Kit Carson believed totally in the warrior’s code—but he also spent many years living peacefully among the tribes. After his encounter with Chouinard, he took Singing Grass as his wife and settled in her village. When Singing Grass died giving birth to their second child, he married a Cheyenne maiden named Making-Out-Road. He was considered an honored guest in the lodges of the Arapahos, Cheyennes, Kiowas, and Comanches. Even his favorite horse was proudly named Apache. He lived so easily among the tribes that he once remembered, “For many consecutive years I never slept under the roof of a house or gazed upon the face of a white woman…. My rifle furnished nearly every particle of food on which I lived.”

Carson had earned a fine reputation as a hunter and trapper, becoming known as “the Monarch of the Prairies” and “the Nestor of the Rocky Mountains,” Nestor being a mythical Greek king known for his bravery. His word was said to be “as sure as the sun comin’up,” and his skills enabled him to hire on in the 1840s as “hunter to the fort,” meaning he was responsible for supplying all the food for the forty-man garrison at Bent’s Fort, the only trading post on the Santa Fe Trail between Missouri and Mexico. Ultimately, though, Carson and his fellow trappers proved so proficient at their trade that by the time of the last rendezvous in 1840, the beaver had been hunted almost to extinction.

Yet during his years on the frontier, as Charles Burdett wrote in his

Life of Kit Carson,

“his curiosity, as well as care to preserve the knowledge for future use, led him to note in memory every feature of the wild landscape, its mountain chains, its desert prairies …” and prepared him to play a very special role in the settling of the West.

The concept of Manifest Destiny, the dream of a nation that stretched across the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific, was beginning to take hold. At his inauguration in 1845, President James K. Polk prophesized, “It is confidently believed that our system may be safely extended to the utmost bounds of our territorial limits, and that as it shall be extended the bonds of our union, so far from being weakened, will become stronger …”

Kit Carson proved to be extraordinarily important in the fulfillment of that dream. In 1842, after sixteen years on the frontier, he brought his four-year-old daughter, Adaline, to live with his sister in St. Louis, where she could receive the proper education he never had. From St. Louis he boarded the first steamboat at work on the great Missouri River, intending to return to his family homestead. Also on that boat was Lieutenant John C. Frémont of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, who coincidentally was looking to hire an experienced guide to lead him to Wyoming, where he was to survey the South Pass, the most popular route across the Continental Divide, and measure the height of the mountains. After introducing himself to Frémont, Carson explained, “I have been some time in the mountains and I think I can guide you to any point there you wish to reach.” After making inquiries, Frémont hired Carson to guide the expedition at a salary of one hundred dollars a month.