Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (7 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Davy Crockett did not go to Texas to die at the Alamo but rather to live in a country he described in a letter to his children as “the garden spot of the world. The best land and the best prospects for health I ever saw, and I do believe it is a fortune to any man to come here.” There obviously were many reasons for him to leave Tennessee: He had been defeated by the Jacksonians and abandoned by the Whigs; he was separated from his wife; he was in debt and had no source of income; and for a man who had spent much of his life pursuing adventure, he lacked any current challenges. It also was the right place to reestablish his reputation:

Many people had begun wondering if all the attention and publicity had changed him. His exploits had been so obviously exaggerated that some doubted there was much truth to any of them. And it was not in his nature to back away from a fight.

The Alamo, Midnight

, lithograph by Frank Callcott

It’s impossible to know what his expectations were when he rode to Texas. Although it’s clear that he intended to become a land speculator and perhaps make “a fortune yet for my family, bad as my prospect has been,” some historians believe he planned to become involved in the politics of the new republic, maybe even run for president. He did write that he expected to be elected to the planned constitutional convention. When he learned the provisional government was offering 4,600 acres of good growing land to any man willing to fight for Texas’s freedom, he announced, “As the country no longer requires my services, I have made up my mind to go to Texas. I start anew upon my own hook, and may God grant that it be strong enough to support the weight that may be hung upon it.”

When he finally reached Nacogdoches in January 1836, he received a “harty [

sic

]

welcome to the country,” which included a cannon salute and invitations to social events held in his honor. In Nacogdoches, with sixty-five other men, he volunteered with the Texas Volunteer Auxiliary Corps, taking an oath to fight for six months in return for 4,600 acres. Before signing the oath, he insisted the word

republican

be inserted to ensure he would not be obliged to serve a dictatorship. In early February, provisional government president Sam Houston ordered him to lead a squad of expert riflemen to reinforce San Antonio de Bexar.

Until the preceding December, San Antonio had been occupied by more than a thousand Mexican soldiers. But after a five-day battle, the Mexican army had been defeated and had surrendered all property, guns, and ammunition to the Texans. The furious Santa Anna was determined to demonstrate to the settlers that resistance to Mexican rule was futile by retaking San Antonio—whatever the cost. He made it clear that there would be no quarter given, no prisoners taken; this would be a lesson the Texans would never forget. When 1,800 Mexican troops arrived in San Antonio on February 23, the 145 Texans—among them Davy Crockett—moved into the fortified mission called the Alamo.

Historians have been studying—and debating—the details of the battle for the Alamo for years without reaching agreement as to precisely how it unfolded. Apparently Sam Houston initially told his commander in San Antonio, Colonel William B. Travis, to destroy the mission and withdraw, believing his troops lacked the manpower and supplies necessary to defend it. Had Travis been able to comply with those instructions, most of the garrison could have survived, but he allowed his men to vote on whether to stay—and rather than retreat, they elected to stay and fight. When Santa Anna arrived and demanded their surrender, Travis responded with a cannon shot.

The Alamo was a small fortress, protected by limestone-block walls eight feet high and about three feet thick. Santa Anna’s army immediately began bombarding the mission, his artillery moving closer each day. On the twenty-fifth, an estimated three hundred Mexican troops crossed the San Antonio River and reached a line of abandoned shacks less than one hundred yards from the walls. It was an important strategic position from which to launch an assault; the Texans had to dislodge them. While the Alamo’s cannons and Crockett’s marksmen provided cover, a small group of volunteers reached the shacks and burned them down.

Travis pleaded for reinforcements, warning that his troops were running out of ammunition and supplies. On the twenty-sixth, 420 men with four artillery pieces set out from the fort at Goliad to relieve the garrison. When this force was unable to successfully ford the San Antonio River, they turned back, although about twenty men volunteered to try to reach the Alamo.

“The enemy … treated the bodies with brutal indignation.” They were thrown onto a pile and burned. The remains are believed to be in this casket in San Antonio’s San Fernando Cathedral.

Little is known about what was going on inside the Alamo during the siege, although one of the few survivors of the battle, a woman named Susanna Dickinson, wrote that Davy Crockett had entertained the garrison with his violin and storytelling. In records found after the massacre, Colonel Travis wrote of observing Crockett everywhere in the Alamo “animating men to do their duty.” It was also reported that Crockett had killed five Mexicans in succession as they tried to fire a cannon at the walls, and some claimed that he came within a whisker of killing Santa Anna, who had wandered into rifle range. There is some evidence that Crockett had managed to sneak out through Mexican lines to locate the small band of reinforcements waiting at Cibolo Creek and guide them into the Alamo. Several months after the battle, the

Arkansas Gazette

reported, “Col. Crockett, with about 50 resolute volunteers had cut their way into the garrison through the Mexican troops only a few days before the fall of San Antonio.” The meaning of that is clear, and it erases any doubts about his courage and

his integrity: Crockett had made his way out of what appeared to be a hopeless situation and could have escaped. Instead, he fought his way back inside to make a final stand with his men.

“Remember the Alamo” was the battle cry that led Sam Houston’s troops to victory at the Battle of San Jacinto six weeks later—and Americans have never forgotten the sacrifices made there.

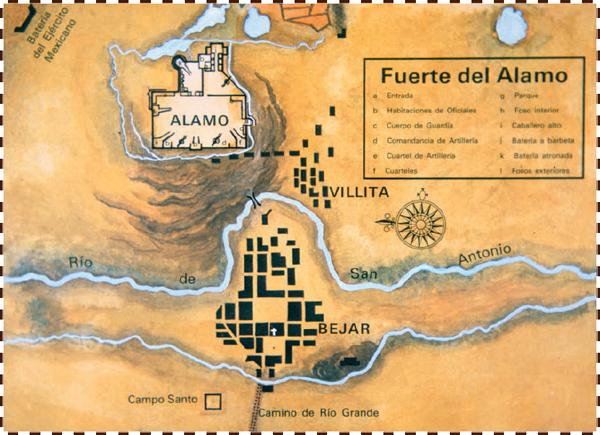

Above,

a map of the Alamo based on Santa Anna’s battlefield map;

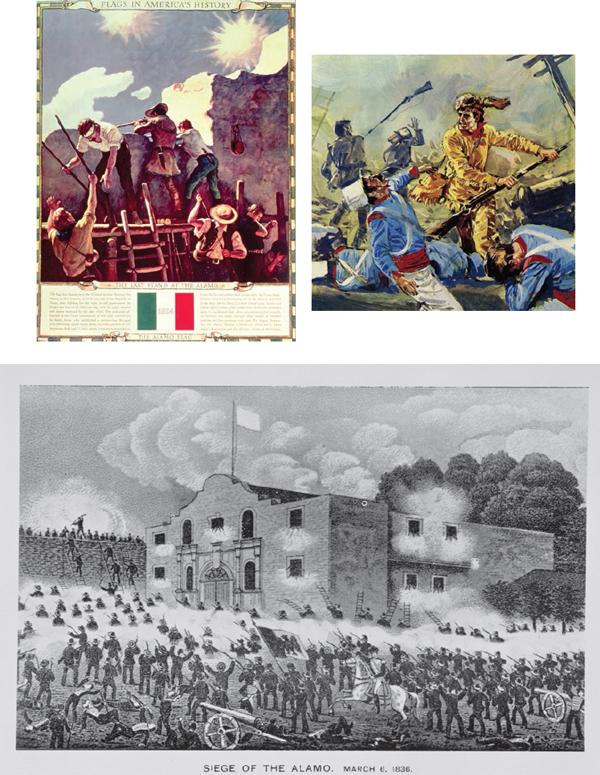

opposite, top left,

Newell Convers Wyeth’s

Last Stand at the Alamo; top right,

an imagined Crockett fighting his last battle;

bottom,

William H. Brooker’s engraving

Siege of the Alamo, March 6, 1836

Santa Anna’s army, which had been reinforced and numbered four thousand troops, attacked before dawn on March 6, advancing, according to Henry Howe in

The Great West

, “amid the discharge of musketry and cannon, and were twice repulsed in their attempt to scale the walls.” Susanna Dickinson later testified that when the attack began, Crockett had paused briefly to pray, then started fighting. After a fierce battle, Mexican troops breached the north outer walls. Although most of the defenders withdrew to the barracks and chapel, Crockett and his men stood in the open and fought. They fired their weapons until they were out of ammunition, then used their rifles as clubs and knives until they were overwhelmed.

It isn’t known how Davy Crockett died. There are several conflicting reports. A slave named Ben, who also survived the battle, claimed he had seen Crockett’s body surrounded by “no less than 16 Mexican corpses,” including one with Crockett’s knife still buried in it. Henry Howe reported, just fifteen years after the battle, that “David Crockett was found dead surrounded by a pile of the enemy, who had fallen beneath his powerful arm.” Most historians believe he was killed by a bayonet as he clubbed attackers with his rifle. He was forty-nine years old.

As happens often when heroes die without witnesses, alternative stories have persisted. One claims that Crockett and several other men either surrendered or were captured and brought before Santa Anna, who ordered their immediate execution. The purported eyewitness to that, a Mexican lieutenant named José Enrique de la Peña, supposedly wrote in a diary, found and published almost one hundred fifty years later, that Crockett had been executed, and “these unfortunates died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.”

There were only three survivors: Susanna Dickinson and her young child and the black slave, Ben. “The enemy,” wrote Howe, “exasperated to the highest degree by this desperate resistance, treated the bodies with brutal indignation.” Although there were some reports of mutilation, it is generally agreed that the bodies were thrown onto a pile and burned. The number of Mexicans who died in the attack is estimated at between six hundred and sixteen hundred men. Texans were shocked by the massacre. Almost immediately, “Remember the Alamo” became the rallying cry of the Texas army of independence. Less than two months later, on April 21, General Sam Houston’s army captured Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto, and the Republic of Texas was born.

The legend of Davy Crockett grew even larger after his death. A book entitled

Col. Crockett’s Exploits and Adventures in Texas … Written by Himself

was published the summer

after his death and, while clearly a work of fiction, served to reinforce his heroic sacrifice. Another story circulated claiming that Crockett was last seen standing at his post swinging his rifle as Mexican troops poured through a break in the walls. The memoir of Santa Anna’s personal secretary, Ramón Martínez Caro, published in 1837 in Mexico, reported, “Among the 183 killed there were five who were discovered by General Castrillón hiding after the assault. He took them immediately to the presence of His Excellency who had come up by this time. When he presented the prisoners, he was severely reprimanded for not having killed them on the spot, after which he turned his back upon Castrillón while the soldiers stepped out of their ranks and set upon the prisoners until they were all killed.” Although this was purportedly an eyewitness account, there is no direct evidence that Crockett was one of these men.