Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (43 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

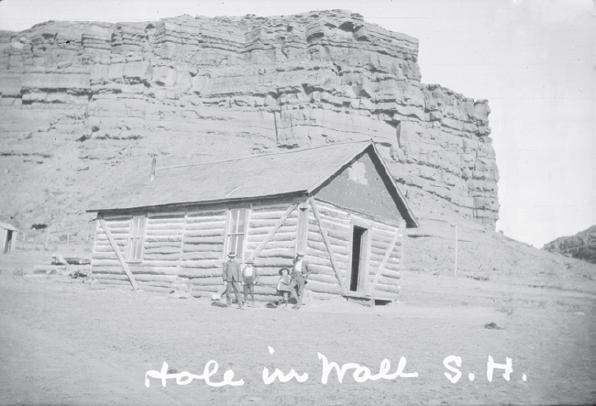

Only outlaws on the run were welcomed at the easily defended Hole-in-the-Wall in Wyoming and at Brown’s Park, or Brown’s Hole, in Colorado (

inset

).

Butch Cassidy was a new kind of bank robber. He treated robbing as his profession rather than as a dangerous hobby. Instead of just bursting into a place and waving guns around, he spent considerable time planning his jobs. Before proceeding, he gathered intelligence: By the time he was ready to move forward, he knew how he intended to get into and out of the town, how many lawmen might be on the job, and, most important, how much money was in the safe.

Even more crucial, he planned his escapes. For example, his men would climb poles and cut the town’s telegraph lines to prevent the sheriff from contacting nearby law enforcement for help. They would leave horses waiting a good distance from a town, and if they were pursued by a posse of lawmen, they would ride hard to that place and change mounts, so that they would be riding fresh horses while the posse’s would be wearing out. Sometimes all that planning wasn’t really necessary. In 1896, Cassidy, recently released after serving eighteen months of a two-year sentence for stealing a horse, learned along with Elzy Lay and Bob Meeks that the town of Montpelier, Idaho, had only a part-time deputy who was paid a paltry ten dollars a month—and that he had neither a horse nor a gun.

But the town did have a bank.

They rode out of Montpelier with $7,165 in cash, gold, and silver—a fortune at the time—pursued by part-time deputy sheriff Fred Cruikshank, frantically pedaling his bicycle. When the word of that job spread, seasoned bandits began offering to ride with Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch.

Sundance probably joined him right around that time. In April 1897, after cutting the telegraph wires in Castle Gate, Utah, the gang got away with the Pleasant Valley Coal Company’s $9,860 payroll. In response, the company paymaster handed out checks to miners, informing them, “Paymaster Cassidy of Robbers Roost will honor the paper.” As in almost all of Cassidy’s heists, no shots had been fired. Butch Cassidy wasn’t exactly nonviolent, but he definitely was averse to unnecessary bloodshed. He and his gang weren’t in the robbing business to hurt people, just the banks, the railroads, and the large cattle owners who were putting up fences across the once-open ranges. The most dangerous member of the gang was Kid Curry, who was described by the

Anaconda Standard

as being “fond of dress and his taste in that direction is rather flashy. He is absolutely reckless and careless, and since he has been an outlaw has been known to take the most desperate chances…. A dead shot with a revolver and rifle, he will be a hard man to capture.”

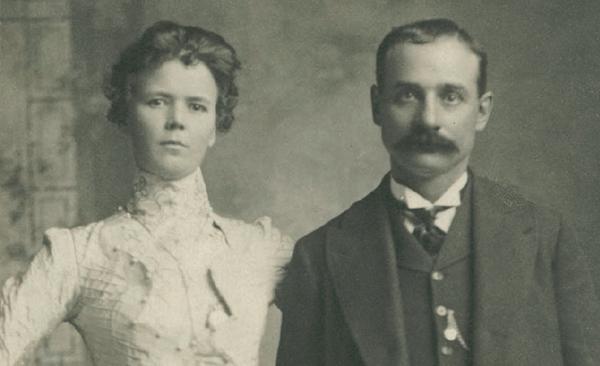

The “wildest of the Wild Bunch” was Harvey Logan, known as Kid Curry, who was credited with killing eleven men. He is shown here with his girlfriend, prostitute Annie Rogers, also known as Della Moore.

With each successful Wild Bunch robbery, Butch Cassidy’s reputation spread. In 1898, a Chicago newspaper declared him “King of the Bandits,” reporting that he was “the worst man” in Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Idaho. The article claimed that he had five hundred outlaws working for him, “subdivided into five gangs.” The daring exploits and well-planned heists of the Wild Bunch made headlines and sold newspapers throughout the country. The gang did give newspapermen plenty to write about: They were committing crimes in five states, the named four plus South Dakota, in robberies that netted as much as seventy thousand dollars.

Although the size of the gang was obviously exaggerated, the “King of the Bandits” story was accurate on one important point: Butch did run the operation. He was known for teaching the other outlaws the proper way to plan and carry out a job and was the acknowledged mastermind behind many of the robberies—even if he didn’t personally participate in them. Occasionally, something would go wrong. In July 1899, Elzy Lay was riding with a group of train robbers known as the Ketchum Gang. They held up the Colorado & Southern number 1

train outside Folsom, New Mexico, getting away with fifty thousand dollars. They didn’t get far, though; the railroads had gotten a lot smarter and were hiring their own guns for protection. The Ketchum Gang was surprised by a determined posse, which lit out after it. They tracked it for several days, and in the running gun battles, two members of the posse were killed, including sheriff Edward Farr, and one man was wounded. One of the bandits died of his wounds, another man escaped, and Elzy Lay was wounded and captured. He recovered well enough to spend the rest of his life in prison.

The loss of his best friend left an empty saddle next to Butch Cassidy, and the Sundance Kid stepped up to fill it. For a time after Lay’s incarceration, Butch Cassidy softened and considered leaving the profession. There are reports that he tried to make a deal with the railroads: If they agreed to let him be, he would leave their safes alone. He might even agree to consult for them as a security specialist—preventing train robberies. Any possibility of that deal ended near Wilcox, Wyoming, when the Wild Bunch took an estimated thirty thousand dollars in gold, cash, jewelry, and banknotes from the Union Pacific Overland Flyer number 1 train. According to a message sent by Union Pacific executives to the Laramie County sheriff, “[A] party of six masked robbers held up the first section of train number one … and after dynamiting bridges, mail and express cars and robbing the latter, disappeared.” There is some evidence that this robbery served as the inspiration for the famous 1903 silent moving picture,

The Great Train Robbery,

and later for a memorable scene in the 1969 classic film

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

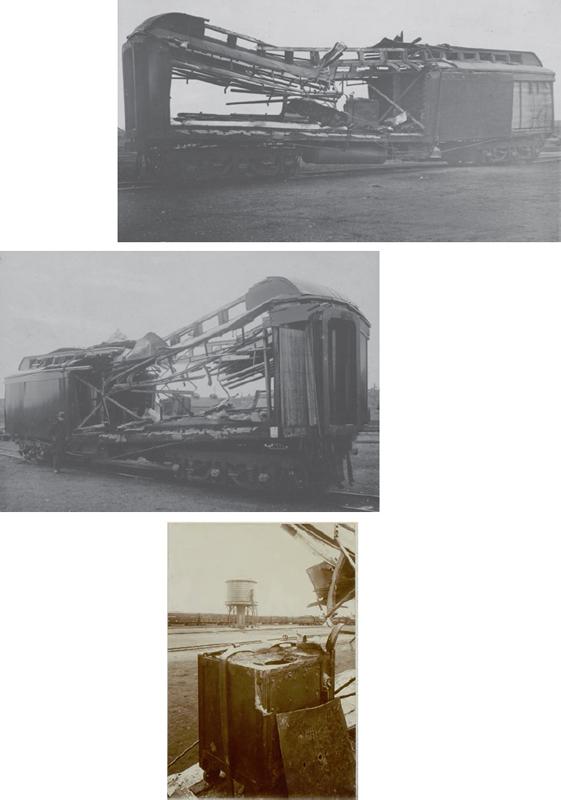

Blowing things up proved to be a bit of a problem for the gang. It turned out that the use of dynamite wasn’t one of their areas of expertise. Because no crew member aboard this train was given the combination to the safe carried in the baggage car, the outlaws reacted by attempting to blow it open. Apparently they used considerably more dynamite than was necessary, blowing up the entire railway car, down to the frame. Some of the money was scorched in the explosion or stained by raspberries, also being transported in that car. Thus, the Wilcox robbery might be considered a failed experiment. As the

Rawlins Semi-Weekly Republican

reported, the robbers “wrecked the car, blowing the roof off and sides out, portions of the car being blown 150 yards.” The safe, according to the

Laramie Daily Boomerang,

was blown “out of all semblance to the original self.”

After the robbery, members of the train crew complimented the manners of the thieves, one of them telling reporters that he had asked for a chew of tobacco, which was given to him by one of the robbers. Another crew member said the bandits had reassured him, “Now boys, don’t get scared. You’re just as safe here as you would be in Cheyenne.”

The robbers split up to make their getaway. Posses eventually including several hundred men, some of them using bloodhounds brought in all the way from Beatrice, Nebraska, for the task, pursued the bandits for several weeks. Converse County sheriff Josiah Hazen’s posse eventually caught up to Sundance, Kid Curry Logan, and Flat Nose Currie near Castle Creek, Wyoming, and in a gunfight, Kid Curry shot and killed the sheriff. As the

Boomerang

related, “It was rough and broken country, and the outlaws had the advantage of knowing every inch of it. From behind boulder and brushwood they held off the posse—five men against two hundred. Hazen exposed himself and the next moment reeled back with a bullet through his heart. Darkness fell …” Eventually the bandits escaped into Hole-in-the-Wall territory.

A classic scene from the movie

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

recreated the 1899 robbery of the Union Pacific Overland Flyer near Wilcox, Wyoming: Attempting to blow open the safe, the gang mistakenly used enough dynamite to blow up the entire railroad car.

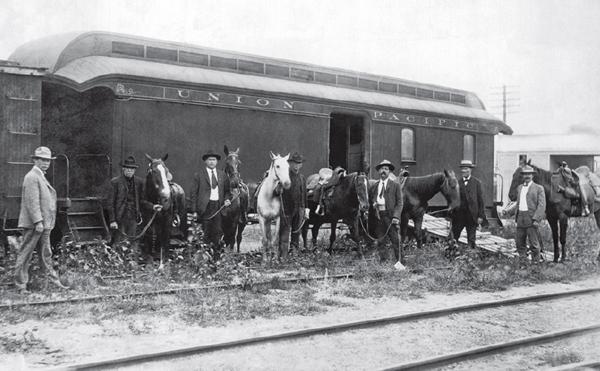

In an attempt to catch the Wild Bunch, the Union Pacific created a special car for mounted rangers and their horses, enabling them to instantly pursue the robbers.

The

New York Herald

reported, “They were lawless men who have lived long in the crags and become like eagles.” Although in fact these were killers and robbers, people had already begun romanticizing the Wild Bunch. But this robbery put a quick stop to that.

Killing the sheriff and stealing gold that was to be used to pay American boys fighting in the Spanish-American War proved to be the beginning of the gang’s downfall. The Union Pacific offered an eighteen-thousand-dollar bounty for the capture of the outlaws—dead or alive. It also

hired armed guards, Rangers, to protect their trains, warning, “They ride on the engine. In the baggage car, on the dry coaches, or in the sleepers, being instructed not to stay always at one point of the train. Any gang of bandits attacking a Union Pacific train now will know it has to reckon on a stiff fight, for not only is each train guarded, but somewhere up or down the line is the patrol body of rangers, ready to be shipped to the danger zone as fast as steam can carry them.”

Equally significant, the railroad also hired the Pinkertons to once and for all put the gang out of the stealing business. The Pinks represented the largest and toughest private security company in America. In fact, the Pinkerton agency was the only truly national law-enforcement operation; by the 1870s, there were more Pinkerton men than there were soldiers in the American army. They were known to be relentless in their pursuit, professional and thorough in their investigations, and as tough as necessary in their enforcement methods. Without question, they brought scientific detection techniques to American law enforcement, and they were the first to employ mug shots, fingerprints, and undercover agents. But they also were well known to rely on their own interpretation of the law to accomplish their objectives—even when it required bloodshed.

Following the Wilcox robbery, the Pinkertons picked up the trail of the Wild Bunch. And once they had it, they never let it go. By tracing scorched and stained banknotes, they tracked Kid Curry’s brother, Lonnie Logan, and Bob Lee to Cripple Creek, Colorado. Lee eventually was captured and sentenced to ten years in prison. Pinkerton operatives caught

up with Lonnie Logan in a rural farmhouse, and when he attempted to escape into the nearby woods, they shot him dead. Almost two years later, Pinkertons caught Kid Curry in Knoxville, Tennessee. After a trial, he was sentenced to 20 to 130 years in federal prison. He escaped less than a year later. In 1904, a posse caught up with him again after a train robbery near Parachute, Colorado. He was wounded in the shoot-out, and rather than surrender and be sent back to prison, he shouted to his companions, “I’m hit! Don’t wait for me, boys. I’m all in. Good-bye!” Then he put his gun to his head and committed suicide.