Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (17 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

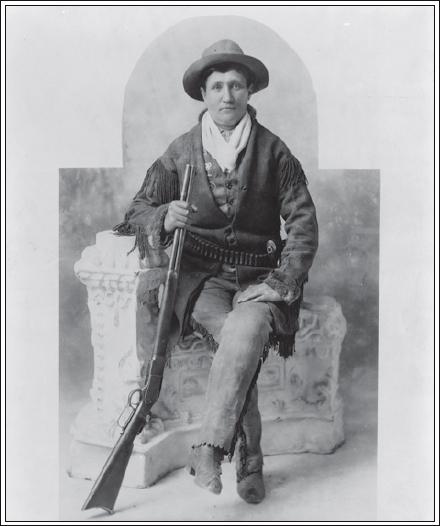

Martha Cannary, the fabled Calamity Jane, circa 1895

Strawhun went for his gun. Hickok was faster, drawing his Colts and putting two bullets into Strawhun’s head before he could pull the trigger. At the inquest, a jury determined that Hickok had been trying to restore peace and that his actions were justifiable. Although the local newspaper wrote, “Hays City under the guardian care of Wild Bill is quiet and doing well,” two killings in only a few months stirred the town, and in the next election Hickok was defeated by his own deputy, Peter Lanihan. Some questions about misconduct and irregularities were raised during the election.

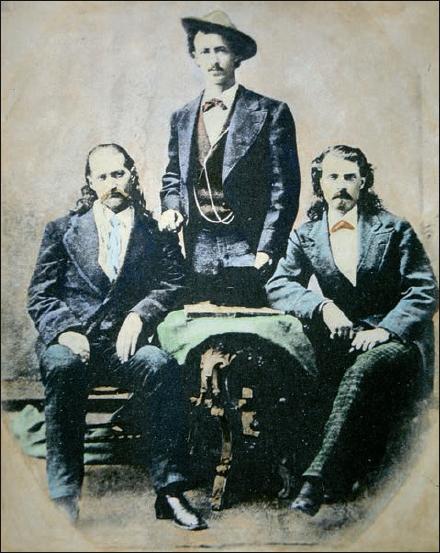

After that, Wild Bill drifted in and out of Hays City, sometimes working with Lanihan to enforce the law. From all reports, Hickok enjoyed all the delights of the place and could often be found sitting back against the wall at a poker table in one of its many saloons. He was also known to enjoy the company of the dance-hall girls, although stories that he dallied there with Martha Jane Cannary, who gained her own fame as the sharpshooting Calamity Jane, probably aren’t true. The two legends crossed paths in Hays City, but there is no evidence they ever were involved romantically.

Hickok’s stay in Hays City ended abruptly in July 1870, when he was confronted by Jeremiah Lonergan and John Kyle, two privates from Custer’s Seventh Cavalry. Animosity between Hickok and the troopers from Fort Hays had been building for a long time. Some of the veterans still resented the fact that Hickok had been paid as much as five dollars a day as a scout during the war while they were doing tougher duty and earning substantially less. More recently, it seemed as if every time they rode into town to blow off some steam, Hickok was waiting there to restrain them. With Lonergan, though, it was personal. His military career had been marked by both desertions and courage, and at some point he’d lost a tussle to Hickok. Lonergan and Kyle reportedly had been drinking the night they decided it was high time to deal with Wild Bill. Witnesses say Hickok was leaning against Tommy Drum’s bar, quite probably having enjoyed several whiskeys himself. The saloon was filled with other troops from Custer’s command when the two soldiers came in. Lonergan apparently came up behind him and, without one word of warning, grabbed hold of his arms and slammed him down to the floor. The two men wrestled, and when the fight turned in Hickok’s favor, Kyle pulled his .44 Remington pistol, put the barrel into Hickok’s ear, and squeezed the trigger.

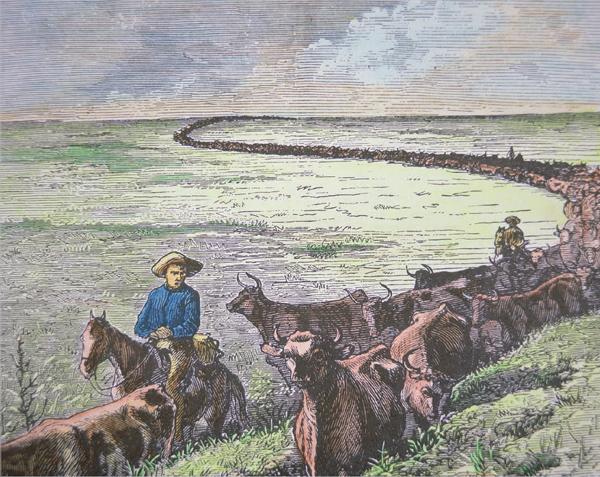

Longhorn cattle drive from Texas to Abilene, Kansas

The gun misfired.

Before Kyle could load a dry charge, Hickok managed to get one hand free, pulled out his Colt, and fired it, his first shot hitting Kyle in the wrist. Kyle’s gun clattered to the floor. Hickok fired again, this time striking Kyle in the stomach. As Kyle fell, mortally wounded, Wild Bill got off another shot, his bullet smashing into Lonergan’s knee; Lonergan screamed and rolled off Hickok. Wild Bill knew he had only seconds before other cavalrymen in the area heard about the fight and came to settle the score, so he scrambled to his feet and dived through the saloon’s glass window. He went back to his rented room to retrieve his Winchester rifle and at least one hundred rounds of ammunition. If a fight was coming, he was going to be ready for it. He walked up to Boot Hill, the cemetery and the highest point in the town, and took his position, waiting for them to come.

Fate had smiled on Wild Bill Hickok. This was the closest he had come to being killed in his career, and his life had been saved only because the black powder cartridges used by Kyle’s Remington were notorious for absorbing moisture, causing them to jam. Kyle was considerably less fortunate; he died in the post hospital the next day, joining the growing list of outlaws and troublemakers brought to final justice by Wild Bill Hickok. History records no legal hearings held about this matter, but clearly Wild Bill understood that Hays City was no longer a safe place for him.

Each of these tales was reported in the newspapers back east, where readers were riveted by the adventures of brave Americans taming the Wild West. The stories piled up as competing newspapers and the publishers of the popular dime novels fought for readers, and as a result Wild Bill Hickok became one of the best-known men in America. Some said he was even more famous than the president of the United States.

Hickok’s celebrity brought him to the attention of the town elders in Abilene, Kansas, known to be the rowdiest cow town in the West. Abilene had suddenly and unexpectedly found itself in need of a new marshal when Tom “Bear River” Smith was shot and nearly decapitated with an ax during a dispute with a local cattle rancher. For Hickok, Hays City was fine preparation for Abilene.

Abilene was the railhead at the end of the Chisholm Trail. Cowboys drove their herds all the way up from San Antonio, and from there the cattle were shipped back east. But it was a difficult place to pursue a civilized life. The citizens lived in fear each time a large herd arrived. The Texas cowboys, after months on the trail and with a payoff in their pockets, intended to have fun—and there were plenty of disreputable men and fancy women anxious to help them do it. Neither side was about to let the honest citizens stop them. So in April 1871, Abilene

mayor Joseph G. McCoy offered Hickok a badge and $150 a month, plus 25 percent of the fines received from the people Hickok arrested.

Hickok began by offering some strong advice to potential troublemakers: “Leave town on the eastbound train, the westbound train, or go North in the morning”—“North” meaning Boot Hill, and no one doubted his words. Hickok and his three deputies began cleaning up the town by closing down the houses of ill repute and warning the saloon keepers against employing card sharks and con men. He stood up to the bullies and the drunkards and enforced ordinances against carrying guns in town. He employed all the legal powers given to him, and if at times he found it necessary to exceed those boundaries, nobody much objected—and it didn’t seem that anyone defied him twice. Mayor McCoy once said, “He was the squarest [most honest] man I ever saw.”

As always, Hickok backed down from no man. Among the gunslingers who came to town was the outlaw John Wesley Hardin. While working along the Chisholm Trail, he supposedly killed seven men, and then between one and three more in Abilene, before Hickok pinned on the badge. Hickok finally confronted the eighteen-year-old Hardin—although at that time the marshal had no knowledge that he was a wanted man—and ordered him to hand over his guns for the duration of his stay in town. Many years later, Hardin bragged in his autobiography that he’d offered them to Hickok butt-end first and then, as the marshal moved to take them, employed the “road agents spin,” in which he twirled the guns in his own hands, ready to fire them. That statement is tough to believe, as that’s an old trick and Hickok certainly would have known about it, and Hardin never made the claim until long after Hickok’s death. The more likely story is that he simply handed them over.

At some point much later, while trying to get some shut-eye in his apartment at the American House Hotel, Hardin became irate because his roommate’s loud snoring was making that impossible—so he fired several shots through the wall into the next room to get the man’s attention. Unfortunately, one of those bullets hit the man in the head, killing him instantly. When Hickok responded to reports of gunfire in town, Hardin climbed out a window and hid in a haystack, later writing, “I believed that if Wild Bill found me in a defenseless condition he would take no explanation, but would kill me to add to his reputation.” Instead of standing up to the marshal, Hardin stole a horse and hightailed it out of town.

Hickok also found time to do some courting. Only a few months after he moved to Abilene, “the Hippo-Olympiad and Mammoth Circus,” starring the beautiful Agnes Thatcher Lake, came to town, and Hickok took up with the leading lady. Agnes Lake was a well-known dancer, tightrope walker, lion tamer, and horsewoman, who had toured Europe

and even spoke several languages. Wild Bill was smitten but was convinced that she would eventually return to the East Coast.

Until that time, another gal, Jessie Hazell, the proprietor of a popular brothel, had held his attention. But the “Veritable Vixen,” as the successful businesswoman was known in Abilene, instead had returned the affection of another suitor, Phil Coe. Coe was a gambler who coowned the Bull’s Head Tavern with gunfighter Ben Thompson. Even before their romantic competition, Hickok and Coe had built a strong dislike for each other. Not only had Hickok’s rules been bad for Coe’s business, but the marshal had embarrassed Coe by personally taking a paintbrush and covering the Bull’s Head’s finest advertisement: a painting of a bull with a large erect penis that adorned the side of the building. In response, Coe reportedly promised that he was going to kill Hickok “before the frost,” claiming that he was such a sure shot that he could “kill a crow on the wing.”

The famous story goes that when Hickok heard that, he replied, “Did the crow have a pistol? Was he shooting back? I will be.”

This feud finally erupted into gunplay on the cool night of October 5. It is generally agreed that Coe, who might have been drunk, announced his intentions by firing several shots into the air, in violation of the law. Hearing the shots, Hickok told his close friend and deputy, Mike Williams, to stay put while he investigated. Wild Bill found Coe and a large number of his supporters waiting for him in front of the Alamo Saloon. Coe told the marshal he’d fired at a stray dog. Hickok responded by ordering Coe and his men to hand over their guns and get out of town.

This was the moment Coe had been waiting for. Hickok was alone on a dark street, completely surrounded by men who hated him and his laws. Coe fired twice; both shots missed. Hickok returned the fire and he did not miss. Both shots hit Coe in the stomach.

Suddenly, from the corner of his eye, Wild Bill saw another man with a revolver charging at him out of the shadows. He whirled and fired twice more. The man went down in the dirt. It was probably only seconds later that Hickok realized that he’d killed his deputy, Mike Williams, who had heard the four shots and come running to stand with him.

Hickok turned on the mob, reportedly warning, “Do any of you fellows want the rest of these bullets?” They saw the anguish and the anger on his face and drifted away. Williams’s body was carried into the Alamo and laid on a billiard table. It was said that Hickok wept.

After that night, he was a changed man. He’d spent his life killing men who had deserved it, but this was different. He had reacted too quickly and his friend had paid the ultimate price. There were so many things Wild Bill Hickok was good at, but finding a way to forgive

himself was not among them. His anger had been unleashed; it seemed like he was out of control. Within months the town had turned on him; a newspaper editorial declared that “gallows and penitentiary are the places to tame such blood thirsty wretches as ‘Wild Bill.’” In December, Abilene relieved him of his duties, and Wild Bill Hickok rode out of town.

His prospects were limited. Because of his work, and that of others like him, the West had become considerably less wild. He’d worked his way out of a job. He returned to Springfield and set out to earn his keep gambling. Historians report that he drank too much and won too little. It was there that Buffalo Bill found him.

The one thing Hickok had left was his reputation. People would pay to see him—pay a lot. He had dipped his toe into show business earlier, partnering with Colonel Sidney Barnett of Niagara Falls, New York, to produce a show called

The Daring Buffalo Chase of the Plains

, but the buffalo did not like being roped and the show had failed. Meanwhile, the showbiz bug had bitten Buffalo Bill Cody, who was producing

Scouts of the Plains; or, On the Trail,

a precursor to his famous

Wild West Show.

He offered Hickok a fair salary to star in the show. Hickok had little choice but to accept the offer.