Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (42 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Butch Cassidy slowly pulled back a corner of the white lace curtain and looked out the broken windowpane. The plaza seemed deserted. But from behind every barrier, he saw the long barrel of a rifle pointed directly at him. Without counting, he figured at least three dozen Bolivian soldiers were drawing a bead on the house at that very moment. From the back of the darkened room, the wounded Sundance Kid asked evenly, “So, what do you think?”

“Looks like rain,” Butch replied casually. “Now’s probably not a good time to go for a stroll.”

“Yeah, that’s just what I was thinking.” After a brief pause, Sundance said, “Hey, I got an idea; when it clears up, let’s go watch one of those newfangled moving pictures.”

Butch sparked at that thought, then smiled broadly. “Hey, maybe they’ll make one of them about us sometime. You know, the story of two good-natured fellas just trying to make a decent living in a quick-changing world?”

Sundance laughed. “More likely, people’ll be walking on the moon.”

And then another shot shattered the remains of the window.

Did that conversation ever take place? Of course not. But it may be about as accurate as most of the stories that have been told about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and the gang they rode with, the Wild Bunch. Those oft-told tales, culminating in the award-winning 1969 film starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, have ensured that the two robbers and the last gang to roam the Old West will live forever in American folklore. Although the movie purportedly told the “true story” of these outlaws, in this case, the word

true

was defined pretty loosely.

According to that history, after a successful life of crime in the United States, Butch and Sundance fled to South America, where they were eventually trapped by soldiers in a small house in San Vicente, Bolivia. The ambiguous ending of that classic movie left open the possibility that Butch and Sundance somehow managed to survive that last gunfight. And, in the century since that 1908 shoot-out, several intriguing stories would actually seem to support that contention. Although the fate of all the other

members of the Wild Bunch is well known and accepted without question, some people do wonder if it is possible that Butch and Sundance somehow escaped.

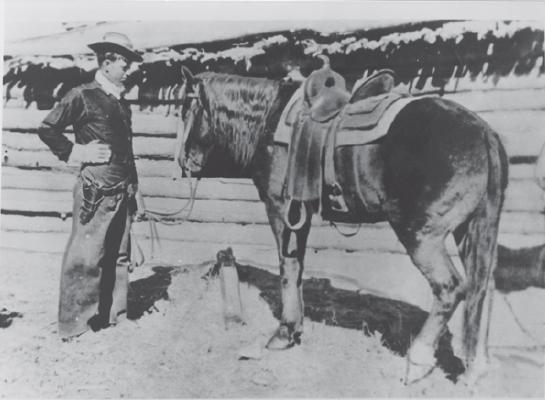

Robert Leroy Parker was born in April 1866, the first of thirteen children, and grew up in Circleville, Utah. As a teenager, he worked briefly as a butcher, supposedly cutting up rustled cattle, then rode for a time with rancher and cattle and horse thief Mike Cassidy, which led to him being nicknamed Butch Cassidy.

Harry Alonzo Longabaugh was born a year later in Mont Clare, Pennsylvania. As a twenty-year-old, he was caught stealing a gun, a horse, and a saddle from a ranch in Sundance, Wyoming. While serving eighteen months in jail there, he picked up the nickname by which he gained fame, “the Sundance Kid.”

A loosely knit association of various gangs, operating mostly out of the Hole-in-the-Wall hideout in Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains, the Wild Bunch pulled off the longest string of bank and train robberies in American history. In addition to Butch and Sundance, the primary members included Elzy Lay, Kid Curry Logan, News Carver, Tall Texan Kilpatrick, Matt Warner, Butch’s brother Dan Parker, Flat Nose Currie, and Harry Bass. From 1889 through the turn of the century, the Wild Bunch purportedly stole the modern-day equivalent of about $2.5 million, before each of its members was caught or killed, one by one.

Robert Leroy Parker, who became the famed Butch Cassidy.

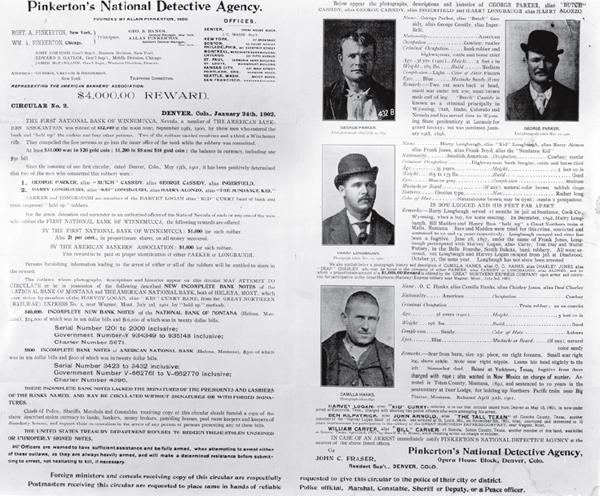

After Butch and Sundance held up the First National Bank of Winnemucca, Nevada, and got away with $32,640, the Pinkertons issued this Wanted poster, in which Cassidy was described as a “known criminal in Wyoming, Utah, Idaho, Colorado and Nevada,” and it was pointed out that the Kid “is bow-legged and his feet far apart.”

Butch Cassidy committed his first bank job in 1889, when he and several other masked men held up the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride, Colorado, riding away with about twenty thousand dollars. It was a transitional time for a region once known as the Wild West. Civilization was encroaching quickly, brought in by the 164,000 miles of railroad track that now stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, with trains that ran on a schedule. People were talking to friends miles away on the candlestick telephone. They were driving crazy fast in horseless carriages; in fact, only a year earlier, one of them had raced from Green Bay to Madison, Wisconsin, in just thirty-three hours, almost as fast as the stage. In cities, people were speeding over paved streets on bicycles with pneumatic tires. And instead of living in fear of Indians and highwaymen, for only a few cents people could watch reenactments of Indian attacks on wagon trains and stagecoach robberies—and even behold the actual Sitting Bull and twenty of his warriors, when

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

and its “Congress of Rough Riders of the World,” just back from Paris, came to town.

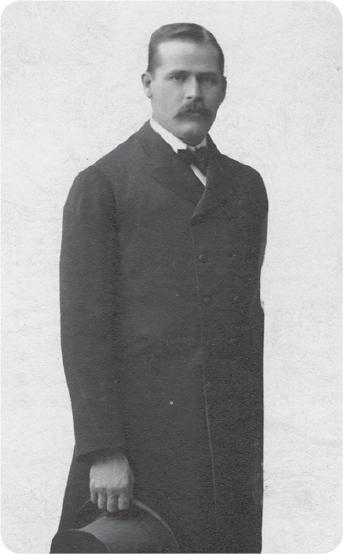

A 1901 formal portrait of Sundance taken in New York City

It took a while for Butch and Sundance to meet up, and by the time they did, both of them were fiercely committed to a life of larceny. Butch Cassidy had no formal education, learning the necessities of his trade from outlaw Mike Cassidy. By the time Mike Cassidy had killed a Wyoming rancher and taken off for parts unknown, Bob Parker could outride a posse and shoot well enough to hit a playing card dead center at fifty paces. It was said that he could ride around a tree trunk full tilt and put all six shots from his revolver into a three-inch

circle. But in addition to outlaw skills, he also was said to have a pleasing way with words, a sense of fairness, and a quick wit. His first train robbery took place outside Grand Junction, Colorado, when his gang forced the Denver and Rio Grande Express to stop by blocking the tracks with a small mountain of stones. Guns drawn, the gang climbed aboard and ordered the guard to open the safe. He refused, claiming he did not have the combination. Butch’s partner in that crime, a gunman named Bill McCarty, put his revolver to the guard’s head, cocked it, and asked, “Should we kill him?”

After a pause, Butch suggested, “Let’s vote!” He then persuaded the rest of the bandits to leave the guard alone. They collected about one hundred forty dollars from the passengers and rode away.

That wicked sense of humor was also present when he robbed the First National Bank of Denver. He approached the president of that institution and blurted out breathlessly, “Sir! I just overheard a plot to rob this bank!”

The bank president froze in his tracks. “Oh, Lord!” he supposedly said. “How did you learn of this plot?”

Cassidy smiled. “I planned it. Put up your hands!”

Sundance had spent several years working as a ranch hand, committing the occasional crime, when he joined Bill Madden and Henry Bass and held up the Great Northern westbound number 23 train near Malta, Montana, in 1892. This robbery was even less successful than Cassidy’s attempt: Although he got away with about twenty-five dollars, his accomplices were caught and implicated him. Within days, the railroad issued Wanted posters bearing an accurate description of him and offering a five-hundred-dollar reward for his capture. A similar Wanted poster issued years later described his nose as “rather long,” his hair as “brown, may be dyed, combs it pompadour,” and notes that he “is bow-legged and his feet far apart.” Madden was sentenced to ten years, Bass got fourteen, and Sundance spent the rest of his life as a fugitive.

It isn’t known precisely when or how Butch and Sundance met, but in those days, after pulling a job, desperadoes were known to retreat to hideouts until things cooled down. As the

St. George Union

wrote in 1897, “The outlaws live among ‘breakes,’ the wildest, most rugged and inaccessible except to the initiated anywhere under the blue firmament. In recesses cut into the side of those yawning chasms, two or three men are able to hold an army at bay. To such places all who have stolen, robbed or murdered are welcomed so that the gangs are becoming augmented steadily as time goes on … There is no use attempting to dislodge them by force … the only way would be to starve them out and it is questionable if that is feasible.”

These places had many advantages: They offered a clear view of all approaches, they were hard to find and get into, and if it became necessary, they were easy to defend. Pretty much anyone on the run was welcome in these hideouts. For example, young Bob Parker allegedly spent a lot of time in Brown’s Park (or Brown’s Hole, as it also was known), an isolated valley along the Green River, stretching between Colorado and Utah, when he was riding with Mike Cassidy. The Wild Bunch, or, as it originally was called, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, was formed by Butch Cassidy and his best friend at that time, rustler and holdup man Elzy Lay, while they were lying low in Robbers Roost, a hideout in southeastern Utah. (The gang also called itself, with a wink, the Train Robbers Syndicate.) When lawmen discovered the location of the Roost, the Wild Bunch departed for the famous Hole-in-the-Wall, a natural fortress atop a plateau in Carbon County, Wyoming, used by numerous gangs, a redoubt that could be reached only by squeezing through narrow passes and which was said to be so secure that a dozen men could defend it against a hundred.

Many plans were hatched and relationships formed along the well-known “outlaw trail.” Membership in a gang was fluid; people would ride with several other bandits for a limited time or for a specific job, then move along. Several dozen men participated in at least one of the more than two dozen holdups believed to have been committed by the Wild Bunch. It’s likely that Butch and Sundance crossed paths during one of these robberies.

By the turn of the twentieth century, it was becoming difficult to make a decent living cattle rustling or horse thieving, but it was a good time to be a bank or train robber. The West

was being tamed. New towns were springing up all over the prairie; most of them had banks, while few of them could afford sufficient law enforcement. The iron horse was replacing the stagecoach, carrying money and mail vast distances, often with very little security on board.