Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (10 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

When General S. W. Kearny’s troops were surrounded and greatly outnumbered by Mexican forces, Carson and Navy Lieutenant Beale crawled through enemy lines, then ran almost thirty miles barefoot to save the besieged soldiers.

When the war ended, Commodore Stockton, who had been involved in the American revolt, declared Frémont governor of California. Six weeks later, General Kearny, claiming to be acting on government orders, charged Frémont with insubordination, a serious military offense, and named himself acting governor. Frémont immediately dispatched Carson to Washington to plead his case before President Polk. While in the capital, Carson stayed in Frémont’s home, choosing to sleep outside on the porch rather than in a stuffy bedroom. Frontiersman Kit Carson was a sensation in Washington, though there was little about his physical appearance that reflected his exploits. The blood-and-thunder books had depicted him as a giant, America’s first action hero, so people were greatly surprised that in the flesh this living legend actually was a small, stoop-shouldered, bowlegged, and freckled man, and that he responded to questions with simple, often one-word answers and spoke in a voice “as soft and gentle as a woman’s.” His appearance was so different from expectations that one man who had traveled a long distance to meet the great Indian fighter looked him up and down and said, “You ain’t the kind of Kit Carson I am looking for.” In fact, Carson’s fame was so great across the country that there was a lively business in Kit Carson imposters.

The real Kit Carson was not impressed by his own celebrity. In fact, after making four more trips across the country as President Polk’s personal courier, Carson happily mounted up and headed home.

At this point in his life, Carson and one of the men he’d traveled with, Lucien Maxwell, decided to build a real homestead in the Rayado valley, about fifty miles east of Taos. “We had been leading a roving life long enough and now, if ever, was the time to make a home for ourselves,” he explained. “We were getting old and could not expect much longer to continue to be able to gain a livelihood as we had been doing for many years…. We commenced building and were soon on our way to prosperity.”

It was impossible for him to stop adventuring, though, and he continued to accept commissions from the government. He led other survey teams into the Rockies; he drove

a herd of 6,500 sheep from New Mexico to the markets of California, where they sold for $5.50 per head; and at times he pursued Indians and outlaws. Not long after he had settled down with his third wife, “Little Jo,” he learned that a Jicarilla (Apache) Indian raiding party had attacked a small group riding toward Santa Fe, killing merchant James White and another man and taking his wife, daughter, and a black female slave captive. The Jicarillas had then killed the child with one blow of a tomahawk and thrown her body into the Red River. Carson couldn’t let this stand. He saddled up and joined the posse headed by an army major. They tracked the Indians for twelve days over harsh terrain. In camps along the way they found scraps of Mrs. White’s dress and some of her possessions. When they finally found the Indian band with their captives, Carson wanted to attack immediately, but the major insisted that they instead parley with them and try to arrange a trade for the women. Carson was furious, knowing that the Indians had no interest in talk, but he was a man who followed orders. As the major waited, a single rifle shot rang out from the Indian camp, striking that officer squarely in the chest. In an incredible coincidence, only minutes earlier he had taken off his buckskin gauntlets and put them in his breast pocket. The buckskin had saved his life.

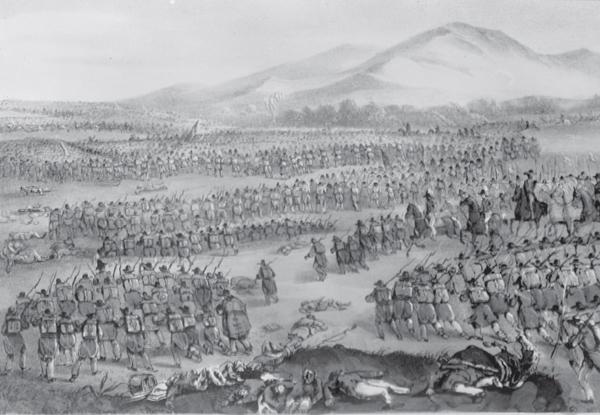

The 1847 Battle of Buena Vista was one of the bloodiest fights of the Mexican-American War. More than 3,400 Mexican troops and 650 Americans under the command of General Zachary Taylor were killed or wounded before Santa Anna withdrew in the night.

The outnumbered Indians scattered, leaving behind their belongings, but the major’s order to charge came too late. They found Mrs. White’s body and determined “her soul had but just flown to heaven.” She had been shot through her heart with an arrow only minutes earlier. Then Carson found something he would never forget. According to his biographer,

Among the trinkets and baggage found in the [Indians’] camp there was a novel, which described Kit Carson as a great hero, who was able to slay Indians by scores. This book was shown to Kit and, he later wrote, “It was the first of the kind I had ever seen … in which I was made a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundreds…. I have often thought that perhaps Mrs. White, to whom it belonged, read the same and knowing that I lived not very far off, had prayed to have me make an appearance and assist in freeing her. I consoled myself with the knowledge that I had performed my duty.”

The ride home had been difficult. The posse was caught in a blizzard and one of their men froze to death. Later Carson learned that the Jicarilla had been caught in the same storm. And he shed no tears when he learned that without the furs and blankets that they had been forced to leave behind in the camp, many of them had frozen to death as well.

Sometime in 1849, Carson was told about a plot to murder two merchants. A man appropriately named Fox had hired on to guide the merchants on a trip to buy goods they

would use for trade. To accomplish that, they were carrying a large sum of money. In fact, Fox intended to kill them on the trail and then leave the bodies in the wilderness. Fox made the mistake of trying to enlist a shady character living in Rayado to help him. This man turned down the offer and, when Fox went back out on the trail, told the story to the local army post commander. When Carson learned of it, he gathered a small posse and raced almost three hundred miles through Indian territory to catch up with the party, arriving just in time to save the two merchants. Although they offered Carson a substantial reward, he refused to accept even one penny and instead took Fox back with him to jail.

Kit Carson fought Indians, then went to Washington to fight for those same peoples, but his actions eventually caused him to be reviled by the tribes of the Southwest.

As the American frontier moved steadily westward, Indian resistance to the settlers increased. The pioneers lived in fear of sudden and deadly attacks. Few people dared leave a settlement without first making careful preparations. It would be impossible to determine how many encounters Kit Carson had with the tribes, but it is accurate to state that precious few men could match that number. He had come to be known as the greatest Indian fighter in the West. No man was more qualified or better prepared to deal with the tribes, whether the encounter required words spoken over a shared peace pipe or the skilled use of a rifle, knife, or hatchet.

But Carson avoided violence when possible. For instance, in the summer of 1851 he went east to St. Louis to visit his daughter and buy provisions for the winter, and on his way back, a few miles after crossing the Arkansas River, he encountered a band of Cheyennes. Carson could not have known these Cheyennes were on the warpath; a chief had been flogged by an American officer and they were out for revenge. Carson knew his party was too small and ill equipped to outrun them; he ordered the wagons to stay close and told his men to have their rifles ready. The Indians’ war party shadowed them for more than twenty miles. When the caravan made camp for the night, Carson invited the advance party to join him for a talk and a smoke.

In 1865, Kit Carson, the nation’s most famous Indian fighter, told a congressional committee, “I came to this country in 1826 and since then have become pretty well acquainted with the Indian tribes, both in peace and at war. I think, as a general thing, the difficulties arise from aggressions on the part of the whites.”

These young braves did not recognize Carson. Although they would have recognized his name, they would not have known what he looked like. So they certainly did not suspect that this white man spoke their language. As the pipe was passed, the Indians began speaking to each other in the Sioux language, so that if any of the white men escaped this trap, the Sioux would be blamed for the attack. It was not an unusual ruse. But as they continued smoking into the night, they eventually resorted to their own tongue. Finally they revealed their plan: When the pipe was next passed to Carson, he would have to lay down his weapon to take it, and at that moment they would attack and kill him. Then they would kill the other members of the party.

Carson understood every word, and he waited. When it was his turn, rather than taking the pipe, he grabbed his rifle and stood in the center of the circle, ordering his men to ready their weapons. The Cheyennes were stunned. Speaking to them in their own language, Carson demanded to know why they wanted his scalp. He had never been guilty of a single wrong to the Cheyennes, he said, and in fact their elders would tell them that he was a friend. Finally he ordered them out of his camp, warning that anyone who refused to leave would be shot and that if they returned, they would “be received with a volley of bullets.”

Carson knew his threat would not stop the Indians indefinitely, but it would buy time. At the darkest point of that night, he took a young Mexican runner aside and instructed him to run as fast as possible to Rayado and return with soldiers. Their lives depended on him, he whispered. The boy was long gone by sunrise. It was said that young runners could cover more than fifty miles in a day. Almost a full day passed before the Cheyennes reappeared. They were wearing their war paint. As their braves approached, Carson warned them that a scout had been sent ahead for help. If they attacked, he admitted to them, the Cheyennes would suffer large casualties but eventually they would win. He knew that. But he had many friends among the soldiers and they would know which people had committed this crime “and would be sure to visit upon the perpetrators a terrible retribution.”

Indian scouts found the boy’s footprints, but with his long lead time they knew he could

not be caught. Reluctantly, the war party withdrew. Two days later an army patrol under the command of Major James Henry Carleton arrived to escort Carson’s party safely to Rayado.

As ruthlessly as Kit Carson often fought against the Indians, he also fought for them. In the early 1850s, he became the Indian agent—the government’s representative to the tribe—for the Mohauche Utes, or Utahs, and several Apache tribes. While the Apaches continued to fight, initially the Utes remained at peace with the white man. Carson worked for the best interests of the tribe and at times fought doggedly with officials in Washington. He even requested permission to live with the Utes on their reservation, which was denied. Utes came almost daily to his ranch for food and tobacco, which he had paid for himself and happily supplied to them. He was so respected by the tribe that he became known as “Father Kit,” and General Sherman once remarked, “Why his integrity is simply perfect. They [the Utes] know it, and they would believe him and trust him any day before me.”