Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (32 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

The James brothers managed to get away, eventually rejoining Quantrill in an ill-fated attempt to ride to Washington and kill President Lincoln. Several weeks after General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, a militia force surprised Quantrill’s men near Taylorsville, Kentucky; Quantrill was shot and died a month later of his wounds. There are conflicting reports about exactly what happened next. According to T. J. Stiles, author of the acclaimed biography

Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War,

James was captured by Union forces and held prisoner in a hotel that had been used as a hospital, where he was forced to surrender. But according to Judge Thomas Shouse, who had been friends with both James brothers, Jesse told him that he had been shot in his right lung by a “mini-ball” fired by drunken Union soldiers as he rode into Lexington, Missouri, carrying a white flag of surrender, prepared to sign the Union’s loyalty oath. He claimed that was the seventh time he had been wounded. His horse was killed, and as he later wrote, “I ran through the woods pursued by two men on horseback…. I was near a creek. I lay in the water all night, it seemed that my body was on fire.” A farmer plowing nearby helped him, and eventually he made it back to his family, who by then were living in Rulo, Nebraska. For eight weeks he hovered between life and death, at one point telling his mother, “I don’t want to die in a northern state.” Among the women who nursed him back to health was his lovely cousin Zerelda “Zee” Mimms, whom he would later marry.

He later claimed that while he was recovering, five militiamen came to his house, prepared

to kill him. It was fight or die, he later wrote: “Surrender had played out for me.” He struggled to get out of bed, fired once through the front door, then flung it open, and with a pistol in each hand, commenced firing, bringing down four of them. He knew then that he would never be allowed to live peacefully.

At the end of the war, Frank James surrendered in Kentucky, then violated postwar regulations by sneaking home. On his dangerous journey, he got into a gunfight with four Union soldiers; he killed two of them and wounded a third, and a bullet nipped him in the left hip. He made it home, but he couldn’t stay there. For men like the James brothers, returning to any kind of normal civilian life proved impossible. The war had transformed them into different people; after what they had seen, after what they had done, after all the destruction the war caused, there was nothing for them to go back to. And, in addition, as Jesse had learned, Union militiamen weren’t about to forgive them, no matter what Lincoln and Grant had promised.

In addition to Frank and Jesse James, among the people permanently scarred by the war were Cole and James Younger. They were farm boys from Kansas, two of the fourteen children of Henry Washington Younger. Although a slave owner, Henry was a Union sympathizer, as was his whole family. But when Jayhawkers began raiding the family farm, stealing livestock

and destroying property, Cole Younger turned against them and eventually joined Quantrill’s Raiders. Any ambivalence he might have felt disappeared when Union militiamen killed his father. Cole rode into Lawrence, Kansas, with Quantrill and Frank James, and when they rode out a day later, all of them would be bonded forever.

The outlaw Cole Younger in 1903; after serving twenty-five years in prison, he published his autobiography and partnered with Frank James to create a Wild West show.

Cole’s little brother James also joined Quantrill and stayed with the Raiders when Cole joined the regular Confederate army and, as a captain, led troops into Louisiana and California. When the Younger brothers finally made it home after the war, the family farm was a ruin.

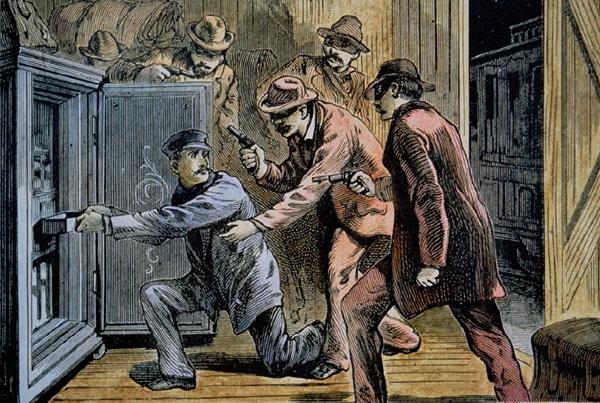

Several of the former guerrillas stayed loosely together during Reconstruction under the leadership of Little Arch Clement, who is generally believed to have turned them into outlaws. On the cold morning of February 13, 1866, they began to show the world the valuable lessons they had learned, when about thirteen of them rode into Liberty, Missouri, dressed in the long blue coats of the Union soldiers. There were only a few people on the street, and no one suspected that this was the beginning of a bank robbery—because never before in peacetime had a bank robbery taken place in the light of day.

There is no record of exactly whose idea it was to hold up the Clay County Savings Bank in broad daylight, but several important facts linked the plan directly to the James brothers: The bank was owned by a man named Greenup Bird, who years earlier had been especially harsh on Reuben Samuel in negotiations over a debt. Also, disguising themselves as Union soldiers was an old Raiders trick. And, finally, the bank was filled with Yankee dollars.

Using the same raiding tactics they had perfected during the war, the men dismounted and took their assigned positions, creating a series of perimeters around the bank. Jesse wasn’t among them, because he was still recovering from his chest wound and unable to ride, although it is believed that he helped plan the job. Frank James and Cole Younger entered the bank and pulled their pistols. The only other person in the bank was Bird’s son. He and his father put all the bank’s money into a large grain sack. The robbers escaped with $58,072.64, the modern-day equivalent of almost a million dollars.

No one had been hurt during the robbery, but the gang made its escape a-whoopin’ and a-hollerin’ out of town—and wildly firing guns in the air. As the men raced down the main street, two other young men watched them—and for no reason anyone could ever figure, Arch Clement took aim and shot one of them dead. As was later remarked, Arch just liked killing. A few days after the robbery, the victim’s family reportedly received a letter signed by a man no one had ever heard of at the time named Jesse James, who apologized for the murder and stated that the gang had not intended to kill anyone.

The take was so large that if money had been the motivation, most members of that crew

could have quit robbing right then and lived comfortably for the rest of their lives. Some of them did, in fact, but not the James boys, nor the Youngers. For them, this was just the beginning of a crime spree that would last almost two decades and grow to include dozens of bank, train, and stagecoach robberies.

The first robbery in which Jesse was believed to be an active participant took place at the end of October, when bandits stole $2,011.50 from the Alexander Mitchell and Company bank in Lexington, Missouri. The robbers followed a pattern that was to become familiar: One man would ask a clerk to change a large bill, and then at least one other “customer” would pull his gun and announce the holdup. Six weeks after this job, the state militia caught up with Arch Clement, drinking in a Lexington saloon. Clement got on his horse and tried to ride his way out of it, but he was shot in the chest. A second shot knocked him off his horse. As he lay dying in the dirt, trying to cock his revolver with his teeth, he said, “I’ve done what I’ve always said I would do … die before I’d surrender.”

In the months following Clement’s death, several members of his gang either were caught and hanged or just had enough and rode off, leaving the core crew that gained renown as the James-Younger Gang. Due primarily to the eventual notoriety of Jesse James, it became the best-known gang in the Old West, though there are historians who doubt it deserves that recognition.

As bank robbing became a more popular crime, it became more and more difficult to pin any holdup on a specific gang, and even when the gang could be identified, it was almost impossible to know who exactly was riding with it at that point. The better known the James-Younger Gang became, for example, the more robberies were attributed to it, as if there were some status attached to being held up by Jesse James and Cole Younger. The next job attributed to them—that they may or may not have pulled off—was the Hughes and Wasson Bank in Richmond, Missouri; fourteen robbers stole about thirty-five hundred dollars—and killed three men who got in their way. Four former bushwhackers were eventually caught and lynched for this robbery.

But there is no doubt that Jesse James and Cole Younger led eight men into Russellville, Kentucky, on May 20, 1868, and rode out with exactly $9,035.92. As the gang made its escape, shooting into the air to discourage gawkers, one member shot at the metal fish weather vane atop the courthouse, sending it spinning. Almost a century later, that historic weather vane, with a bullet hole through it, could still be seen on the roof of the new courthouse, where it had been placed to honor the town’s history. One man was eventually convicted for that robbery, for which he served three years in prison.

As the robberies continued, the fame—and fear—spread. On June 3, 1871, a gang of men rode into Corydon, Iowa, intending to rob the county treasurer of tax receipts. As usual, they began by asking to change a large bill. But before they pulled their guns, they were informed that the safe was time locked. The kindly clerk suggested they could get change at the Ocobock Brothers Bank, which was opening that very day. They thanked the man and helped celebrate the new bank’s opening by stealing about six thousand dollars. Following this robbery, authorities hired the famed Pinkerton detective agency, renowned as the best modern crime solvers in the world, to finally bring this gang to justice.

The banks began falling like targets in a shooting gallery, and the gang began expanding its efforts. In 1872, the men stole the cash box from the Kansas City Exposition. Although most reports claim they got almost ten thousand dollars, the treasurer later claimed it was only $998. Shots were fired while they were making their getaway, and a young girl was slightly wounded. Soon afterward, an anonymous letter published in the

Kansas City Weekly Times

admitted, “It is true I shot a little girl, though it was not intentional; and if the parents will give me their address through the columns of [this newspaper] I will send them money to pay her doctor’s bill.”

In July 1873, the gang pulled off its first train robbery outside Adair, Iowa. The men removed a track rail, believing that this would force the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific conductor to stop the train. Unfortunately, the train derailed, killing the engineer and injuring many passengers. The gang boarded the train dressed in the white sheets of Ku Klux Klan members and stole $2,337. During the holdup, Jesse supposedly told the passengers that the gang was stealing from the rich to help the poor. The railroad immediately offered a $5,500 reward for the conviction of these robbers. Six months later, the gang robbed its first stagecoach, this time wearing Union army blue coats and getting away with anywhere between one thousand and eight thousand dollars—but returning a purse untouched to a man who claimed to have fought for the Confederacy.

At the end of January 1874, the gang stopped an Iron Mountain Railway express near Gads Hill, Missouri. For the first time, the men robbed train passengers—asking each person to hold out his hands for inspection, permitting workingmen with calluses to keep their money. They took $10,000 from the safe and $3,400 from passengers. As they were making their escape, one of the robbers, later identified by his handwriting as Jesse James, left a note reading, “The most daring robbery on record! The southbound train on the Iron Mountain Railroad was stopped here this evening by five heavily armed men and robbed of _____ dollars…. The robbers were all large men, none of them under six feet tall. They were masked …”

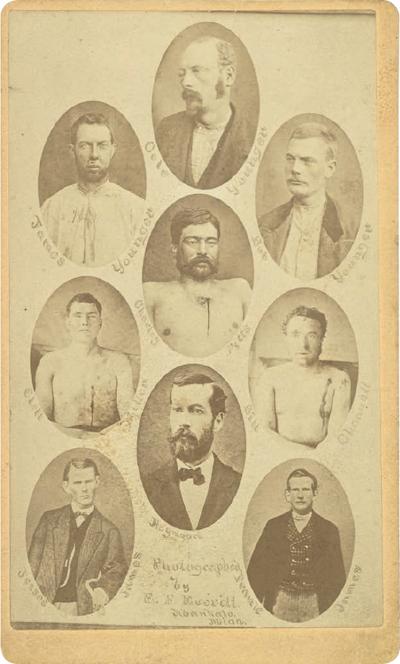

The fame of the James-Younger Gang resulted in individual

cartes-de-visite

, collectible business-card-size portraits, of the best-known members. This 1876 composite includes the eight most infamous outlaws and their final victim.