Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (5 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Davy Crockett, who lives in American legend as “the King of the Wild Frontier,” was celebrated during his lifetime as “the Coonskin Congressman,” a backwoodsman who had “kilt bears” and fought Indians, then went to Congress to fight for the rights of the hardworking settlers. He was among the most popular people in the country; his autobiography was so successful that he followed it with two more books. A play based on his exploits entitled

The Lion in the West

was a hit in New York in 1831, and marching bands would often greet him when he arrived in a city. He was so admired, in fact, that a faction of the Whig Party supported him for the presidency before the campaign of 1836.

But instead of going to the White House, on March 6, 1836, Crockett and about one hundred courageous Texans trapped in a century-old mission in San Antonio known as the Alamo were overwhelmed and killed by more than a thousand Mexican troops under the command of General Santa Anna. “Never in the world’s history had defense been more heroic,” reported an 1851 book entitled

The Great West.

“It has scarce been equaled, save at the Pass of Thermopylae.”

Crockett was the rare American who went from the quagmire of American politics to the real battlefields of freedom. People have long wondered—and speculated—how this national hero ended up dying at the Alamo. Others have taken the question even further and wondered if he did actually die there.

David Crockett, as he liked to be called, was a true child of the American frontier. His great-grandparents immigrated to America from Ireland in the early 1700s. His father, John Crockett, was born in 1753 in Virginia and was one of the Overmountain Men—patriots living west of the Appalachians—who fought in the Revolutionary War. Several members of the Crockett family were killed or captured and enslaved by Cherokees and Creek Indians in 1777. Davy Crockett was born in 1786, near the Nolichucky River in Tennessee. As did all children growing up on the frontier, Davy learned how to track, hunt, and shoot fast and straight, and was always comfortable in the backwoods. His father worked various jobs, from operating a gristmill to running a tavern, but struggled to support his family. When David Crockett was twelve years old, he was leased out as a bound boy to settle his father’s debt, tending cattle on a four-hundred-mile cattle drive. When he returned home, he was enrolled in Benjamin Kitchen’s school—and just four days later, after whupping the tar out of a bully, he took off from home to avoid his father’s wrath. His real knowledge came from practical lessons on how to survive on his own in the world.

After spending three years on the trail, finding work wherever it was offered as a hand, a drover, a teamster, and even a hatter, or simply hunting his food when it became necessary, he arrived back at the Crockett Tavern. It has been suggested that his adventures during these years, as he related them in his autobiography, served as a model for Mark Twain’s

Huckleberry Finn.

And Twain did acknowledge reading Crockett’s tales.

He took several jobs to settle the rest of his father’s debts; he worked for six months at a neighbor’s tavern, where, he wrote, “a heap of bad company meet to drink and gamble.” And when that note was satisfied, he began working for another neighbor, a farmer named John Canady. Crockett spent four years on the Canady farm, staying on for pay long after the debt was settled. During that period, the plain-speaking personality that was to prove so politically appealing years later first began to emerge. Upon meeting a lovely young girl, for example, he wrote that his heart “would flutter like a duck in a puddle, and if I tried to outdo it and speak, it would get right smack up in my throat, and choke me like a cold potato.”

It was on the Canady farm that he got his first real taste of book learning, using the money he earned to pay Canady’s son for reading lessons, and after several months’ hard studying, “I learned to read a little in my primer, to write my own name, and to cypher some in the first three rules in figures.”

David Crockett also began growing himself a reputation, not only as a straight talker but also as a straight shooter. The practice in shooting matches at the time was to split a beef carcass into four quarters, with contestants competing separately for each one. Entry was

twenty cents a shot. At one of those events, Crockett not only won the whole cow, he also won the “fifth quarter”—the hide, horns, and tallow.

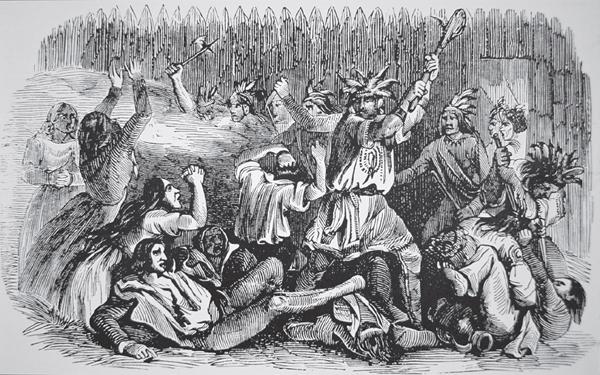

Before his twentieth birthday in 1806, he married and settled on a rented farm with the former Miss Polly Finley, a lovely girl he’d met at a harvest festival. He hunted bear and fowl, trapped forest animals, cleared acreage and planted crops, and fathered two boys, but there was a pull inside him that he couldn’t ignore. When war was declared against Great Britain in 1812, most of the Indian tribes sided with the British, believing their victory would end American expansion into the West. Tribes that had lived peacefully with settlers for decades suddenly went on the warpath. In August 1813, a thousand Red Sticks, as Alabama Creek Indian warriors were known, attacked Fort Mims and massacred as many as five hundred people. Crockett answered the call for help, signing up as a scout for Colonel Andrew Jackson’s militia army, which was marching south to avenge that attack.

Although Davy Crockett might well have seen it as his duty to fight for his country, he had other reasons for wanting to go. It’s possible he recognized an opportunity to make his name—and perhaps avenge the earlier murders of his kin. His farm was struggling, the money he would earn was desperately needed, and his unique skills would be very valuable during a war and just might secure his future. Polly begged him not to go, but he told her, “If every man would wait till his wife got willing for him to go to war, there would be no fighting done till we all got killed in our own house.”

After the largest massacre of settlers in the South at Fort Mims, Davy Crockett volunteered to fight for Colonel Andrew Jackson.

He quickly established himself as a reliable scout—although even he admitted his sense of direction was woefully lacking. Once, while hunting, he realized he was lost, and “set out the way I thought [home] was, but it turned out with me, as it always does a lost man, I took the contrary direction from the right one.”

No one knows how a man will react to battle until lead is flying, and Davy Crockett turned out to be a courageous soldier. In early November, General John Coffee, under the command of Andrew Jackson, led about a thousand dragoons in an attack on the Alabama Creek village of Tallushatchee. An estimated two hundred warriors were killed in the brief battle. At the Battle of Talladega a week later, Coffee’s men killed an additional 299 Creeks.

But Crockett also learned that war was a lot more complicated than he had anticipated. He found that he admired the courage of his enemies, and whenever it was possible, he avoided confrontations with them. At the same time, he grew to despise Andrew Jackson for the way he treated his men. “Old Hickory” was a brutal leader, who seemed not to care about his troops’ welfare. Although Crockett and other scouts did their best to hunt wild game for the militia, because of lack of food and supplies, countless men just got on their horses and rode home. Davy Crockett’s enmity toward Jackson that began during this campaign would follow the two men throughout their political careers—and spark Crockett’s ride to the Alamo.

Although Crockett earned his reputation as a frontiersman, it was his engaging personality that attracted people to him. He was a great storyteller, with a lively wit and an appealing aw-shucks personality. For many other men, lack of an education might have proved a barrier to a political career, but he learned how to use it to his advantage. Later on, he often reminded voters that he wasn’t one of those fancy men from back east who were always changing their minds to please their supporters, but just a regular man trying to do the best he could for his people. His political philosophy wasn’t particularly sophisticated: He stood up for what he believed, he didn’t seem to care if his positions were popular, and he wasn’t afraid to confront the most powerful men in the nation. He articulated his credo this way: “Be always sure you’re right, then go ahead.”

Colonel David Crockett, painted by A. L. DeRose, engraved by Asher B. Durand

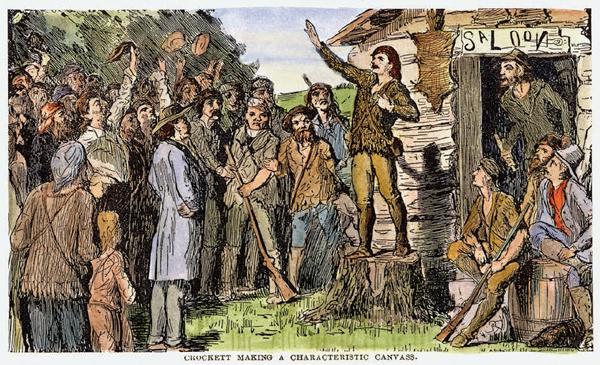

Davy Crockett’s political career began when his former commanding officer, Captain Matthews, was a candidate for the office of lieutenant colonel of the Fifty-Seventh Regiment of the Tennessee Militia and asked Crockett to run for major. Initially Crockett turned him down, explaining that he’d done his share of fighting, but the captain insisted. Finally, Crockett agreed. Only when it came time to make his campaign speech did he learn that his opponent would be Captain Matthews’s son. The meaning was clear to him: Matthews thought that running an unqualified hayseed against his son would guarantee victory. That insult got Crockett fired up, and he decided that if he was going to run, he should run against Matthews himself, for colonel. He stood on a tree stump and “told the people the cause of my opposing him, remarking that as I had the whole family to run against any way, I was determined to levy on the head of the mess.”

His audience, presumably delighted by the honesty of this speech, elected him to run the militia. Ironically, he became Colonel Crockett on the campaign trail rather than on the battlefield.

Crockett found that politics fit him well. But he didn’t forget where he came from. Consciously or not, he always advertised his frontier background, from the buckskin clothes he wore to the way he spoke to the political positions he supported. His greatest political strength was that ordinary people believed he understood their needs—the key requirement for a populist politician.

His wife Polly had died giving birth to their daughter, and he had remarried—to a woman with an eight-hundred-dollar dowry, so for the first time in his life he didn’t have to struggle to earn his keep. After moving to Lawrence County in 1817, he served as a town commissioner and helped draw the new county’s borders, then accepted an appointment as the local justice of

the peace. In 1821, his friends and supporters urged him to run for the Tennessee legislature, representing the counties of Lawrence and Hickman. As he remembered, “It now became necessary that I should tell the people something about the government, and an eternal sight of other things that I knowed nothing more about than I did about Latin, and law.”

On the campaign stump, Crockett would sometimes finish his speech by inviting everyone to join him for a drink, leaving his opponent to address a reduced crowd.

His opponent, he recalled, “didn’t think he was in any danger from an ignorant backwoods bear hunter.” Crockett stood up on the stump and told people that he had come for their votes, and that if they didn’t watch mighty close, he’d get them. In one campaign appearance, he told his listeners the story of a traveler who saw somebody beating on an empty barrel. When asked what he was doing, the man explained that just a few days earlier there had been cider in there and he was trying to get it out. Then Crockett added, “there had been a little bit of a speech in me a while ago, but I believed I can’t get it out.” The crowd laughed, and as he finished, he told them it was time to wet their whistles and led them to the liquor stand—leaving only a sparse few people to listen to his frustrated opponent.