Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (29 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

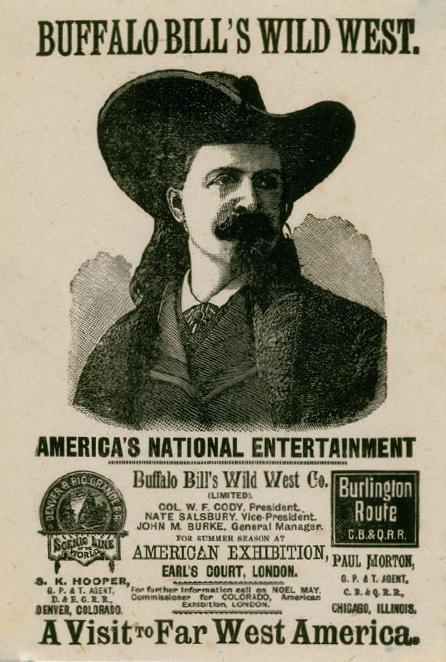

The show gave two command performances for Queen Victoria, one of them causing a sensation. As Cody wrote, “When the standard bearer passed the royal box with Old Glory her Majesty arose, bowed deeply and impressively to the banner, and the entire court party came up standing … and all, saluted.” This marked the first time in history that a British monarch had saluted the American flag.

As soon as the show returned from its triumphant tour, Annie Oakley resigned. Various reasons were given but they all centered on the same issue: She just didn’t like Lillian Smith. She resumed touring as a solo act, briefly joined a competing Wild West show, and even appeared onstage in a trifle called

Deadwood Dick.

Smith eventually fell in love with a cowboy and left the show as well, darkening her skin and touring in

Mexican Joe’s Wild West

show as Princess Winona, the Indian Girl Shot. Her departure allowed Annie Oakley to rejoin Cody’s show in time for another long tour of Europe.

The show became part of the Paris Exposition, staged to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution. Oakley became the sensation of Europe: She reportedly took part in the lighting ceremony of the newly built Eiffel Tower; the president of France offered her a commission in the French army; the king of Senegal wanted to buy her so she might kill the tigers then terrorizing his country; and she nearly created a scandal when she ignored protocol and shook hands with the Princess of Wales.

When

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

set up in Italy, Cody and Sitting Bull visited Rome on a tour personally conducted by Pope Leo XIII. To promote the show, an Indian village was built inside the Colosseum, and a mock shoot-out between cowboys and Indians was staged in St. Peter’s Square—followed by a sharpshooting demonstration from Annie Oakley. And the show’s concessionaires introduced another American creation to Italian audiences—popcorn!

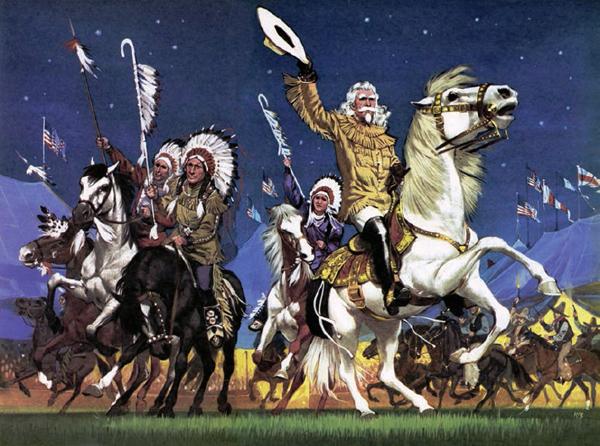

Buffalo Bill’s shows were wildly successful throughout Europe, creating the romanticized impression of the American West that has become accepted as reality.

While the show was wowing Europe, at home the United States Census Bureau officially declared the frontier settled. The dream of a nation stretching from ocean to ocean had come true. The Indian wars were over and most tribes were settled on reservations; the majority of the land had been explored and opened for settlement; the great buffalo herds were mostly gone; railroads crisscrossed the continent; and people were even talking to one another on the telephone. When Cody had first opened his show, it reflected current events, but within a

decade, it was presenting a sometimes nostalgic look at a rapidly vanishing era of our history. The reality had been transformed into myth. And crowds loved it. In 1890, the show drew six million people and reported a million-dollar profit. Buffalo Bill Cody and Annie Oakley had become among the best-known Americans in the world. Bill Cody was consulted by presidents on just about all matters concerning the West, and among his friends were the most celebrated writers, painters, and inventors of the time.

Producing a show of that size was an enormous undertaking and required ingenuity to set up and move quickly from place to place at minimal cost. In 1899, for example, the show gave 341 performances in 200 days across 11,000 miles. To accomplish that, the troupe had to carry its own bleacher seating and canopies, electrical generators, and kitchens, and under the direction of James Bailey of the Barnum & Bailey Circus, they revolutionized methods of rapidly and safely loading and unloading railway flatcars.

Among the people who delighted in the performance was the inventor of the electric light, Thomas Edison, who in fact did light the show brightly, enabling it to become one of the first entertainments to be staged in the relative coolness of the night. Oakley and Edison had met in Paris at the 1889 exposition, where he was demonstrating his phonograph. In 1894, he invited her to the Black Maria, which is what he called his photo studio, where he used his kinetograph, the earliest movie camera, to capture the smoke as she fired her guns—as well as visually recording glass balls shattering when she hit them. The “moving pictures” he shot eventually were shown in Kinetoscope parlors and cost five cents to view, causing these halls to become known as

nickelodeons

—and turning Annie Oakley into one of the world’s first “movie” stars. After proving he could capture rising smoke on film, Edison also brought Buffalo Bill and several Indians to his West Orange, New Jersey, studio and recorded them.

The success of the

Wild West Show

found Cody in the odd position of being the employer and, at times, the guardian of the same Indians whose tribes he had been at war with only years earlier. It is possible he had even fought some of these specific individuals in battle. But Buffalo Bill proved to be an enlightened employer, paying his cast equal wages and treating all of them—including Indians, black cowboys, and women—with great respect. Indians, in particular, earned a much better wage than would have been possible on a reservation and were able to make their case for fair treatment in show programs and when speaking to newspapers. Cody’s abolitionist upbringing transformed easily into common decency, and he was said to be respected by all the people he dealt with. He was known to be an advocate for women’s suffrage and at every opportunity fought for fair treatment of Native Americans.

Annie Oakley and Frank Butler had left the show at the beginning of the new century,

and Oakley once again took to the stage, starring as

The Western Girl,

a play written for her that involved her using a pistol, rifle, and rope to vanquish the bad guys. A story published in William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers in 1904 accused her of being addicted to cocaine and claimed she had been arrested. Outraged by that attack, she sued fifty-six newspapers for libel—winning fifty-five of those cases and restoring her reputation.

The Butlers never quite mastered the art of settling down: building then selling houses in several places, preferring to stay at resorts or in a New York City apartment. Annie Oakley was quoted as admitting, “I went all to pieces under the care of a home.” She retired from touring in 1913.

Toward the end of his life, Cody explained, “[T]he west of the old times, with its strong characters, its stern battles and its tremendous stretches of loneliness, can never be blotted from my mind.”

By then,

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

had lost its luster. Through the years, several others had attempted to launch competitive Wild West shows, although none of them had been able to survive more than a few seasons. But in 1903,

The Great Train Robbery,

the first Western motion picture, had been released. It was a huge success and further established the Western as a popular cultural form—and cut deeply into the audiences for live shows.

Buffalo Bill had earned a fortune bringing the Wild West to the East Coast and Europe. He’d invested those profits in everything from Arizona mines to filmmaking, publishing, and even a crazy idea about selling fresh spring water all over the country, but in the end, he had little money to show for it. In ’08, he’d sold a substantial interest in the show to

Pawnee Bill’s Wild West and Great Far East Show

but continued starring in it. In 1910, he began a three-year farewell tour, and the show finally closed forever in 1913.

Buffalo Bill immediately secured backing to produce a five-reel Western picture,

The Indian Wars.

He toured with other shows for another two years, until his health failed. When his death was reported, quite prematurely, he remarked, “I have yet a great life work to complete before I pass over the river. I have been supervising the taking of motion pictures. These start with the opening of the west …”

In 1915, Frank and Annie Butler drove their car to visit him while he was appearing in a show entitled

Sells Floto Circus & Buffalo Bill Himself

. That was the last time they were together. When he died at home in 1917, the nation mourned. As the respected western historian and writer William Lightfoot Visscher wrote, “Prominent men and women from many states and civilized nations journeyed to Denver to attend his funeral. Cities did him honor and legislatures adjourned for the obsequies …”

From Pine Ridge, the Oglala Sioux sent a telegram, part of which read, “Know that the Oglalas found in Buffalo Bill a warm and lasting friend; that our hearts are heavy from the burden of his passing …” It was signed

Chief Jack Red Cloud.

And Annie Oakley said simply, “He was the kindest hearted, broadest minded, simpliest [sic] most loyal man I ever knew. He was in very fact the personification of those sturdy and lovable qualities that really made the West …”

Annie Oakley continued to give occasional performances for charity and was especially active raising money to aid the war effort throughout World War I. A strong supporter of women’s suffrage, she offered to raise an entire regiment of women capable of fighting in that war. She was sixty-six years old when she died in November 1926, and only three weeks later, Frank Butler, her husband of fifty years, also died.

But both Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley have lived on in the legends they helped create.

Annie Oakley would be remembered in numerous movies, beginning with the 1935 film

Annie Oakley,

and most successfully in Irving Berlin’s Broadway musical and subsequent hit film

Annie Get Your Gun

; while the story of Buffalo Bill has been told in numerous entertainment formats, and he has been played by numerous actors, from Roy Rogers to Paul Newman.

Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley created the passion for western entertainment that remains so firmly embedded in American culture. Annie Oakley, for all her talent with a gun, never set foot in the Old West. William Cody, on the other hand, played an important role not only in settling the West but also in creating the myths that would end up at least partially obscuring what really happened in this exciting but dangerous time. It was his vision that laid the foundation for all the wonderful storytellers who would follow him, who would turn the hardest days in the Old West into one of the world’s most popular entertainment subjects.

While honoring Bill Cody, the state legislature of California properly noted, “[I]n his death that romantic and stirring chapter in our national history that began with Daniel Boone is forever closed.”

THE AMERICAN INDIAN: WITH NO RESERVATIONS

Lonesome Dove

author Larry McMurtry wrote, “Most of the traditions which we associate with the American West were invented by pulp writers, poster artists, impresarios and advertising men.” And without question, at the heart of that invention is the American Indian.

The Indians played an essential role in the actual settling of the West and then played an even larger role in all the glorified stories told about it. The actual relationship between the white settlers and the several hundred different tribes that had lived on the land for thousands of years is extraordinarily complex, but in the legends it generally has been described as an almost continuous battle between mostly innocent settlers wanting to live in peace and the warlike Indians who slaughtered them.