Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (18 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Legends (

from left

) Wild Bill Hickok, Texas Jack Omohundro, and Buffalo Bill Cody in an 1874 promotional photo for Cody’s show

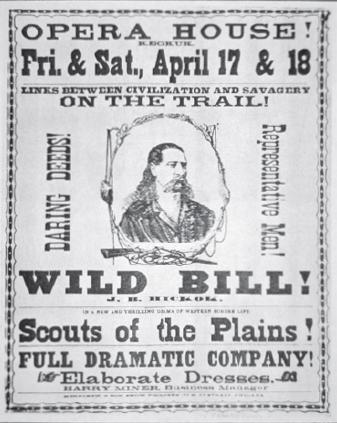

Scouts of the Plains

Hickok spent one winter performing in Cody’s show, and when he went back out west, Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro each gave him five hundred dollars and a pistol, urging him to “make good use of it among the Reds.”

Hickok apparently was terrible onstage. Worse, he knew it and was said to spend much of his time between performances presiding over a card game and a stream of liquor bottles. Legend has it that while the show was playing in New York City he walked into a poolroom to find a fair game. The players didn’t recognize him and began making fun of his long hair and western clothes. There was no one left standing when he walked out the door. Later he explained, “I got lost among the hostiles.”

Few doubt that Hickok could have spent the rest of his days trading on his fame, earning a living simply by showing up and telling his stories to awed crowds in the concert saloons and variety halls of the new entertainment called vaudeville. But that wasn’t right for him; he never quite embraced or fully accepted his celebrity. Perhaps that was due to his personality, which always chose action over words, or to his knowledge that so many of the tales written about him had been exaggerated or simply made up. He had accomplished a great deal, but no one could have done all the things with which he was credited.

Finally he could take it no more and left Cody’s show, going back out west where he belonged, eventually settling in Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 1876. His reasons for landing in Cheyenne aren’t known, but one may have been that Agnes Lake was staying there with

friends. It was the first time they’d seen each other since Abilene, though they had continued to correspond through the years. They took up quickly, though, and were married within months. The local newspaper noted, “Wild Bill of western fame has conquered numerous Indians, outlaws, bears and buffalos, but a charming widow has stolen the magic wand … he has shuffled off the coil of bachelorhood.”

Hickok still needed to figure out how to earn a living. His once-legendary eyesight appeared to be diminished and his bankroll was thin. Two years earlier, an expedition led by General Custer had discovered gold in the Dakotas, setting off a gold rush. Shortly after his marriage, Hickok gathered a group of men and set out for the Black Hills. Although people generally believe that he was going there to prospect, there also is the possibility that he was hoping to be hired on as marshal of the boomtown of Deadwood, giving him a chance to relive the great days of his life and to tame one last town.

Deadwood was no different than all the other towns that sprang up to support gold strikes. Money came hard, and the law was whatever the toughest men in town decided it was. Hickok mined during the day and played cards at night, trying to win enough of a stake to bring Agnes out there. He wrote to his new wife often, promising her, “We will have a home yet, then we will be so happy.” But there were also signs that he sensed real danger around him, and in his last letter to her he promised, “Agnes darling, if such should be we never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife, Agnes, and with wishes even for my enemies I will make the plunge and try to swim to the other shore.”

Some historians believe Hickok was resigned to his fate and had even predicted it, supposedly telling a friend, “I have a hunch that I am in my last camp and will never leave this gulch alive … something tells me my time is up. But where it is coming from I do not know.”

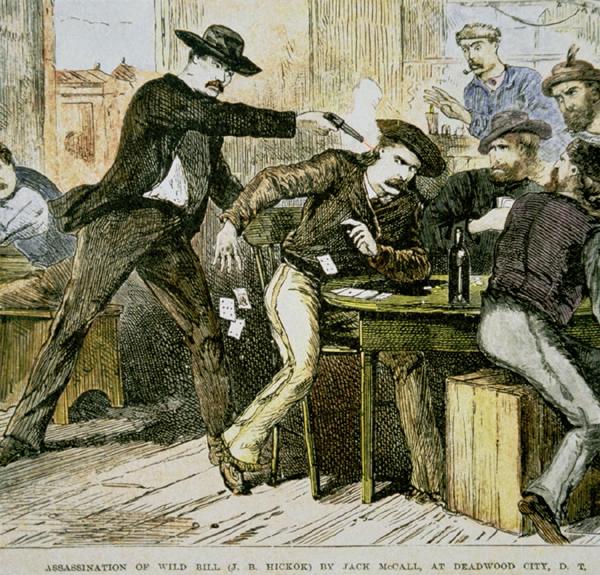

On August 2, 1876, Hickok strolled into Nutter and Mann’s Saloon, looking for a game of poker. Historians have speculated that he went to the saloon directly from a local opium den. Three men he knew were seated around a table, the only empty chair facing a wall. Hickok never sat with his back to a door; he wanted to see trouble when it walked in. Sitting in the available seat made it impossible for him to watch the rear entrance. He twice asked the other players to change seats with him, but both requests were refused. That these men felt comfortable turning down the great Hickok is an indication of how far his stock had fallen. Only a few years earlier, almost everyone would gladly have given up his seat for an opportunity to play cards with the famous Wild Bill Hickok. Reluctantly Hickok sat down in that chair and put his chips on the table.

The night before, he had played poker with a former buffalo hunter and gambler, Jack

McCall, known as Crooked Nose Jack; Hickok had cleaned him out, then offered him some money for breakfast. Some saw that as an insult. But McCall was back the next day, standing at the bar when Hickok walked into Nutter and Mann’s. If they acknowledged each other at all, no one ever spoke of it. Wild Bill’s game of five-card draw had been in progress for some time when McCall got up from his bar stool and walked past Hickok toward the back door—then stopped suddenly about three feet away from him and turned. Hickok had been winning and had just been dealt a pleasing hand—black aces and black eights. He had discarded his fifth card and was waiting for his next card—legend claims it was the jack of diamonds—when McCall suddenly pulled out his double-action Colt .45 six-shooter, shouted, “Damn you! Take that!” and fired one shot into the back of Hickok’s head at point-blank range. The bullet tore through his skull, emerging from his cheek and striking another player in the wrist. Wild Bill Hickok died instantly.

McCall reportedly pulled the trigger several more times, but his gun failed to fire. It was later determined that all six chambers were loaded, but only one bullet fired—the shot that killed Hickok. McCall raced outside and jumped on his horse, but his cinch was loose and the saddle slipped. He ran into a butcher’s shop, where he was quickly captured by the sheriff.

A satisfactory explanation for the assassination has never been found. McCall might have been avenging the “insult” from the previous night. But during his trial, he claimed that Hickok had killed his brother and he was avenging that shooting, although there is no evidence that he even had a brother. There were rumors that he had been paid to assassinate Hickok, and there is always the possibility that he simply wanted to kill the famous Wild Bill.

A trial was held in Deadwood the next day, and McCall, claiming he was entitled to avenge his brother’s death, was acquitted. The local newspaper derided the verdict, suggesting, “Should it ever be our misfortune to kill a man … we would simply ask that our trial may take place in some of the mining camps of these hills.”

McCall left town. When he reached Yankton, capital of the Dakota Territory, he was arrested once again. His acquittal in the first trial was set aside because Deadwood was not yet a legally recognized town. McCall was tried a second time—and during this trial it was suggested that he had been hired to commit the killing by gamblers who feared that Hickok, “a champion of law and order,” was about to be appointed town marshal. This time the jury convicted McCall, and he was sentenced to death. He was hanged on March 1, 1877.

The cards Wild Bill Hickok were holding when he was shot, black aces and eights, have been forever immortalized in poker lore as the famed “dead man’s hand.”

Since Hickok’s death almost one hundred fifty years ago, a question has remained

unanswered: Why did he agree to take a seat with his back to a door? No one will ever know for sure, but since that fateful day, many have wondered if Hickok was simply tired of life. In many ways, he had become a captive of his fame: Although he no longer was capable of living up to it, the great expectations remained. Wild Bill might well have moved to Deadwood, a wild place where reputations didn’t hold much water and where what mattered was only what happened yesterday, to escape his own legend. But on that fateful August day in 1876, it finally caught up with him.

During the assassin Jack McCall’s first trial, Hickok was described as a “shootist,” who “was quick in using the pistol and never missed his man, and had killed quite a number of persons in different parts of the country.”

At his death, he was credited with thirty-six righteous shootings. And his friend Captain Jack Crawford, who had scouted the trails of the Old West with him, probably described him best when he recalled, “He was loyal in his friendship, generous to a fault, and invariably espoused the cause of the weaker against the stronger one in a quarrel.”

UP AND DOWN TOWNS

As tens of thousands of settlers raced to find their fortunes in the West, countless boomtowns suddenly burst out of the sagebrush. Many of these towns, which usually were dirty, poorly built, and often lawless, existed for only a brief time, until the mines gave out, the cattle drives ended, or the railroad crews set down somewhere else; then they quickly became ghost towns. But whether a town struggled on or ceased to exist, the events that took place there—and their subsequent appearance in numerous movies and TV shows—made the names Dodge City, Deadwood, and Tombstone legendary.

Dodge City, Kansas, came into existence in 1871, when a rancher settled there to run his operation. Originally named Buffalo City, until someone discovered there already was a place by that name, it was perfectly located just a whisker west of Fort Dodge and near the Santa Fe Trail and Arkansas River. It boomed a year later, with the coming of the Santa Fe railroad and the opening of the first saloon. The railhead allowed cowboys to ship buffalo hides and, within a few years, longhorn cattle driven up on the Chisholm Trail from Texas to points north and east. Then they would stay awhile to brush off the trail dust and spend their earnings. “The streets of Dodge were lined with wagons,” wrote one city elder. “I have been to several mining camps where rich strikes had been made, but I never saw any town to equal Dodge.” “The Queen of the Cow Towns,” as it was called, offered a wide choice of saloons—including the famous Long

Branch—gambling dens, brothels, and even, for a brief period, a bullring. The hardest men in the West—cowboys off the trail, buffalo hunters, bull whackers, and muleteers—would ride in rich, ready for a good time, and ride out a few days later poor but happy. For a time, Dodge really was as wild as its legend. It welcomed more gunslingers than any other city, and

several of the great lawmen tried to calm it down, among them Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and Bill Tilghman. But it was actually the Kansas state legislature that caused Dodge’s demise, when it extended an existing cattle quarantine across the state in 1886 and shut down the end of the trail. With that, the fast money disappeared, and most of the population realized it was time to “get out of Dodge.”

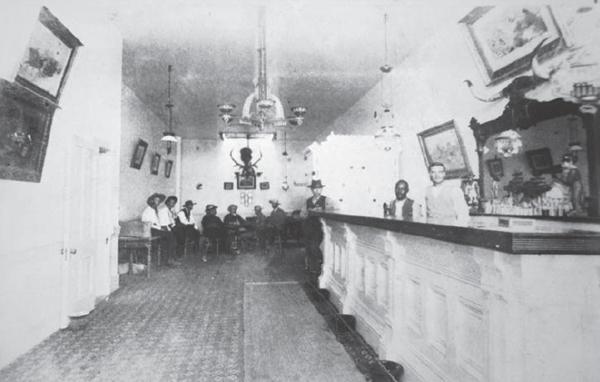

Dodge City’s Long Branch Saloon, which was built in 1874 and burned down in 1885, probably is best remembered as Miss Kitty’s place, where Marshal Matt Dillon would “set a spell” in the TV series

Gunsmoke.

The saloon was the center of entertainment in western towns. In addition to serving “firewater,” it might feature professional gamblers playing faro, Brag, three-card monte, poker, and dice games, or dancing, billiards, or even bowling. Many of them never closed, and a few didn’t even have a front door.