Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (19 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Deadwood, South Dakota, sprang up almost overnight after gold was discovered, first by General Custer in the Black Hills, then quickly by a miner in Deadwood Gulch in 1875. Because by treaty this was Indian land, the army tried to keep out the prospectors, so it took tough men to settle it. Fortunes were made, mostly by the saloon keepers, gamblers, opium dealers, and ladies of the evening, who had followed the gold diggers. Its reputation as a lawless town was sealed when Wild Bill Hickok was shot in the back of the head there in 1876, and for a while, Deadwood averaged one murder per day. Hickok and Calamity Jane had ridden in together as guards escorting a wagon train bringing prostitutes and gamblers from Cheyenne, and both of them were buried on Deadwood’s Boot Hill. Only three years later, in 1879, a massive fire destroyed almost three hundred buildings; by that time, new gold claims were pretty much played out, people were ready to move on to the next boomtown, and Deadwood settled down.

Miners pulled the modern-day equivalent of almost $1.5 billion in silver from the mines near Tombstone, Arizona, between 1877 and 1890, and within a few years, its population exploded, from about one hundred

to fourteen thousand. It got its name because its founder, Ed Schieffelin, had been warned that the Apaches didn’t cotton much to prospectors and that the only thing he’d find in the hills there was his own tombstone. For several years, there were few more dangerous towns on the frontier; “the town too tough to die,” as it was known, was close enough to the Mexican border for rustlers to use as their base of operations. Eventually there were more saloons, gambling houses, and brothels there than in any town in the

Southwest. When the Cowboys gang met the Earp brothers at the O.K. Corral, Tombstone’s place in history, and in the movies, was ensured.

After being founded in 1879 when silver was discovered nearby, in less than seven years, the town of Tombstone grew from one hundred people to fourteen thousand. An 1886 fire destroyed the expensive pumping plant, and the population dwindled to a few hundred, turning it into a ghost town. It exists today as a tourist destination, the once-wild city where the legendary gunfight at the O.K. Corral took place.

Numerous other violent boomtowns eventually became ghost towns. Canyon Diablo, Arizona, for example, was created when railroad workers had to wait for a bridge to be built, and within months fourteen saloons and ten gambling houses faced one another on Hell Street. The first sheriff was dead five hours after he pinned on his badge, and none of the five men who followed lived more than a month. When the bridge was finally completed ten years later, most people got on the train and left.

Gold was discovered in Bodie, California, in the Sierra Nevada in 1859, and before the vein dried up a decade later, the population had grown to ten thousand people. There is a long list of towns that boomed briefly, from Fort Griffin, Texas, to Leadville, Colorado (originally known as Slabville). However, throughout the country, it was believed that “the roughest, toughest town west of Chicago” was Palisades, Nevada, which had more than a thousand showdowns, bank robberies, and Indian raids in about three years in the mid-1870s. Although no one is quite sure how it began, each day as the railroad arrived, townspeople would stage a fake showdown or holdup and getaway for the benefit of the “dudes” from back east. Apparently this was done for entertainment rather than profit, as no money changed hands. The terrified passengers, who were never let in on the joke, would tell stories of their encounters with outlaws to newspapers back home. The stories were printed or otherwise passed along, allowing Palisades to gain its notorious reputation.

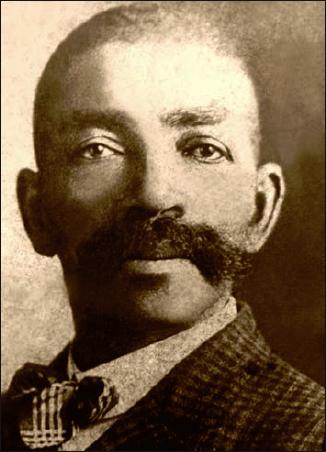

BASS REEVES

On Monday night, January 30, 1933, racing to the unmistakable beats of Rossini’s

William Tell

Overture, a new hero rode into American cultural history.

American families struggling through the Great Depression gathered around the radio every night for a few hours of escape and entertainment. On that winter’s night, they were introduced to a remarkable character who would take Americans with him on his adventures into the next century. In a mellifluous voice resonating with awe, the announcer introduced the Superman of the Old West:

A fiery horse, with a speed of light—a cloud of dust, a hearty laugh, The Lone Ranger is perhaps the most attractive figure ever to come out of the West. Through his daring, his riding, and his shooting, this mystery rider won the respect of the entire Golden Coast—the West of the old days, where every man carried his heart on his sleeve and only the fittest remained to make history. Many are the stories that are told by the lights of the Western campfire concerning this romantic figure. Some thought he was on the side of the outlaw, but many knew that he was a lone rider, dealing out justice to the law abiding citizenry. Though the Lone Ranger was known in seven states, he earned his greatest reputation in Texas. None knew where he came from and none knew where he went.

And then, as thunder boomed in the background, the story began: “Old Jeb Langworth lived alone in his small shack just outside the wide open community of Red Rock. One evening as he was watching the coffee boil and the bacon sizzle in the pan, and thinking of how snug his cabin was, with the storm raging outside, there came a knock on the door …”

A masked man riding the range with his trusty sidekick, the Indian brave Tonto, protecting the weak, righting wrongs, and dispensing Old West justice with his blazing guns, the Lone Ranger was the perfect hero.

No one knew his real name or where he came from, only that he left his calling card, a silver bullet, when he uttered his famous parting words, “Hi-Yo, Silver—away!” then disappeared into the wilderness until the next episode. The Lone Ranger eventually became one of the most iconic figures in American media, a star of radio, television, movies, novels, and comic books.

But what has been almost completely forgotten is that the character of the Lone Ranger was likely based on the life of a real person, whose true story is even more incredible than the fictitious adventures of the masked man.

Bass Reeves was a black American, born into slavery in Crawford County, Arkansas, in 1838, but came of age in Grayson, Texas. He was the property of William S. Reeves, but apparently early in his life was given to Reeves’s son George. While growing up, Bass Reeves never learned to read or write, but his mother taught him the Bible, and he was known to recite verses from memory. He was such a good marksman that his master entered him in shooting contests. When George Reeves eventually became the county sheriff and tax collector, he undoubtedly was pleased to have his sharpshooting servant at his side. Unfortunately, the history of black men in America around that time is difficult to reconstruct. Reeves would later claim to have fought in the Civil War battles of Chickamauga and Missionary Ridge under Colonel George Reeves and earned his freedom on the battlefield, but another story claims that he attacked his master when they argued over a card game and knocked him out, a crime punishable by death in Texas, so he was forced to flee into Indian Territory. Whatever the truth about his early years, Bass was twenty-two years old in 1863 when Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation and he became a freeman.

He eventually settled in the Indian Territory, which included present-day Oklahoma, and lived there peacefully among the tribes, the white squatters, and the white criminals escaping justice. He learned to speak the languages of “the five civilized tribes” (the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Seminoles, Creeks, and Cherokees) and gained a reputation as a skilled tracker, horseman, and deadeye shot—both right- and left-handed, and with both pistols and long guns. Bass Reeves was a big man, described as being six feet two and a muscular two hundred pounds, with a big, bushy mustache and piercing eyes that could a freeze a man before he made a foolhardy move. At first, as a freeman, he made his living working on farms, but his knowledge of the Territory “like a cook knows her kitchen,” as he once put it, enabled him to become a trusted guide and interpreter for the US marshals riding that range.

At the time, it was well known that “There is no God west of Fort Smith.” Indian Territory was one of the most dangerous places in the world. The murder rate rivaled that of the worst cities in the country; people were killed over anything from a horse to a coarse word. The outlaw Dick Glass once killed a man in a dispute over an ear of corn. It was once estimated that out of the twenty-two thousand white men living in the Territory, seventeen thousand were criminals on the lam. While tribal courts had jurisdiction over the Indians, white criminals had to be taken to Fort Smith, Arkansas, or Paris, Texas, for trial. The only law enforcement was the few US deputy marshals working out of Fort Smith. There often wasn’t a lawman to be found within two hundred miles, leaving plenty of room for vigilante justice.