Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (6 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Crockett won his first election, receiving more than twice as many votes as his rival. Although other members of the legislature referred to him derisively as “the Gentleman from the Cane”—meaning from the uncivilized backwoods—he stood up to the wealthy and powerful. His staunch support for the struggling west Tennessee farmers and local folk made him so popular that a year after his election his constituents presented him with a .40-caliber flintlock with the motto

go ahead

inscribed in silver near the sight. He named this beautiful hunting rifle Old Betsy, in honor of his oldest sister.

When he was not doing the people’s work, he was building a new cabin for his family in the wilds of the Obion River, relying on Old Betsy to keep his family fed and warm. On one hunt, he brought down a six-hundred-pound bear, although he admitted that it took three shots. That he chose to live in the wilderness, where a man survived by his wits rather than his wallet, reinforced his growing reputation as a man of the people. Although he did not intend to stand for reelection in 1823, when a newspaper article appeared to lampoon him, he changed his mind. His opponent, Dr. William Butler, was Andrew Jackson’s nephew-in-law. It proved to be one of the most memorable populist campaigns ever run. On the stump, Crockett confessed that his campaign was financed by the raccoon pelts and wolf scalps his children and hunting dogs had gathered, and he reckoned after visiting Dr. Butler’s impressive home that he walked on fancier materials on his floor than most people’s wives wore on their backs. Crockett wore his buckskin shirt with extra-large pockets—for a twist of tobacky and a bottle of hooch—and won the election by 247 votes.

At this same time, Andrew Jackson’s political fortunes were skyrocketing. The military

hero, who had defeated the British in the Battle of New Orleans and led the nation to victory in both the War of 1812 and the First Seminole War, was a nominee for the presidency in 1824. Although Jackson won the popular vote, the close election was thrown into the House of Representatives, which chose John Quincy Adams. But Tennessee senator Jackson had established himself as a formidable politician and kept his sights firmly on the White House.

Crockett had aroused Jackson’s anger by supporting the candidate running against Old Hickory’s handpicked choice for governor in 1821, personally defeating his relation two years later, and backing Jackson’s opponent when he ran for the Senate. In fact, Crockett called his vote against Jackson “the best vote I ever gave.”

When his supporters urged him to run for Congress in 1825, Crockett accepted their nomination, then lost a woefully underfinanced campaign to the incumbent by 267 votes. But his reputation continued to grow, and it was known that in the winter of 1826, he and his hunting buddies accounted for 105 dead bears. Supposedly he had killed 47 of them himself.

Crockett lived a life of adventure—but one fraught with danger. He almost died twice from malaria, suffered near-fatal hypothermia, and was mauled by a bear. He had cheated death so often that his family refused to believe he had been killed at the Alamo and sent young John Crockett to verify it. Once, while he was earning his living cutting and selling barrel staves, his barge got caught in the rapids and he was trapped in its tiny cabin as it flooded. He struggled to escape through a small window and got stuck, urging rescuers to pull him out no matter what it required, “neck or nothing, come out or sink.” Indeed, they got him out, but he suffered serious injuries. Among the rescuers was a wealthy businessman and politician, Memphis mayor Marcus Brutus Winchester, who would take to Crockett and financially support his successful run for Congress in 1827.

Crockett’s homespun appeal attracted considerable attention in Washington, even before he arrived there. He was introduced by letter to Henry Clay, “the Great Compromiser,” who was preparing to run for the presidency, by Clay’s son-in-law, James Irwin, as an uncouth, loud talker, who was “independent and fearless and has a popularity at home that is unaccountable.”

Even nearly two centuries ago, a backwoodsman who often dressed in hand-sewn buckskin was considered out of place in the nation’s increasingly sophisticated and dignified capital. However, that worked in Crockett’s favor politically. Although he belonged to no political party, the Whigs saw great potential in him and helped build on the myths about him that were already spreading. More than a century later, Crockett would be celebrated on television by the Disney company as a man who wrestled alligators and “kilt him a bear when he was only three,” but the foundations of his legend were laid not in Hollywood but while he was in Congress.

In Congress, Crockett never wavered from his support for the rights of the poor. During his first term, he opposed a land bill because it might result in squatters being driven off their farms, pointing out, “The rich require but little legislation. We should at least occasionally legislate for the poor.” Although he had ended up supporting Andrew Jackson in Old Hickory’s victorious run for the White House in 1828, he didn’t hesitate to fight hard against him—as well as other members of the Tennessee delegation—when the land bill again was proposed in 1830. He answered to a higher power than Washington politicians, he explained: the people who put him in office; the kind of people whose children “never saw the inside of a college, and never are likely to do so.”

Crockett was becoming a problem for Jackson. He was an extraordinarily popular

politician who too often opposed him. Their biggest fight came when Jackson introduced the Indian Removal Act in 1829, which proposed granting to the tribes the unsettled lands west of the Mississippi River, where they would be taught “the arts of civilization,” in exchange for their land within existing state borders. Jackson believed this separation of whites and Indians was the only way to ensure peace and was the most humane way of dealing with the Indian problem. Crockett opposed him; he had lived among Indians his whole life and believed they should be left in peace on their own lands. Describing it as “a wicked, unjust measure,” he voted against it and said bitterly, “I gave a good honest vote, and one that I believe will not make me ashamed on the day of judgment.” The bill passed, but the Cherokee chief sent a letter to Crockett thanking him for his vote.

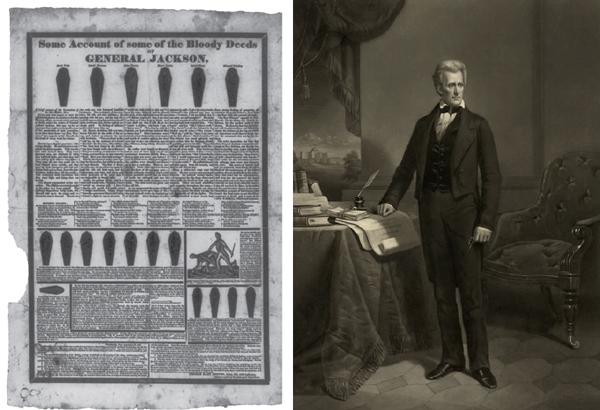

Crockett’s biggest political rival was Andrew Jackson, seen in this 1860 portrait by D. M. Carter, who was charged with extraordinary “bloody deeds” in this 1828 “coffin” handbill.

When Crockett stood for reelection in 1831, Jackson personally recruited a man named William Fitzgerald to run against him. It was going to be a difficult campaign for Crockett because the majority of people in his district had supported the Removal Act. Fitzgerald ran a dirty campaign, accusing Crockett of being a violent drunk and a gambling man who cheated on his wife. His men would post signs advertising a Crockett appearance that Crockett knew nothing about—but when he failed to show up, he was the one who was blamed. The tensest moment of the campaign came during a debate in Nashville. As the

Nashville Banner

reported,

Fitzgerald spoke first. Upon mounting the stand he was noticed to lay something on the pine table in front of him, wrapped in his handkerchief.

He commenced his speech…. When Fitzgerald reached the objectionable point, Crockett arose from his seat in the audience and advanced toward the stand. When he was within three or four feet of it, Fitzgerald suddenly removed a pistol from his handkerchief and, covering Colonel Crockett’s breast, warned him that a step further and he would fire.

Crockett hesitated a second, turned around and resumed his seat.

The episode caused a stir, but Jackson was well liked in Tennessee, and Crockett lost the election. To pay off all his campaign debts, he had to sell his land, and with the assistance of someone who knew how to spell, a man named Matthew St. Clair Clarke, he “wrote”

The Life and Adventures of Colonel David Crockett of West Tennessee,

one of the first campaign biographies. It marked the beginning of his transformation from David Crockett to Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier. It described his life-threatening adventures and his good character while vilifying Andrew Jackson—and was an immediate success. Two years

later, after he defeated Fitzgerald to regain his seat in Congress, his official autobiography was published—partially to correct some of the taller tales told in that first book—and caused such a great stir that a segment of Whigs began suggesting he would be the perfect candidate to succeed Jackson in the White House.

Ironically, considering his feelings about Jackson—in 1833 he told reporters, “Look at my neck and you will not find any collar with a label, ‘My Dog, Andrew Jackson’”—he actually helped the president survive the first presidential assassination attempt in American history. On the afternoon of January 30, 1835, an unemployed house painter named Richard Lawrence, who believed he was King Richard III, approached Jackson as he left the capitol, drew his pistol and, at point-blank range, pulled the trigger. Incredibly luckily for the president, the gun misfired. The sixty-seven-year-old Jackson began hitting his attacker with his cane. Crockett and several other men leaped on Lawrence and dragged him to the ground. In the melee, the madman managed to pull a second pistol from under his coat and fire at Jackson from inches away—and that gun also misfired! Thanks to Crockett, several other men, and amazing good fortune, the president’s life was saved—although no one ever has been able to figure out why either gun, much less both of them, misfired. Lawrence spent the rest of his life in an asylum.

To reinforce his growing reputation, Crockett “authored” another book,

A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett, written by Himself,

and for the only time in his life visited the Northeast, on what arguably was one of the first celebrity publicity tours. He traveled from Baltimore to Philadelphia by steamboat and train, the first time he had ridden on the latter. The Whigs had gathered a large, enthusiastic crowd to greet him when he arrived in Philadelphia, which he described as “the whole face of the earth covered with people.” From there he went to New York, where, once again, delighted crowds turned out to see him. He spent an evening at the theater and toured the roughest area of the city, a pro-Jackson slum known as Five Points. It was so filthy, he remarked, that the people there were “too mean to swab hell’s kitchen,” a phrase that later coined the nickname for an uptown slum. When he reached Boston, again the welcoming crowds turned out, and he toured Faneuil Hall and visited various factories. He dined at the leading restaurants and sipped champagne “foaming up as if you were supping fog out of speaking trumpets.”

Although his congressional district had been gerrymandered by the pro-Jackson legislature in 1833, he had still managed to win that election. But the frontier was moving westward, and Tennessee was being settled by people who didn’t know Crockett and instead were vocal in their admiration for President Jackson. In the congressional election of 1835,

Crockett’s opponent, Adam Huntsman, who had lost a leg in the Creek War, made Crockett’s inability to get a land bill passed by Congress in three terms a major issue in the campaign. Huntsman was supported by both President Jackson and Tennessee’s Governor Carroll and beat Crockett by 230 votes.

During the campaign, Crockett had promised several times to move to Texas if he was defeated or if Jackson’s vice president, Martin van Buren, was elected president. What probably surprised everyone was that this was a campaign promise Crockett intended to keep. On November 1, 1835, dressed in his hunting suit and wearing a coonskin cap, he gave Old Betsy to his son John Wesley Crockett and, following the trail blazed by his friend Sam Houston, set out for Texas with three friends, telling his constituents, “Since you have chosen to elect a man with a timber toe to succeed me, you may all go to hell and I will go to Texas.”

Many have speculated on the real reasons he went to Texas.

Texas

is an Indian word, meaning “friends,” but for hundreds of years it had been unsettled by whites. The territory had been claimed by France and Spain, then became Mexico’s when it won its independence from Spain in 1821. The Mexican government initially had welcomed American settlers to the territory, believing they would control the Indians living there. But by 1826, the Anglos wanted to rid themselves of Mexican control and establish an independent state that they intended to name Fredonia. The leader of the original settlers, Stephen Austin, went to Mexico City to petition for recognition as a separate Mexican state, with the right to form its own legislature. Instead, he was arrested and thrown into a dungeon.

But the spirit of independence had caught hold. In 1835, seventeen thousand of the twenty thousand people living in Texas were Americans. Austin returned to Texas after spending eight months in prison and immediately began forming militias to fight for Anglo rights under the Mexican constitution. Mexican leader Santa Anna threatened an invasion to quell the uprising. The Texas War for Independence began at the battle of Gonzales in October 1835. A month later, Texas declared its independence, naming Sam Houston its commander in chief. It was a situation ripe for heroics.