Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (27 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

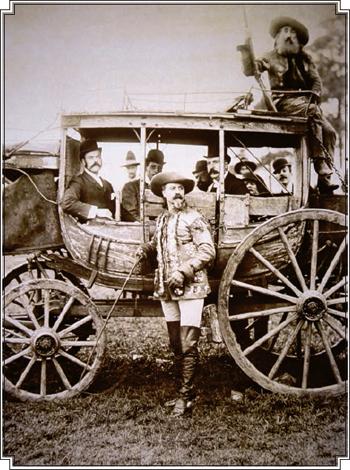

For more than three decades, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows thrilled America and Europe, as seen in this 1907 reenactment of a battle from the Indian wars.

Buffalo Bill responded, just as loudly, “I’ve held four kings, but four kings and the Prince of Wales makes a royal flush such as no man has ever held before!” And with a great wave of his hat, Bill Cody ended the show.

Some courageous men explored and settled the West, and other brave settlers fought the Native American warriors for the right to live there, but William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, with important assistance from Annie Oakley, Sitting Bull, and Geronimo, successfully merchandised it. For three decades, Buffalo Bill Cody’s

Wild West

brought the spirit and the adventure of life on the frontier to audiences around the world, successfully creating the romantic, rip-roaring image of the Old West that persists to this day. Presidents, kings, Queen Victoria, and Pope Leo XIII were all captivated by the action-packed performance.

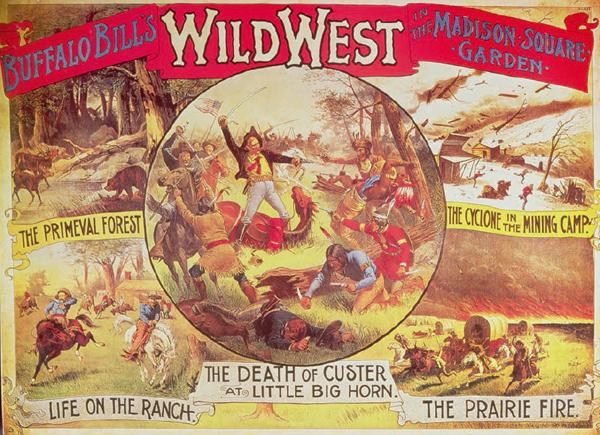

In addition to the Indian attack on the Deadwood stage—and Cody actually had purchased the old Deadwood stage for this scene—the show included, among many other entertainments, pioneers defending their homestead against an Indian attack; a stage or train robbery; Indians attacking a wagon train; races between Pony Express riders and between an Indian on foot and a pony; buffalo hunting; displays of roping and riding, bulldogging and sharpshooting; and even a sad reenactment of General Custer’s Last Stand. Buffalo Bill and his cast of hundreds of “authentic Red Indians” brought the Old West to life for tens of thousands of people and, in so doing, made himself the most famous American in the whole world.

The attempted robbery of the original Deadwood stage was a highlight of the show, and Cody would invite local dignitaries to participate as passengers.

While most people loved the show, few of them ever wondered how accurate it was—or whether Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley had ever played a real role in the Old West. Were those two legendary figures true survivors of a time gone by, or were they simply entertainers earning a fine living from the exploitation of a myth? Ironically, Buffalo Bill Cody is probably remembered more for the amazing shows he created than for his very real accomplishments riding the ranges of the West.

After a parade down Fifth Avenue, the

Wild West Show

settled into Madison Square Garden for the winter of 1886. As more than five thousand spectators—including General Sherman—watched on opening night, “One big bull elk forgot his cue, [and] sauntered slowly down the arena, inspecting the pretty girls in the boxes with critical stares and gazing at the rest of the spectators in a tired way.”

William Cody was born in rural Iowa in 1846 to educated parents. When he was seven years old, Isaac and Mary Ann Cody sold their farm and moved to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, arriving in the middle of the raging debate over slavery. In that part of the state, Isaac Cody’s antislavery sentiments were not popular, and eventually he was stabbed while giving an impassioned speech. He died a few years later while trying to bring antislavery settlers from Ohio into the state, leaving his family close to ruin. To support them, young Bill Cody took an assortment of jobs, including “boy extra” on wagon trains, teamster, bull whacker on cattle drives, and, finally, army scout. How he developed his renowned tracking and shooting skills isn’t known.

As he wrote in his autobiography,

Buffalo Bill’s Own Story,

his first encounter with Indians occurred while he was scouting for the army. Soldiers were trying to quash a threatened Mormon rebellion in Salt Lake City. “Presently the moon rose,” he wrote, “dead ahead of me; and painted boldly across its face was the figure of an Indian. He wore this war-bonnet of the Sioux, at his shoulder was a rifle pointed at someone in the river-bottom 30 feet below; in another second he would drop one of my friends. I raised my old muzzle-loader and fired. The figure collapsed, tumbled down the bank and landed with a splash in the water…. So began my career as an Indian fighter.”

Almost as if in preparation for the spectacular shows he would eventually produce, Cody had a range of real-life experiences in most of the situations his performers would later replicate. When out trapping with a friend, he had slipped and broken his leg; his friend left to get help to bring him home, and Cody was discovered by a band of Indians, who spared his life only because he was just a “papoose,” as he heard them describe him, and because he had previously met their leader, Chief Rain-in-the-Face. On another hunt, he ran across a band of murderous outlaws and was forced to shoot one of them to make his escape.

Bill Cody was only thirteen years old when he headed west to mine for gold but instead signed on with the Pony Express. After building and tending stations, he became one of the youngest riders on that trail—or, as he later would portray it, a lone figure dashing across the stormy prairies carrying the mail! In his autobiography, he claimed to have made the longest Pony Express journey ever, 322 miles round-trip. He also recalled, “Being jumped by a band of Sioux Indians … but it fortunately happened I was mounted on the fleetest horse belonging to the Express company…. Being cut off from retreat back to Horse Shoe, I put spurs to my horse, and lying flat on his back, kept straight for Sweetwater.”

It was while working as a rider that he began to gain fame as an Indian fighter. At one point, the Indians had become so troublesome that all service had to stop, so Cody joined Wild Bill Hickok and twenty or more other men to look for a horse herd that had been

stolen. They found the Indians, who had “never before been followed into their own country by white men,” camped by a river. Led by Hickok, they attacked, capturing not just their own horses but more than a hundred Indian ponies.

How many of these tales told by Cody in his bestselling autobiography are accurate will never be known, because so much is impossible to verify. But when it was originally published in 1879, his biographers believed that most of it was true, and none of the people he depicted ever contradicted his version of events.

At the beginning of the Civil War, he rode with Chandler’s Jayhawkers, an abolitionist militia that he joined happily to “retaliate upon the Missourians for the brutal manner in which they had treated and robbed my family.” He awoke one day and found himself enlisted in the Seventh Kansas Cavalry, although he claimed no memory of exactly how that happened. His most notable service was acting as a courier for Hickok, who was operating as a spy within the Confederate army, gathering important intelligence that affected the battles in Missouri.

After the war, Bill Cody continued scouting for the army, serving in ’67 as a guide for Brevet Major General George Custer, and later fighting the Plains tribes himself in many death-defying encounters. During this tour of duty, he took part in sixteen battles, including the 1869 fight against the Cheyennes at Summit Springs, Colorado. He fancied himself an expert Indian fighter, and in his autobiography he sometimes described braves he had killed as “good Indians.” The irony of that statement would be evident several years later. As his fame spread on the Plains, the army assigned him to work with Custer, guiding wealthy dignitaries on western hunting expeditions, mostly Europeans such as Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, who wanted the excitement of seeing a real wild Indian. For his service, in 1872 he became one of only four civilian scouts ever awarded the Medal of Honor, which, although not yet the rarely awarded medal it would become, was even then held in great esteem and given only to those who served with honor and valor.

In the late 1860s, he took up a challenge from a renowned scout and buffalo hunter named Billy Comstock to see which of them could kill the most buffalo in eight hours. This was another area of his expertise: In addition to scouting, he earned his living supplying buffalo to feed the crews building the Kansas Pacific Railway—a lot of buffalo. He once claimed he’d killed 4,280 head in seventeen months. The wager with Comstock was five hundred dollars. More than a hundred spectators turned out to see the contest. Using Lucretia, as he affectionately named his breech-loading Springfield rifle, he killed 69 to Comstock’s 46 and, in addition to winning the bet, became known from that day forward as the one and only Buffalo Bill.

By the time he had acquired that nickname, a young woman named Phoebe Ann Cates

was already astounding people with her uncanny marksmanship. Born in a rural Ohio cabin in 1860, she often said, “I was eight years old when I made my first shot,” describing shooting a squirrel in the head to preserve its meat for the stew pot. At the time, ladies of any age were not known for their marksmanship; in fact, most of them didn’t even shoot guns. Although “Annie” apparently could perform all the standard “womanly” tasks, such as cooking, sewing, and embroidering, she also could outshoot pretty much any man. As a teenager, she supported her family by selling game she had hunted and trapped to local hotels and restaurants, and she claimed she had earned enough to pay off the mortgage on the family farm.

While she was still a very young woman, one of her regular customers, enterprising Cincinnati hotel owner Jack Frost, arranged a one-hundred-dollar betting match between Frank E. Butler, the star and owner of the Baughman & Butler traveling marksmen show, and five-foot-tall Annie Cates. Through twenty-four rounds of live-bird trapshooting, they matched each other shot for shot, but after he missed his twenty-fifth shot, she successfully hit the bird and won the match. Rather than being upset about losing to a young girl, Frank Butler

fell in love with her. Within a year, she had become the star of Butler’s show and, at some point soon after, also became his wife. Their marriage lasted fifty years. It’s generally accepted that she adopted the name Oakley from the Cincinnati neighborhood in which they briefly lived.

Annie Oakley at work in 1892

Frank Butler understood the appeal of a small, lovely, and very feminine woman who could outshoot any he-man who challenged her, and he essentially retired to manage her career. Billing her as “Little Sure Shot,” he promoted her as the sharpest shooter in the world, “the peerless wing and rifle shot”—and routinely risked his life to prove it: Holding a lit cigarette between his lips, he would let her shoot it out of his mouth. Using a rifle, a shotgun, and a handgun, she could extinguish a candle at thirty paces, split a playing card facing her sideways from ninety feet away, hit dimes tossed into the air, and riddle dropped playing cards with numerous shots before they hit the ground.

For several years, they toured the new vaudeville circuit in an act that included their dog, who sat patiently and still and allowed Annie to shoot an apple off his head. In 1885, she accepted an offer to join the new

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

extravaganza, and within a year had become the second most popular performer in the show, second only to Buffalo Bill himself.