Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (2 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

And yet he was accused of treason—betraying his country—the most foul of all crimes at the time. What really happened to bring him to that courtroom? And was the verdict reached there correct?

Daniel Boone was born in Pennsylvania in 1734, the sixth child of Quakers Sarah and Squire Boone. His father had come to America from England in 1713. The Boones were known as thrifty, prosperous people. His cousin, James Boone, had a knack for numbers and eventually became known as “Boone, the Mathematician.” But Daniel Boone did not find comfort in the classroom or with books. He had enough schooling to know how to sign his name, but his real education was learning the skills of survival on the frontier: He became an expert hunter, tracker, trapper, marksman, and trailblazer. It was said that no Indian could aim his rifle, find his way through a pathless forest, or search out game better than young Daniel Boone. He was hard to pin down to any one place; he always loved being on his own, away from the clatter of the cities.

Born in 1734 in Birdsboro, Pennsylvania, Daniel Boone was the seventh of twelve children.

When Squire Boone was “disowned” by the Quaker meeting for allowing his children to “marry out of unity”—meaning to marry non-Quakers—he moved his family to North Carolina. The Boones had only just settled there when the French and Indian War began in 1754. Young Daniel Boone served as a wagoneer in British major Edward Dobb’s North Carolina militia. He marched with Lieutenant Colonel George Washington under the despised General Braddock in his disastrous effort to capture Fort Duquesne. When Braddock was killed in the Battle of the Wilderness, Washington took command and began building his heroic reputation. During the war, Boone first heard tell of a place the Indians called the Dark and Bloody Ground, a paradise that some people called Kentucke. An Indian trader named John Finlay had actually been there and was determined to get back. At that time, very little about the lands south of the Ohio River was known to the British, and Boone listened to these stories with excitement, his heart making the decision that he would go there.

A small group of extraordinarily courageous men risked their lives exploring and settling the American frontier. They were people who felt an urgent pull to see what lay beyond the next mountain and depended on their skills, wits, and sometimes just plain luck to reach the next summit. They were most at home in foreign and wild places, living off God’s bounty. Many of these early American pioneers are forgotten, but through hundreds of years of American history, Daniel Boone has stood for them all.

It took Boone twelve more years to finally get to Kentucke, and by that time he had married his neighbor’s daughter, Rebecca Bryan, and they’d had four children, in addition to taking in several nieces and nephews. He’d also explored the area called Florida (he reportedly bought land near Pensacola but elected not to settle there), as well as the unspoiled wilderness of the Alleghenies, the Cumberlands, and the Shenandoah Valley. In 1851, author Henry Howe described Boone’s arrival in Kentucke, writing that his party, “after a long and fatiguing march, over a mountainous and pathless wilderness, arrived on the Red River. Here, from the top of an eminence, Boone and his companions first beheld a distant view of the beautiful lands of Kentucky. The plains and forests abounded with wild beasts of every kind;

deer and elk were common; the buffalo were seen in herds and the plains covered with the richest verdure … this newly discovered Paradise of the West.” Daniel Boone was the first settler to set his eyes and bestow a name on many of the now familiar features of Kentucky. Like many frontiersmen of the time, as Boone explored, he carved his name into the trees to show he had been there, and a beech tree on the Watauga River in Tennessee still bears the inscription

D. BOON CILLED A. BAR ON TREE IN THE YEAR

1760.

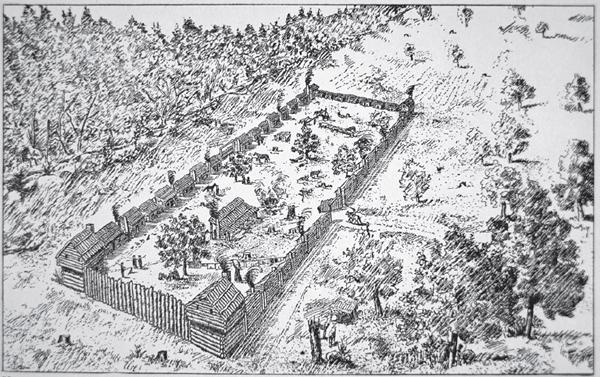

Thomas Cole’s

Daniel Boone Sitting at the Door of His Cabin on the Great Osage Lake, Kentucky,

1826

His first time in Kentucke, he stayed only long enough to know that he’d found the open spaces in which he wanted to raise his family. He returned in 1769 with five other men, blazing the first trail from North Carolina into eastern Tennessee. During that expedition, he spent two years there, twice being captured by Indians; the first time, he was set free, the next time, he escaped. As he later wrote, the Indians “had kept us in confinement seven days, treating us with common savage usage … in the dead of the night, as we lay in a thick cane-break by a large fire, when sleep had locked up their senses, my situation not disposing me for rest, I touched my companion, and gentle awoke him. We improved this favorable opportunity, and departed, leaving them to take their rest, and speedily directed our course towards our old camp.” His companion was his brother-in-law, John Stewart, who had been captured with him both times, but eventually Stewart’s luck ran out. While out hunting one day, he was shot by an Indian raiding party and took refuge in a hollowed-out tree, where he bled to death; his body was found there almost five years later.

Boone would spend his winters hunting beaver and otter, and in the spring sell or trade the furs he had collected. In the summers he would farm and hunt deer, gathering meat for the winter and deerskins for trade. The value of these deerskins, or buckskins, fluctuated against the British pound and later the American dollar, and eventually

buck

became an acceptable slang term for “dollar.”

Boone also made his clothes from the skins of the animals, and his buckskin shirt and leggings, moccasins, and beaver cap were the accepted dress of the frontiersmen.

In 1773, Boone decided it was time to move his family to Kentucke. He sold his farm and all his possessions and agreed to lead the first group of about fifty British colonists into the new territory. On the journey west, his son James trailed behind, bringing cattle and supplies to the settlements. On October 9, James Boone’s small group was camped along Wallen Creek when Indians attacked. They had failed to take the necessary precautions and were defenseless. James and several others were brutally tortured and killed. Although Boone urged the rest of the settlers to push forward, this deadly attack frightened them into returning to civilization in Virginia and Carolina. He had no choice but to go back with them.

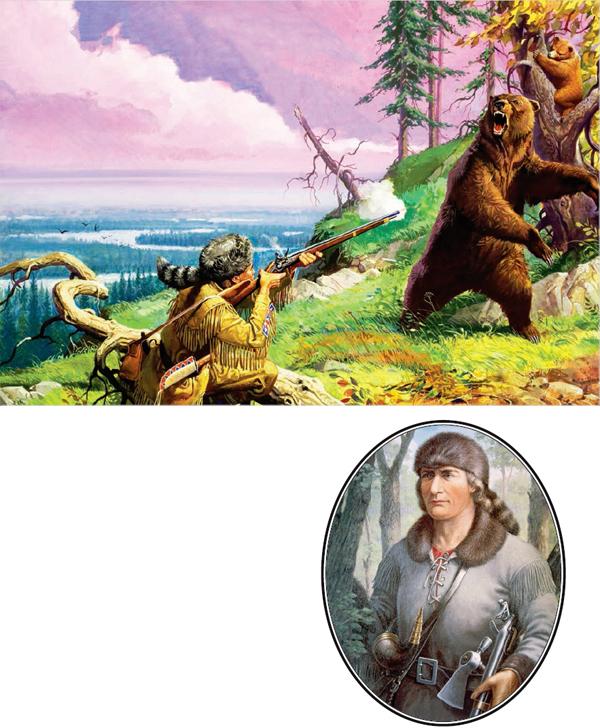

Early American history has been told—and often exaggerated—by the pen and the paintbrush. Daniel Boone’s fame as a bear hunter is depicted by Severino Baraldi (

above

), while this portrait of the lone woodsman was painted by Robert Lindneux.

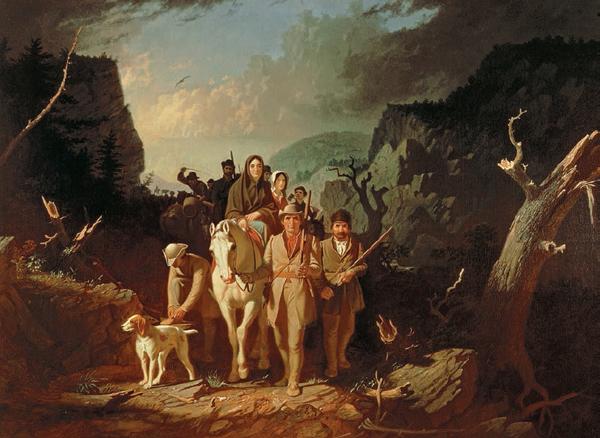

Boone blazing the trail west in George Caleb Bingham’s 1851–52 oil painting,

Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap

Boone was not a man who relished a fight, but he never backed away from one, either. In 1774, he led the defense of three forts along Virginia’s Clinch River from Shawnee attacks and, as a result, earned a promotion to captain in the militia—as well as the respect of his men. While Boone proved to be one of the settlers’ most ferocious fighters, he did understand the reason for the Indians’ resistance and perhaps even sympathized with them, admitting that the war against them was intended to “dispossess them of their desirable habitations”—in simpler words, take their land.

His reputation was growing, the word spread by his admirers, who never hesitated to tell stories of his courage, even if some were a bit exaggerated. In 1775, the Transylvania Company, which had purchased from the Cherokees all the land lying between the Cumberland Mountains, the Cumberland River, and the Kentucky River, south of the Ohio, hired Boone

to lead the expedition of axmen that carved the three-hundred-mile-long Wilderness Road through three states and the Cumberland Gap. It was this trail that opened up the frontier to the many thousands of settlers who would follow.

When Boone’s men finally reached Kentucke, he laid out the town and fort of Boonesborough. During that journey, four men were killed and five were wounded by the increasingly hostile Shawnees. But Boonesborough and Harrodsburg, wrote Henry Howe, “became the nucleus and support of emigration and settlement in Kentucky.” The settlers, including Boone’s wife and their children, raced to erect fortifications strong enough to resist Indian attacks, and on May 23, 1776, the Shawnees attacked Boonesborough. They were repelled, but they would come back, and everybody knew it.

Less than two weeks later, the Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, signed the Declaration of Independence. It would take more than a month for the settlers to learn of it.

The coming war for independence did not really affect or concern them; they were already too busy fighting a war for their own survival. Boone was not a political man and did not strongly support either the Revolutionaries or the British. That was not a luxury he had time for. Life on the frontier was always a daily life-or-death struggle. Just about a week after the noble document was signed, for example, Boone’s daughter, Jemima, and two other young girls were kidnapped by a Shawnee-Cherokee raiding party. He immediately gathered nine men and set off after them.