Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (23 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Although, according to the Cheyenne chief Two Moons, the battle at Little Bighorn lasted only “as long as it takes for a hungry man to eat his dinner,” it will forever be part of American folklore. The chaos of those brief moments was depicted by Charles M. Russell in his 1903 painting

The Custer Fight.

When Colonel Custer heard gunfire, indicating Reno’s troops had engaged the Indians, he turned in his saddle to face his men. “Courage, boys!” he yelled. “We’ve got them. We’ll finish them off and then go home to our station.” He did not know that Reno’s attack had failed.

Then he raised his hand in the air and began his charge into history.

Custer’s men were massacred. After forcing Reno to retreat, the main contingent of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors had turned to meet Custer. They surrounded his force and tightened the ring. Every soldier was killed, 210 men, and many of their bodies mutilated. There was no one left alive to report exactly what had happened. While the native peoples told the story from their point of view, their many versions were confused and contradictory. Countless historians have investigated and written about it, but the actual details of the battle will never be fully known. “Custer’s Last Stand,” as this worst defeat in American military history quickly became known, has become part of American mythology. Custer himself has become a historical enigma, as often praised for his courage in giving up his life for his country as he is vilified for his impetuousness in leading his men to slaughter. His name has become synonymous with defeat, and his actions that day have been cited as the ultimate example of hubris; his ego and ambition have been blamed for the decisions that resulted in the tragic loss of so many lives. Although several books published in the aftermath of the battle portrayed him as heroic, President U. S. Grant purportedly told a reporter for the

New York Herald,

“I regard Custer’s Massacre as a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself; that was wholly unnecessary—wholly unnecessary.”

Was Custer at fault, as Grant believed, for splitting his forces or for engaging the enemy without sufficient intelligence? Or, as many other people believe, was he betrayed by Major Reno and Captain Benteen, who were known to dislike him and were later accused of cowardice?

There is no question that George Armstrong Custer’s contributions to the victories in the Civil War and the Indian wars have been largely forgotten, and instead he is remembered almost exclusively for this devastating defeat. This is not the end that anyone would have expected.

George Custer was born in the small town of New Rumley, Ohio, in 1839. His father, a farmer and a blacksmith, belonged to the New Rumley Invincibles, the local militia, and often brought his son to their meetings. Dressed in a Daniel Boone outfit made for him by his mother, Autie (as he was called) loved the ceremony of those meetings, and by the time he was four he could execute the entire manual of arms—using a wooden stick. When war against Mexico was being debated in 1846, he stunned the corps of Invincibles by waving a small flag and declaring, “My voice for war!”

His passion for the military never wavered. Although, at that time, most of the cadets at the US Military Academy at West Point came from wealthy and well-connected families, Custer managed to convince a congressman to sponsor him for the Class of 1862. He managed to get into plenty of trouble at West Point. Each cadet was permitted 100 demerits every six months and, every six months, Cinnamon, as he was nicknamed because he would use sweet-smelling cinnamon oils on his unusually long blond hair, would manage to get close to that limit before the period ended and the clock started again. His infractions were always minor: He’d be late for supper, his long blond hair would be out of place, he’d swing his arms while marching, or he’d get into a snowball fight. His mischievous personality just couldn’t conform to the strict code of conduct. In his career at the Point he compiled 726 total demerits, which still ranks as one of the worst conduct records in Academy history. He was quite popular with his classmates, though. Once, in Spanish class, he asked the instructor how to say “Class dismissed” in Spanish. When the instructor replied, everybody stood up and walked out—another incident that helped him set that record.

Unfortunately, he wasn’t a good student, either. When the Civil War started in 1861, more than a third of his class dropped out to join the Confederacy. The rest of the class was graduated a year early to serve in the war—and academically he finished at the very bottom of the remaining thirty-four students. Ironically, he received his worst grades in Cavalry Tactics.

Few people would have predicted that a poor student who wouldn’t follow orders would soon distinguish himself on the battlefield, but as it turned out, George Custer proved to be a natural leader, a man of great courage, who—unlike many fellow officers—always rode at the front of his force when his men charged into battle. Those other officers might have found him arrogant and vain, but no one questioned his bravery.

When he graduated, he was offered a cushy and safe assignment or the opportunity to go right into combat. He chose to go to war; when he was told they didn’t have a mount for him, he managed to find his own horse. Second Lieutenant Custer joined the Second Cavalry in time to fight in the First Battle of Bull Run. He began distinguishing himself as a staff officer for General George McClellan during the Union army’s first attempt to capture the Confederate capital, Richmond. At one point during their march south, McClellan’s men were trying to find a safe place to cross the Chickahominy River, which was at flood tide. When Custer overheard General Joe Johnson complaining to his staff that he wished he knew how deep the river was, Custer, with typical bravado, spurred his horse into the middle of it, continuing even as the water rose up to his neck, then turned and announced, “This is how deep it is, General.” McClellan then assigned Custer to lead four companies of the Fourth Michigan Infantry into battle. Custer’s force captured fifty prisoners—and the first Rebel battle flag of the war. McClellan described Custer as “a reckless, gallant boy, undeterred by fatigue, unconscious of fear,” and promoted him to the rank of captain.

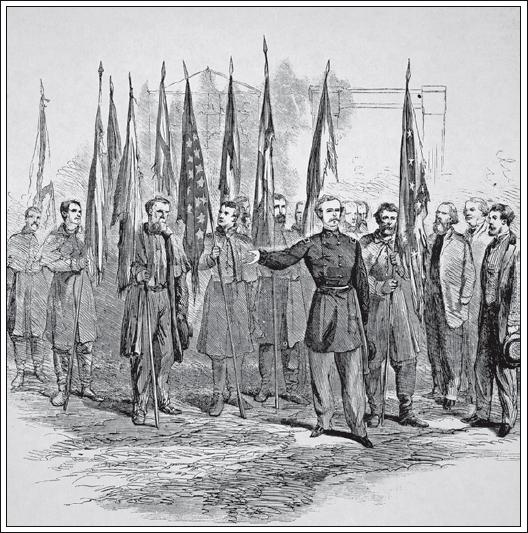

Custer distinguished himself in battle during the Civil War, and he is shown in this 1864 engraving presenting captured battle flags to the US war department.

Custer had learned the value of self-promotion and rarely hesitated to set himself apart from other officers. Following the example of his commander, General Alfred Pleasonton, he began wearing extravagant, customized uniforms. Cavalry captain James Kidd described him as “[a]n officer superbly mounted, who sat on his charger as if to the manor born.” He wore a black velvet jacket trimmed with gold lace and brass buttons, a wide-brimmed hat turned down on one side, a sword and belt, and gilt spurs on high-top boots. And around his neck was “a necktie of brilliant crimson tied in a graceful knot at the throat, the lower ends falling carelessly in front,” which stood out brightly against his blond mustache and flowing blond hair.

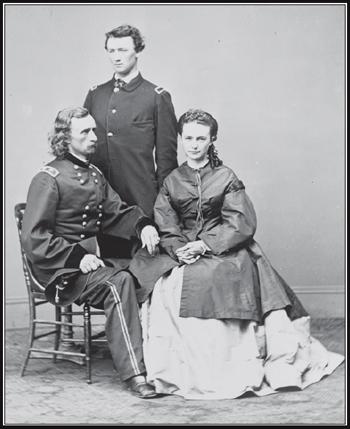

Known by his troops for wearing flamboyant uniforms, Custer posed for this 1865 portrait in the traditional Union blues.

Another officer wrote that Custer “is one of the funniest-looking beings you ever saw, and looks like a circus rider gone mad.”

Custer contended that there was a good reason for his choice of uniform. “I want my men to recognize me on any part of the field,” he wrote. And, given the smoke and confusion of close combat, that made a lot of sense. If initially turned off by his flamboyant style, his troops were won over by his aggressive tactics and his willingness to lead attacks. There are reports that he had as many as a dozen horses shot out from under him during the Civil War, proof that he was usually in the thick of the action. Eventually his men began wearing similar red kerchiefs as a matter of pride.

Throughout his career, however, Custer was criticized for his seemingly endless pursuit

of attention and recognition. At times, he would allow reporters to go out with his men on patrols. Some people believed that need for recognition caused him to behave recklessly.

It was at Gettysburg that George Custer became nationally famous. Three days before the battle began, he was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers, a temporary rank, and given command of the newly formed Michigan Brigade. At twenty-three years old, he was the youngest general in the army, but almost immediately, he showed his grit. At Hunterstown, on the road to Gettysburg, he led a charge into the mouth of Jeb Stuart’s troops. When his horse was shot and fell, he was nearly captured but was saved when a heroic private galloped forward and swooped him up, while at the same time shooting at least one Confederate soldier.

When Stuart attempted to flank the Union’s lines and attack the rear, he found Custer waiting for him at a place called Two Taverns. Ordered to counterattack, Custer stood before his troops, drew his saber, shouted “Come on, you Wolverines!” and raced into the action. He was said to be a veritable demon in the heat of battle, striking ceaselessly with any weapon available to him—slashing with his sword, firing his pistol—constantly urging his men forward, always forward. Within minutes, his horse was shot, but he commandeered a bugler’s horse and continued the fight. Seven hundred men clashed along a fence line, fighting for victory and their lives in close quarters. The sounds of battle were described as louder than a collision of giants; a relentless roar of men and horses, of carbines and pistols firing, of metal sabers clashing, and the cries of the wounded. And in the middle of it all was Custer. When he lost a second mount, he found another and never left the battlefield. His ability to stay in the middle of every fight without being wounded, even as one horse after the next was shot out from under him, became known far beyond his Wolverines as “Custer’s Luck.”

Finally Stuart withdrew; it was the first time in the war that his cavalry had been stopped. In his report, Custer wrote, “I challenge the annals of warfare to produce a more brilliant or successful charge of cavalry.” There were 254 Union casualties—219 of them were Custer’s men. Reporting Custer’s actions at Gettysburg, the

New York Herald

called him “the boy General with his flowing yellow curls.”

The public—and the newspapers—took notice. As Custer continued to distinguish himself throughout the remainder of the war, the media reported each success in increasingly larger headlines. His unusual manner of dress, his brilliant tactical maneuvers, his bravery, and the resulting victories made him great copy. Marching with General Philip Sheridan, Custer’s Third Division contributed to the victory in the 1864 Valley Campaign. In the battle of Yellow Tavern he led a saber charge into Jeb Stuart’s cannon, “advancing boldly,” he reported, “and when within 200 yards of the battery, charged it with a yell which spread terror before

them. Two pieces of cannon, two limbers … and a large number of prisoners were among the results of this charge.” Although he did not report it, supposedly his troops moved so quickly that they captured Jeb Stuart’s dinner.

Two weeks later, after the Wolverines had routed the Rebels at Haws Shop, an officer serving under Custer wrote in awe, “For all this Brigade has accomplished all praise is due to Gen. Custer. So brave a man I never saw and as competent as brave. Under him a man is ashamed to be cowardly. Under him our men can achieve wonders.”

Custer’s wedding in 1864 to Elizabeth Bacon, the daughter of a politically powerful judge, was a major social event attended by hundreds of prominent guests. Unlike most military wives, Libbie Custer became known for camping with her husband in the field whenever it was deemed safe, explaining years later, “It is infinitely worse to be left behind, a prey to all the horrors of imagining what may be happening to one we love.”