Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (3 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

On April 1, 1775, Boone and thirty axmen began construction of Fort Boonesborough, choosing a location in a defensible field “about 60 yards from the river, and a little over 200 yards from a salt lick.”

From all accounts, Daniel Boone was not a man of exuberant emotions. He kept his feelings contained and was respected for his cunning and his steadfast leadership. He was not a man who ever asked another to take a risk in his place. When a task needed to be done, he took the lead. The rescuers pursued the Indians for three days, finally sneaking up on them as they sat by a breakfast fire. Their first shot wounded a guard and alerted the others to escape. Two of the Indians were killed, and the three girls were freed without harm. This kidnapping and rescue later served as an inspiration for James Fenimore Cooper, who included a similar incident in

The Last of the Mohicans,

with the character Hawkeye modeled after Boone.

The Revolutionary War just brushed the frontier, and rather than facing the redcoats, the pioneers fought Native Americans supplied and supported by British forces headquartered in Detroit. It was questionable whether the Indians were actually fighting to protect the Empire or to maintain their own rights to live and hunt on the land. By 1777, Indians were focusing their attacks on Boonesborough, forcing the settlers to stay close to the fort. One afternoon, Boone was outside the perimeter when the Shawnees attacked. As Boone took up his long gun to return fire, a bullet smashed into his ankle and sent him to the ground. He was carried through the closing gate as Indian bullets ripped into the wooden walls.

The constant pressure of attacks kept the settlers confined, and by the end of the year, supplies were running low. In early February, Boone was asked to lead a twenty-seven-man expedition to the Blue Licks, a salt lick located several miles away. It was a very risky mission: Several weeks earlier, three Shawnee chiefs in captivity at Fort Randolph had been killed, and the tribe was seeking revenge. As Boone’s men were gathering vital salt, he was alone, hunting for provisions—and he was surprised and captured by a Shawnee war party. More than one hundred warriors were led by Chief Blackfish, a man Boone had met decades earlier while serving in Braddock’s campaign. Blackfish apparently respected Boone as the chief of his people and told him he intended to avenge the murders of the three Indian chiefs by killing everyone in the salt-gathering party, then destroying Boonesborough. Boone negotiated with him, finally offering to arrange the peaceful surrender of his men, who would then go north with the tribe. Chief Blackfish agreed.

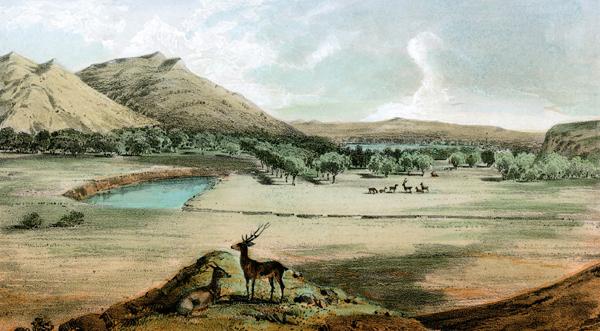

As this G. W. Fasel lithograph depicts, when Boone’s daughter and two friends were kidnapped by Indians in 1776, he tracked them down and rescued them—an episode that served as an inspiration for James Fenimore Cooper’s

Last of the Mohicans.

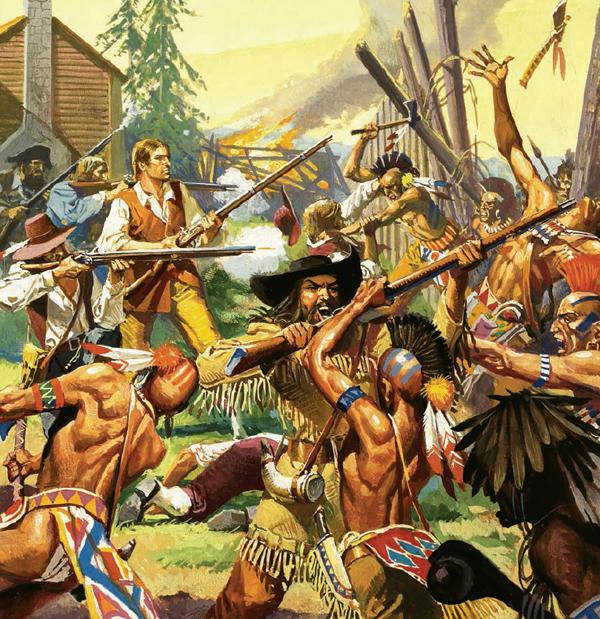

Boone was reputed to be the young nation’s greatest Indian fighter, as shown in this Baraldi painting of an attack on Boonesborough.

Boone led the Shawnees to his hunting party—and when his men saw him with the Indians, they suspected that he had betrayed them and prepared to fight for their lives. “Don’t fire!” Boone warned them. “If you do they will massacre all of us.” He put his reputation on the line, ordering his men to stack their arms and surrender. In the confusion, some men escaped and hurried back to warn the settlers.

Daniel Boone and the remaining members of the expedition went north with the Shawnees to the village of Chillicothe, where there was great debate on how to treat the prisoners: Some of the braves wanted to kill them, but apparently Boone convinced them otherwise. As the weeks went by, he actually was adopted into the tribe and given the Indian name Sheltowee, or “Big Turtle.” He was known to hunt and fish and play sports with the tribe, and there were even some stories that he took a bride. The Shawnees trusted him enough to take him to Detroit, where he met with the British governor Hamilton. But when he returned to Chillicothe, he found more than four hundred fifty armed and painted braves preparing to attack Boonesborough. He feared that the unprepared settlers would be slaughtered. Boone waited for the right opportunity, and in the confusion of a wild-turkey hunt, he managed to slip away.

He raced 160 miles in less than five days, on foot and horseback. He paused only one time for a meal. He reached Boonesborough still dressed in Indian garb, and his warning was met with great suspicion. The men who had escaped the original attack cautioned that he was cooperating with the Shawnees, pointing out that he had lived safely among the tribe for months and that he had returned while many of their relations remained captives. Finally Boone was able to convince the settlers to strengthen their wooden fortifications and, in an effort to prove his loyalty, suggested that instead of waiting for the attack, they take the offensive.

He and his friend John Logan led a thirty-man raiding party to the Shawnee village of Paint Creek on the Scioto River. After a trek of several days, they found it abandoned—meaning the main Indian force, then under the command of the Canadian captain Duquesne, was already on its way to the settlement. The raiding party made it back safely, and the cattle and horses were brought into the fort, which was made as secure as possible. Soon Boonesborough was surrounded by as many as five hundred Shawnee braves. British colors were displayed, and the settlers were told to either surrender, with a promise of good treatment, or fight and face the hatchet. Rather than fighting, Boone asked Captain Duquesne for a parley.

Boone and eight other men met with the Indians in a meadow beyond the settlement’s walls. Eventually they reached an agreement: The Ohio River would be the boundary between

the settlers and the tribes. As they shook hands, the Indians tried to grab Boonesborough’s leaders and drag them away, but carefully hidden sharpshooters opened fire. Boone and his men retreated, and an eleven-day siege began. The enemy made several efforts to break into the fort, but riflemen inside the garrison released a steady stream of accurate fire on anyone who came within range. When the Indian force broke off the attack, thirty-seven braves had been killed and many more wounded, while inside the walls only two settlers had died and two were wounded. The resistance, led by Daniel Boone, had saved the settlement.

But within weeks, Boone was accused of treason. Two militia officers—whose kin had been taken on the salt-lick expedition and were still being held captive in Detroit—claimed he had been collaborating with the Indians and the British. He was accused of surrendering the original expedition at the salt flats, consorting with the British in Detroit in their plan to capture the settlement, intentionally weakening Boonesborough’s defense by taking thirty men on the “foolish raid” on Paint Creek, and leaving the fort vulnerable by bringing its leadership outside to negotiate with Blackfish. The penalty for treason was death by hanging.

Boone’s trial was held at another settlement, Logan’s Station. With few records available, it is difficult to reconstruct events. His accusers were Richard Callaway and Benjamin Logan. Callaway testified, “Boone was in favor of the British government and all his conduct proved it.”

Boone insisted on representing himself rather than retaining a lawyer. He testified that both his salt expedition and the settlement were outmanned and outgunned, and neither of them was strong enough to survive a surprise attack. To prevent a massacre, he had been forced to “use some stratagem,” telling the Indians “tales to fool them.” After hearing his testimony, and perhaps taking into account his good name, the judges found him not guilty—then promoted him to the rank of major.

Boone accepted the acquittal but could not forgive the insult, so he left Boonesborough and founded a new settlement in an area known as Upper Louisiana, which actually was in present-day Missouri. When asked why he’d left Kentucke, he replied, “I want more elbow room.” In recognition of his accomplishments, the Spanish governor of that region granted him 850 acres and appointed him commandant. He settled there with his family but couldn’t stay settled long.

Perhaps still angry about the false accusations, in 1780 he finally joined the Revolution, acting as a guide for George Rogers Clark’s militia as they attacked and defeated a joint British and Indian force in Ohio. In that attack, his brother Ned was shot and killed. Apparently believing they had killed the great Daniel Boone, the Shawnees beheaded Ned Boone and took his head home as a trophy.

This Currier and Ives hand-colored lithograph by Fannie Flora Palmer,

The Rocky Mountains—Emigrants Crossing the Plains

, 1866, illustrates the barren beauty of the frontier—although Palmer never left New York.

A year later, Daniel Boone stood for election to the Virginia Assembly. He would be elected to that body three times.

Two years later, at the Battle of Blue Licks, the then lieutenant colonel Daniel Boone warned his commanding officer that the militia was being led into an Indian trap. He explained that the Indians had left a broad and obvious trail, which was contrary to their

custom and “manifested a willingness to be pursued.” Boone believed that “an ambuscade was formed at the distance of a mile in advance” and urged him not to cross the Licking River until the area could be properly scouted or reinforcements known to be marching toward them arrived. But as the commanders debated their strategy, a headstrong young Major McGary ignored Boone’s advice and instead mounted and charged the enemy. When he was in the middle of the stream, he paused, waved his hat over his head, and shouted, “Let all who are not cowards follow me!” As the rest of the men cheered and followed, Boone supposedly said, “We are all slaughtered men,” but still joined the attack. As pioneer historian Howe described it, “The action became warm and bloody … the slaughter was great in the river.” When the trap was sprung, as Boone had warned, he fought courageously and helped organize the militia’s retreat. Boone himself was in desperate trouble: Several hundred Indians were between him and the main force. Howe wrote, “Being intimately acquainted with the ground, he, together with a few friends, dashed into the ravine which the Indians had occupied, but

which most of them had now left to join the pursuit. After sustaining one or two heavy fires, and baffling one or two small parties, who pursued him for a short distance, he crossed the river below the ford, by swimming, and entering the wood at a point where there was no pursuit, returned by a circuitous route….”