Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (22 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

The case against Reeves pretty much fell apart when another witness testified that all those men actually had been chained in the prisoners’ tent at the time of the shooting and couldn’t have seen it happen. After deliberating for a full day, the jury found Reeves not guilty.

Although racism really wasn’t an issue during most of Reeves’s career, it ironically became important at the end of it. Judge Parker died in 1896, and two years later Reeves was transferred to Muskogee, in the Northern District of the federal court. He worked there until 1907, when Oklahoma was admitted to the Union and immediately instituted a series of harsh Jim Crow laws. Although these laws made Indians “honorary whites,” they were specifically designed to keep the races apart. That made it almost impossible for a black man such as Reeves to enforce the law on white people. Rather than retiring, the sixty-seven-year-old Bass Reeves joined the Muskogee police department and actually walked a beat—with the help of a cane—for two more years, until a lifetime of adventure caught up with him. He died in 1910, and as institutionalized racism became part of American culture, he was mostly lost to history. In fact, it isn’t even known where he is buried.

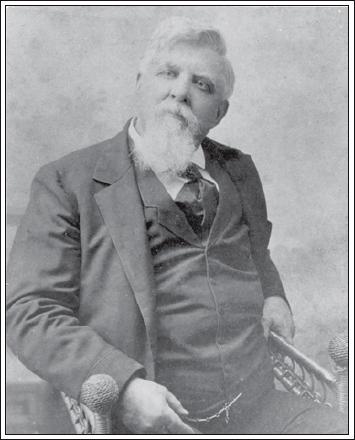

Judge Isaac Parker, shortly before his death in 1896.

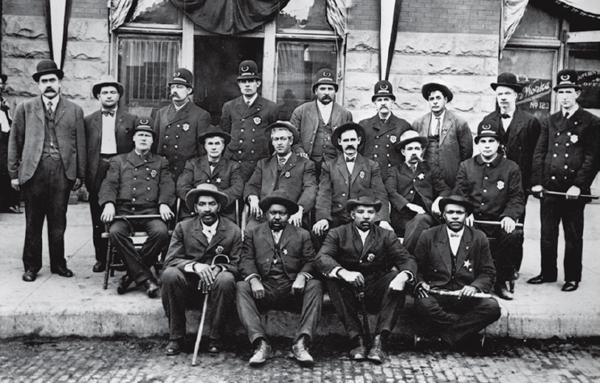

After Judge Parker’s death, Reeves transferred to Muskogee, in the Indian Territory, where this photo of federal marshals and local police officers was taken in about 1900.

As this country has begun recovering that history, the fact and legend of Bass Reeves has emerged. Did he serve as the model for the Lone Ranger? There is no specific evidence that he did, and the men credited with creating the character in 1933 never spoke about it. But the parallels between the real Bass Reeves and the fictional Lone Ranger are too strong to ignore. If the character was not based on Reeves, the coincidences would be almost as impossible to believe as the facts of Bass Reeves’s extraordinary life.

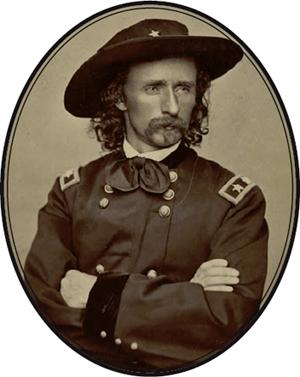

GEORGE ARMSTRONG CUSTER

On the hot sunny afternoon of June 25, 1876, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, his younger brother Tom Custer, and two other men brought their mounts to a halt atop the Crow’s Nest, a bluff above the Little Bighorn River in the Montana Territory. Custer raised his binoculars and looked into the distance—and what he saw must have taken his breath away. Nestled in a valley almost fifteen miles distant was the largest Indian encampment he had ever seen. He knew immediately that he had found Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. There was little visible activity in the village, leading Colonel Custer to believe he had caught them by surprise. That was an extraordinary bit of good luck. “We’ve caught them napping,” he said. He immediately sent a note to Captain Frederick Benteen, an experienced officer commanding a nearby battalion. “Come on,” the note read. “Big village. Be quick. Bring packs.”

Custer knew he had come upon the main Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux camp. One of his scouts reportedly told him, “General, I have been with these Indians for thirty years, and this is the largest village I have ever heard of.” Based on the best available intelligence, Custer assumed there would be no more than two thousand hostiles in the camp. His strategy was clear. As he had written just two years earlier in his well-received book,

My Life on the Plains,

“Indians contemplating a battle … are always anxious to have their women and children removed from all danger…. [T]heir necessary exposure in case of conflict, would operate as a powerful argument in favor of peace.”

Although his force of seven hundred troopers was outnumbered, it appeared that Custer intended to apply the same strategy he had previously used with great success: He would capture the Indian women, children, and elderly and use them as hostages and human shields. If his troops could occupy the village before the Indians organized their resistance, the warriors would be forced to surrender or shoot their own people. Initially, Custer planned to wait until the following morning to launch his attack, but when he received a report that hostiles had been seen on his trail, he feared losing the advantage of surprise. He had no way of knowing that those warriors had come out of the village and were riding away when they were spotted.

Had Custer waited through that night, it is quite possible that his scouts would have discovered the truth: What he had seen through his binoculars was only one end of a massive encampment that stretched for several miles along the river. Although the actual number of warriors has never been determined, it was many thousands more than he had estimated, and they were well armed with modern weaponry.

Custer split his force into three battalions. Major Marcus Reno’s second detachment was to lead the charge into the village from the south to create a diversion; then, while the hostiles rushed to meet this attack, Custer’s men would come down into the valley from the hills and take hostages. The Indians would be forced to kill their own families or surrender.

At noon, Custer ordered the attack to begin. Reno’s men crossed the Little Bighorn and charged—and were stunned to discover that the village was much larger than anyone had

realized. Hundreds of armed warriors, rather than dispersing as Custer believed they would, instead began fighting back. Reno had led his men into a trap. His charge was halted almost a mile from the village, and the Indians counterattacked his exposed flank with a force more than five times his. Furthermore, unlike his troops, most of whom were armed with single-shot rifles, many of the Indians carried repeaters. Reno was forced to fall back into the woods, telling his men, “All those who wish to make their escape take your pistols and follow me.” After holding there briefly, he led a chaotic retreat to the top of the bluff, losing about a third of his men, where he was reinforced by the three companies commanded by Captain Benteen. Their fortunate arrival may well have saved Reno’s troops from annihilation, but the combined forces were pinned down for crucial minutes in that position and could not move to help Custer.

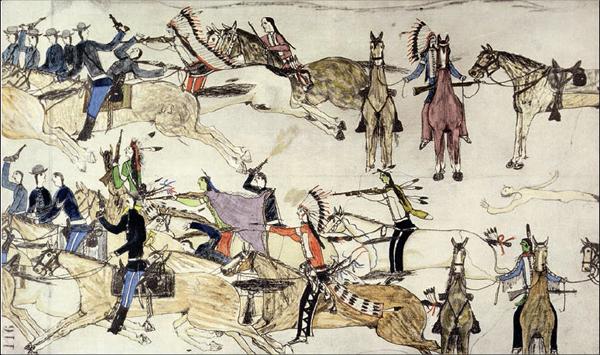

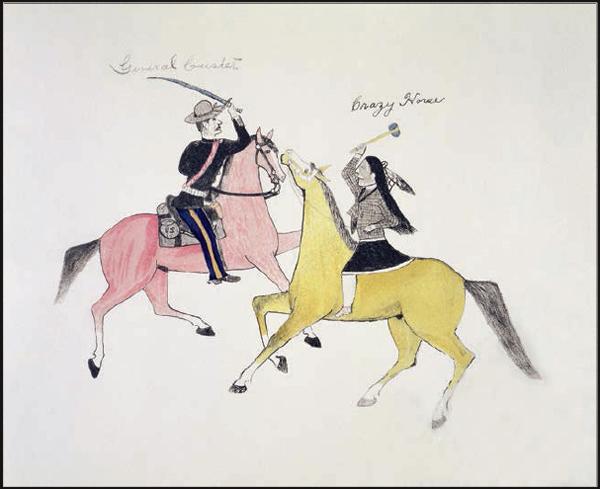

Custer expected the Indians to flee Major Reno’s diversionary attack. Instead, according to brave Flying Hawk, as seen in this illustration by Amos Bad Heart Buffalo, “The dust was thick and we could hardly see. We got right among the soldiers and killed a lot with our bows and arrows and tomahawks. Crazy Horse was ahead of all, and he killed a lot of them with his war club.”

When Custer first came upon the camp, it is probable that he envisioned an illustrious future. He was already a well-known soldier and Indian fighter, having been the youngest

brevet—or, temporarily appointed—brigadier general in the Union army at twenty-three years old. He had been present at Lee’s surrender at Appomattox and had later toured the South with President Andrew Johnson. This final victory over Crazy Horse in the Great Sioux War would raise his status to that of an American hero. He was hard on the path to glory. Even the presidency was possible.

Two great warriors, Colonel Custer and Crazy Horse, meet in this allegorical drawing by Kills Two.