Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (9 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

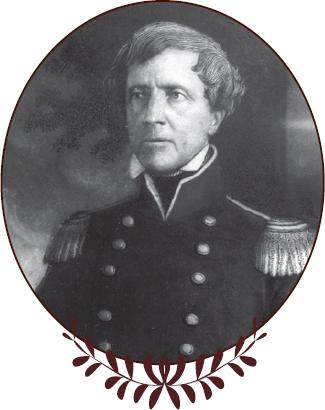

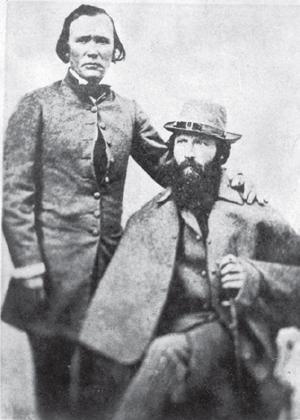

Kit Carson (

left

) and John Frémont came from completely different backgrounds, but their adventures introduced America to the possibilities of the great West.

The two men hardly could have been more different. While the rough-hewn Carson had never learned to read or write, Frémont was a polished, ambitious mathematics teacher who was married to the daughter of powerful United States senator Thomas Hart Benton. Senator Benton, the political champion of Manifest Destiny, apparently had helped his son-in-law get his army commission, then convinced Congress to support his explorations.

The twenty-eight-man party that would eventually make both Frémont and Carson national heroes departed St. Louis on June 10, 1842. Several of Carson’s closest friends had joined the expedition, mountain men he respected and trusted, men he wanted to have by his side in a fight. When they reached Fort Laramie, Wyoming, they learned that almost a thousand Sioux had attacked a party of trappers and Snake Indians and were still in the region. The expedition was advised to turn back or risk being massacred. Frémont refused, replying that his government had directed him to perform a certain duty and he intended to do so. If he perished in the effort, he was confident his government would avenge his death. Carson admired the Southerner’s fortitude and courage, and that helped cement their friendship.

Carson and Frémont would save each other’s lives as they fought Indians, outlaws, Mexicans, and the elements to survey the western wilderness.

The expedition accomplished each of its objectives, and Frémont’s beautifully written reports, which were reprinted in newspapers throughout the country, thrilled Americans with

their vivid descriptions of a magnificent landscape and vast regions waiting for settlement. Frémont was celebrated as “the Pathfinder,” and Kit Carson was credited as his trusted scout. While Frémont returned to Washington to lay plans for a second expedition, Kit Carson married for the third time—his second wife having left him to join the migration of her tribe—this time to a Mexican, Senora Josefa Jaramilla, with whom he would have three children. To appease her family he agreed to convert to Catholicism.

Frémont and Carson’s second expedition, intended to map the remainder of the Oregon Trail, began in the summer of 1843 and eventually brought them in sight of the magnificent Cascade Range. During their return journey, they became snowbound in the Sierra Nevada and faced starvation. Food was so scarce that their half-starved mules “ate one another’s tails and the leather of the pack saddles,” and Frémont gave his men permission to eat their dogs. Somehow Carson managed to scrounge enough food for them to survive. During the trek through the deep snow, Frémont and Carson left their party to scout for a path over a raging, icy river. As Frémont wrote, “Carson sprang over, clear across a place where the stream was

compressed …” but when Frémont tried to follow, his moccasins slipped on an icy rock and he fell into the river. “It was some few seconds before I could recover myself in the current, and Carson, thinking me hurt, jumped in after me, and we both had an icy bath.”

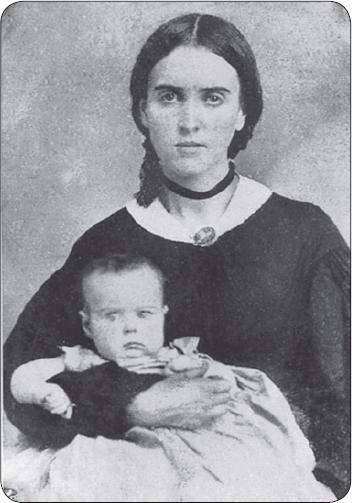

Josefa Jaramilla-Carson with Kit Carson Jr.

After spending the winter at Sutter’s Fort in California, the expedition set out for home. To get there, they had to go through the Mojave Desert. In addition to heat and thirst, they had to endure several Indian attacks. After Indians stampeded their livestock, Carson took off after them. As Frémont later described it, “Carson may be considered among the boldest…. Two men, in a savage desert, pursue day and night an unknown body of Indians into the defiles of an unknown mountain—attack them on sight, without counting numbers, and defeat them in an instant.”

As they made their way out of the Mojave, they encountered a Mexican man and boy, survivors of an Indian attack. They had been ambushed by an estimated thirty Indians, they said; two men had been killed in the attack, their two female cooks had been captured, and twenty horses had been stolen. Carson and his friend Richard Godey volunteered to go after the captured women. The two men tracked the Indians for two nights and found them at dawn. They silently crawled into the camp, hiding among the stolen horses. When the horses stirred, alerting the Indians, Carson and Godey had no choice but to attack. They raced into the camp. Carson raised his rifle and shot the leader dead. Godey’s first shot missed, but his second shot killed his target. The Indians hesitated to respond, believing the two men must be the point of a much larger group waiting in ambush.

Carson and Godey recovered fifteen horses and then began searching for the captured women. Instead, they found the bodies of the two Mexican men who had been killed, staked to the ground and mutilated. In response they “took the hair” of the Indians they had shot, honoring the counting-coup tradition.

Frémont’s reports transformed Kit Carson into a frontier legend, the brave tracker who saved the expedition in the snowbound mountains, then practically single-handedly attacked and defeated thirty wild Indians. While the true story was amazing enough, reporters and dime novelists exaggerated it even further, attributing to Kit Carson all the ideal traits—humility, loyalty, and bravery—characteristic of this new country. The first of these “blood and thunders,” as these books were known,

Kit Carson: Prince of the Gold Hunters,

told the fictional story of Carson rescuing a kidnapped young girl from the Indians. Carson, who didn’t know how to read, had to have these stories read to him.

Frémont’s third expedition left St. Louis in the summer of 1845, initially intending to map the source of the Arkansas River. But when the expedition accomplished this objective, he

continued on to California, which was still Mexican territory, to support the growing number of American settlers there who wanted to join the United States. The superior number of Mexican troops forced Frémont to go north, making camp at Klamath Lake, Oregon. One night in May 1846, as the party slept, Indians crept into camp and killed Carson’s friend Basil Lajeunesse with a single hatchet blow to his head. In the ensuing battle, two more of Frémont’s men were killed. Several attackers also died and, as Frémont later reported, the enraged Carson continued to pummel the body of one of them, beating his face into pulp.

That wasn’t enough to satisfy him, though; to avenge Lajeunesse’s death, he led an attack on a Klamath tribe fishing village where 150 braves lived. When Carson’s rifle misfired during the battle, a Klamath warrior took aim at him with a poisoned arrow. Frémont acted instantly to save his life—“he plunged the rowels of his spurs deep into his horse” and trampled the enemy warrior. By the end of the day, in what became known as the Klamath Lake Massacre, most of the Indians had been killed and their village had been burned to the ground. Only later was it discovered that this tribe probably was not involved in the initial attack.

For more than a century,

The Youth’s Companion

was one of the country’s most popular magazines for children. This heroic illustration was published in about 1922.

Coincidentally, on the day of the massacre, President Polk called on Congress to declare war on Mexico. Frémont’s mapping party was almost instantly transformed into a fighting force called the California Battalion. Carson was given the rank of lieutenant. Returning to California, Frémont led a successful insurrection and declared himself military governor of the new American territory. Carson was dispatched to Washington, D.C., to inform President Polk of the victory, a cross-country journey he promised to make in sixty days. His planned route would take him through Taos, where he hoped to spend at least a brief time with his wife, whom he hadn’t seen in more than a year. But when he was only days from home, he encountered General Stephen Kearny and his Army of the West, which had successfully seized New Mexico for the United States, and was en route to California. Kearny ordered Carson to turn around and guide him to San Diego and to send Frémont’s dispatches to President Polk with another rider. Although he was only one long ride from his wife, he responded, “As the General thinks best,” and joined his troops.

By the time Kearny’s one hundred dragoons got to California, the situation there had changed drastically. The Mexicans had counterattacked, and Frémont was besieged by Californios, Mexican troops carrying eight-foot-long lances. Kearny clearly underestimated the Mexican troops when he launched an attack on the village of San Pasqual. By the end of the second day of fighting, almost fifty of Kearny’s vastly outnumbered Americans had been killed or wounded, and the survivors were trapped on a hilltop without sufficient food, water, or ammunition. If they were not quickly reinforced, they would face annihilation. During the night, Kit Carson and Navy Lieutenant Beale removed their shoes and silently slipped through enemy lines, coming so close to being caught that Carson later claimed that “he could distinctly hear Lt. Beale’s heart pulsate.” Knowing they could not risk using the trails, the two men ran, walked, and crawled almost thirty miles barefoot through the sagebrush and cactus of the rocky terrain, the prickly pears digging into their bare feet. They raced through two nights without food or water until they finally reached American lines in San Diego. Carson had chosen the more difficult terrain to cover so arrived after Lieutenant Beale. Kearny’s troops were preparing to make a final, desperate attempt to break out when the two hundred American reinforcements sent by Carson and Beale reached them. The Mexican army withdrew and the remnant of Kearny’s battalion was saved. It took Lieutenant Beale more than a year to recover fully from this experience.