Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere (2 page)

Read Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere Online

Authors: Ravi Venkatesan

The military term

VUCA

means operating in an environment characterized by extreme volatility, uncertainty,

complexity, and ambiguity. This term describes well the business environment in India;

it should be spelled VUCCA, though, with the addition of another C for corruption.

Interestingly, while India is a VUCCA market, it also represents most other emerging

markets. Many countries, especially in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, resemble chaotic

India far more than they do centrally directed and efficient China (see

figures 1-2

,

1-3

, and

1-4

).

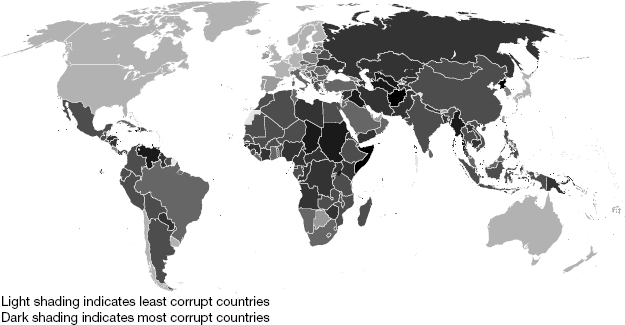

Take corruption; at number 95, India is in the middle of the pack of emerging markets

(see

figure 1-2

). Doing business in these markets means multinational companies have to figure out

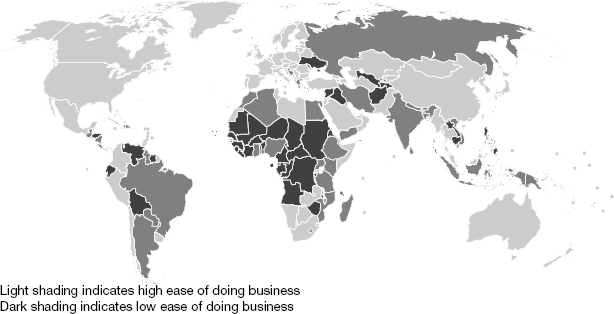

how to succeed despite rampant corruption. In terms of the ease of doing business,

India is a tough place at number 132, but again is highly representative of many other

markets, such as Brazil (number 130) and Indonesia (128), according to the World Bank.

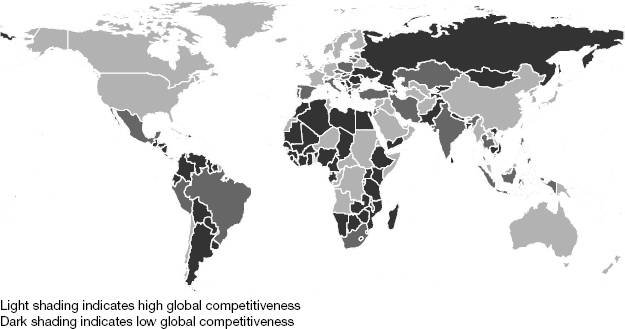

In the World Economic Forum’s

2012 Global Competitiveness Report

, India, at number 59, is just behind Brazil (48) and ahead of Russia (67). Again,

most emerging markets, such as Indonesia (50), raise the same issues and challenges

as India does.

FIGURE 1-2

Global corruption index

Source:

Reproduced with permission of Transparency International.

FIGURE 1-3

World Bank ranking of countries based on ease of doing business

Source:

Wikipedia, see

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ease_of_Doing_Business_Index.svg

.

FIGURE 1-4

2012 Global Competitiveness Report

Source: The Global Competitiveness Network

, World Economic Forum, Switzerland, 2012.

The inescapable conclusion: doing business in most emerging markets is tough. Frankly,

that’s why they are called

emerging

markets. Global companies will have to learn how to succeed in those unfamiliar and

difficult environments if they want to grow. Both in its potential and in its challenges,

therefore, India is an archetype for many emerging markets, especially democratic

ones. Moreover, since India offers a market with huge potential, substantial managerial

capability, a decent talent pool, and important institutions that many smaller markets

lack, it is a good place for multinationals to learn to deal with corruption, volatility,

chaos, poor infrastructure, and the problems they will face in other emerging markets.

Succeeding in India will help multinationals build critical capabilities for tomorrow.

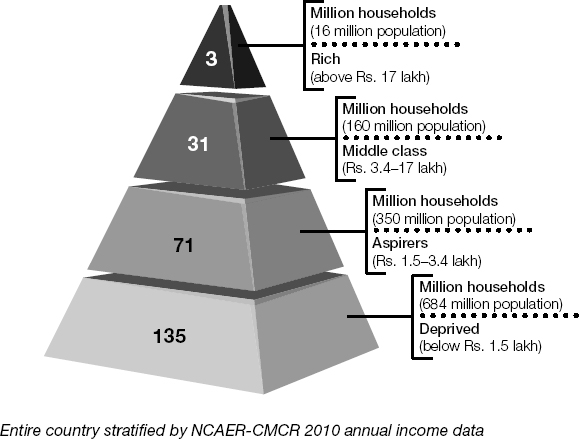

For example, the structure of demand in India is a flattish pyramid with a fat base.

A small affluent segment lies at the top, “the Australia at the top of India,” as

Steve Ballmer of Microsoft calls it. A quickly growing, middle market segment has

the same number of households as Germany and the United Kingdom combined. Tapping

that segment represents a big opportunity. Then, there are the 700 million people

at the bottom of the pyramid who survive on less than $2 a day (see

figure 1-5

).

To succeed, a company has to straddle the pyramid. Smart companies start by selling

global products at global prices to the top but quickly find a way to crack the middle

market. This is not easy, because it requires considerable innovation. Companies have

to develop products in India that are disruptive and offer perhaps 70 percent of the

value of the global product at 30 percent of the price. Think of $100 smartphones,

$2,500 cars, X-ray machines at $400, and so on. To make money at these price points,

companies must localize supply chains and alter business models. They also have to

develop deep distribution that reaches into small-town India and build trusted and

aspirational brands. Once they succeed, they find that the same offerings and capabilities

allow them to win in many other developed and developing countries. Incidentally,

the bottom of the pyramid is not about fortunes, but represents an opportunity to

earn trust and goodwill through corporate social responsibility and shared value initiatives.

FIGURE 1-5

Indian income pyramid

Source:

Aresh Shirali, “The Wealth Report,”

Open Magazine

, March 12, 2011.

Consider a few examples. Take the case of telecom operator Vodafone, which is India’s

largest investor. It has had a tough ride into the market with taxation, regulation,

and brutal competition, but it has learned to make money in the toughest market in

the world, where a phone call costs $0.02 a minute and the average revenue per customer

is $3. This has given Vodafone an advantage in many markets in Africa and Europe.

11

Similarly, for years, tractor manufacturer Deere & Company found it challenging to

compete in emerging markets because its giant tractors and harvesters were too large,

expensive, and complicated for tiny farms. In 2010, Deere finally developed a compact

and affordable thirty-five-horsepower tractor suitable for India. The tractor was

developed in India by a team comprising primarily Indian engineers. It’s now a big

success in India; today Deere exports tractors from its Pune factory to seventy other

countries. By taking on rivals in their home markets, companies like Deere and Vodafone

have also learned to compete with low-cost, nimble, and entrepreneurial Indian and

Chinese challengers.

Hyundai, Suzuki, and Ford have all made India their global hub for small cars. Unilever

is repeating its success with low-cost detergents, sachets, and Pureit water purifiers

in India in many other developing countries. Both Unilever and Novartis have created

new models of distribution to reach less affluent consumers in smaller towns and villages.

These channels account for 10 percent of these companies’ sales, and they are replicating

them in other emerging markets. Unsurprisingly, companies such as Bosch, Dell, Reckitt

Benckiser, L’Oréal, Nestlé, Kraft, Schneider Electric, Honeywell, GE, Cummins, and

Standard Chartered use India as a proving ground for leaders. They send their stars

to India to deliver on tough missions, and Indian stars work overseas, particularly

in Southeast Asia and Africa, which are characterized by high growth and volatility.

A number of leaders are beginning to understand that adversity breeds innovation and

new capabilities; it’s precisely because India is a difficult environment that it

is important to learn to succeed here. They see India as a powerful litmus test of

their ability to succeed in emerging markets. Shane Tedjarati, president of Honeywell’s

New Markets, sums it up: “Our success in China and India has created a model that

allows us to succeed in Brazil, Africa, and elsewhere.” Tim Solso, the former chairman

and CEO of Cummins, stated, while announcing a $500 million investment in 2011 that

includes three new manufacturing plants and a new R&D center in India: “We are looking

at leveraging the capabilities and scale from India to enter Africa.”

12

Commenting on the promotion of India President D. Shivakumar as the head of the Middle

East, Africa, and India regions, Stephen Elop, Nokia’s CEO, said: “India is at the

forefront of the company’s transition strategy. All our dual SIM launches are doing

well, and we are witnessing strong sales. India has shown that brand plus team plus

great execution can deliver strong results.”

13

Clearly, he expects Shivakumar to replicate Nokia India’s success and bring back

market share in the ninety countries in those two regions that resemble India.

India’s strategic importance is not only because it is a large market; more importantly,

it is a laboratory or petri dish for developing products, business models, talent,

capabilities, and operating models that will help companies succeed in a host of challenging

markets. In the global corporation’s architecture, India, along with China, is one

of the key hubs for supporting those markets. You have to learn to win in India to

be able to win everywhere else.

Obstacles are what you see when you are not focused on the goal.

—OLD INDIAN ADAGE

Many multinational companies are quite pleased with their performance in India. That’s

because they have set quite a low bar for success. To most, the fact that their business

in India is meeting budget or growing at double-digit rates is significant.

But that isn’t success. Companies can be growing at double-digit rates and meeting

budgets, and still be irrelevant to their parent and in India. McKinsey & Company

analysis shows that the twenty-five largest, publicly listed multinational companies

in India contributed just 2 percent of their parent’s global revenues and profits

in 2011.

1

That’s telling, especially since many of them have been operating in India for a

long time. The Indian operations of companies that have set up shop since 1991 as

wholly owned subsidiaries contribute an even more anemic 1 percent of their parent’s

revenues and profits. If all these operations grow at roughly the same pace as their

industry, even after a decade their contribution will still be extremely modest.

Real success in India, I would argue, means meeting three criteria:

- The company is a leader in its industry

. That is, it is number one, two, or three in the local market, and gaining market

share. - India delivers 10 percent to 20 percent of the company’s new growth in revenues and

profits on a global basis

. In comparison, China may be delivering 20 percent to –40 percent of global growth. - The company is using India as a hub to win in other markets

. It is taking products developed for India overseas and using the low-cost manufacturing,

engineering capabilities, and managerial talent there to support similar markets.

That may seem like a high bar, but some multinational companies have vaulted over

it. They span many industries such as banking, engineering, food, packaged consumer

goods, trucks, telecom, information technology, and automotive. They are American,

South Korean, Japanese, Swedish, French, German, and British. Some are large; others

midsize. Yet they are all doing well in India by my parameters. In this book, I will

repeatedly refer to this set of winning companies. Despite their diversity, these

companies adopt a similar approach:

- The winning companies straddle the pyramid. They don’t just stay at the top of the

market, but focus on the middle market, developing products tailored for India that

span different price points. Volvo, for instance, offers heavy trucks ranging from

less than $40,000 to $150,000 under different brands, such as Eicher and Volvo. - They create a localized business model, including a supply chain that overcomes local

challenges and delivers margins even at aggressive price points. A case in point:

McDonald’s India, which makes money even at the price point of 25 rupees (Rs.) for

a burger. - The winners take a long-term view, trading short-term profits for growth and leadership.

They make significant investments in product localization and distribution, and in

creating an aspirational brand, ahead of demand and ahead of competitors. For instance,

between 1995 and 2005, McDonald’s India invested nearly $100 million in setting up

a supply chain, creating a brand, and developing a low-cost business model before

ramping up its presence across India. - Smart multinationals run India as a geographic profit center, empowering the local

organization to grow the business. They are also quick to localize the top team, reducing

their dependence on expatriate managers. - Finally, they develop the resilience to deal with India’s corruption, uncertainty,

and volatility, and proactively manage reputations and influence regulations.

Take the case of UK-based construction equipment company JCB. India is the jewel in

the JCB crown, contributing over a third of its revenues and perhaps half its global

profits. The company has a very substantial share (estimated at 55 percent by industry

sources) of the fast-growing Indian construction equipment business, and it is beginning

to use its low-cost manufacturing and engineering capabilities to compete in other

developing countries. Invigorated by the capabilities it has built in India, JCB has

become a global leader in its industry. By contrast, Caterpillar, the world’s biggest

construction equipment maker, has struggled to get its act together despite being

an extremely well-managed company. Caterpillar languishes in fourth position in sales

of construction machines in India. In a 2009 interview in the

Financial Times

, then chairman and CEO Jim Owens said he was “disappointed” with Caterpillar’s weak

showing in India, but was “determined we will do better.”

2

Since then, the gap between JCB and Caterpillar in India has only grown bigger. (See

“

David versus Goliath

.”)

in India

A

nthony Bamford, chairman of UK-based construction equipment manufacturer J C Bamford

Excavators Ltd., stood in the sweltering heat of India to watch swarms of workers

manually moving tons of earth and stone at a construction site outside Delhi. He was

no stranger to the country; this was perhaps his twentieth visit since he first started

coming to India as a student in the 1960s and especially after 1979 when JCB established

a joint venture (JV) with its Indian partner, Escorts. The JV had done reasonably

well, carving out a decent market share in the tiny Indian construction equipment

market (approximately the thirtieth largest in the world in 2003). However, Bamford

could sense things were changing. The industry was finally beginning to grow at a

decent pace, albeit from a tiny base. This had attracted the attention of global leaders,

including Caterpillar, Komatsu, Volvo Construction Equipment, and Case New Holland,

which had all launched competitive products and were nipping at the heels of the JV.

Would JCB be able to ride the construction boom and retain, if not increase, its market

leadership?

On the flight back to his home in Gloucestershire, Bamford mulled over what he had

seen. Although he had been visiting India for years, he sensed a new dynamism and

energy in the air. New construction was beginning everywhere—malls, commercial complexes,

homes. The government finally was moving on the big national highway projects. Now

a new can-do spirit informed all his meetings, whether with dealers, customers, or

even the construction workers he had spoken to. As a result, he sensed that contractors

were willing to invest in new machines and new projects.

But was this for real? Over the years, he had seen similar moments of optimism and

energy, only to watch India lose steam and disappoint. Confronted with big opportunities

in the United States, China, and Brazil and smaller opportunities in other emerging

markets, was it really time to make a big bet on India? He could see that it was not

simply a matter of bringing more machines into India. The market in India was fundamentally

different. Construction projects were smaller, people had less money to invest, and

in most cases, contractors would be buying their first machine ever, having relied

for decades on manual labor. The JV would need a simple, inexpensive, and versatile

machine instead of sophisticated, costly, and very productive excavators—a Swiss-army

knife rather than a more specialized carving knife. Manufacturing would have to be

completely localized to keep the pricing competitive. Bamford could see that the dealer

network would have to be completely overhauled to provide the kind of customer support

and service across India that JCB was famous for globally. He wondered if Escorts,

its Indian partner, shared this vision and had the same appetite for investment and

growth. The transformation would require strong Indian leadership, a new level of

capability on the ground, and much more collaboration between JCB’s UK headquarters

and India. Most of all, it would require greater engagement and more active sponsorship

from him personally. How should he prioritize India over other product and country

investment opportunities?

Being a privately held company, JCB was able to move swiftly after Bamford made up

his mind to focus on India. The results were impressive. By 2011, revenues had grown

nearly fifteen times, and India was now a powerful growth engine for JCB, its largest

market worldwide, accounting for about a third of global revenues and perhaps half

of its profits. Strategically, JCB had built a dominant market share. The name “JCB”

had become synonymous with the industry and virtually the generic term for any construction

machine. As the Indian construction equipment market is taking off (it is expected

to be one of the top five markets in the world by 2015), JCB is extraordinarily well

positioned to ride the wave, while its competitors, including Caterpillar, Komatsu,

and Volvo, are scrambling to find a way to participate more effectively. How did JCB

do it?

- Strong and visible leadership commitment to India

. Anthony Bamford, Alan Blake (then head of manufacturing and now the global CEO),

and the leadership team at JCB invested time on the ground to understand the market

in a nuanced way. They were therefore able to pick up the early signals that drove

them to preemptively invest in India and create the market for their machines at a

time when India was number 30 in the global construction equipment rankings. JCB competitors

underinvested in India. In contrast to JCB, they prioritized India according to the

current size of the market rather than the potential size, delegated responsibility

for India to midlevel managers in their Asian regional headquarters, and invested

in proportion to the size of their existing business rather than the opportunity.

More important, leaders at JCB were personally engaged in helping build the business

in India; they were deeply involved in developing the dealer network, in product development,

in the manufacturing strategy, and in building capability on the ground. Nor did their

commitment wax and wane with the ups and downs of the Indian economy; in the middle

of the financial crisis of 2008, when most competitors froze their investments in

India, not only did JCB carry through with its $100 million manufacturing investment,

it also put in a massive equipment-financing program to aid customers and dealers.

When demand recovered, JCB was able to dramatically consolidate its leadership. - Leveraged global know-how to develop offerings customized for the local market and

spanning price points

. Unlike competitors Caterpillar, Volvo, and Komatsu, JCB decided to focus on inexpensive

and versatile backhoes, rather than more productive excavators, and in 2005 launched

a new model, the 3DX, which went on to become the best-selling construction machine

in India. JCB engineers worked hard to adapt the global model for India. While other

players optimized their machines for maximum speed and productivity, just as they

did in developed markets, JCB optimized machines for fuel efficiency, understanding

that this is the biggest driver of operating economics. Over one hundred innovations,

small and large, went into making a product that was fully adapted to Indian operation

processes and usage conditions. For instance, it brought down the frictional losses

in the hydraulic system, modified filtration to handle dusty conditions and the use

of diesel adulterated with kerosene, used an aluminum rather than copper radiator

to bring down cost, and a heavier bucket. Discovering that many operators are paid

by the hour while others are paid by the job, it created two switchable modes of operation,

economy and power mode, so that operators could choose when to optimize for fuel efficiency

versus productivity. The 3DX was swiftly followed by an explosion of the product range,

with a three-ton wheel-loading shovel, a wheel loader, a crane, excavators, and finally

a five-ton entry-level backhoe loader—the 2DX—meant for lighter applications in rural

India. With twenty-one different machines, JCB offers the broadest product range of

any competitor. - Localized manufacturing and a robust local supply chain to create a localized business

model that delivers good profitability, even at aggressive price points

. JCB was very quick to completely localize its manufacturing in India, including

the engine, transmission, and cab. Competitors that hesitated to make this investment

ended up with an uncompetitive cost structure and huge exposure to currency fluctuations.

Blake and his team made multiple visits to India to get a nuanced understanding of

the manufacturing capabilities in the country. Instead of visiting companies with

similar low-volume manufacturing processes, they focused on visiting the high-volume

plants of Honda, Tata, and LG. They found the capability to be “mindboggling” and

well beyond what they had seen, even in the UK. As a result, in 2006, JCB undertook

“Project 50” to expand capacity from fifteen backhoes per day to fifty per day, without

interrupting production. The success of Project 50 and the market acceptance of the

3DX machine quickly led to Project 100, the creation of the largest backhoe manufacturing

facility in the world, with a capacity of a hundred machines a day, with an investment

of $100 million. Astonishingly, for a project of this size, it was executed within

eight months. The manufacturing innovations were so dramatic that they reduced the

assembly time from 105 minutes to 52 minutes. JCB has now replicated these process

improvements in the UK and Brazilian factories. As the India team earned its credibility,

it attracted further investments. JCB opened a new set of factories outside the city

of Pune to focus on heavy machines like excavators and wheel loaders. - Invested heavily in building an aspirational brand and a proprietary distribution

and service network with deep reach and capability

. Like his father J. C. Bamford, the founder of JCB, Anthony Bamford had a passionate

conviction that the right products were merely half the recipe for success. The other

part was customer service provided by the dealer network, which by his standards was

woeful in both capability and reach in India. JCB India CEO Vipin Sondhi personally

drove a focused effort to transform JCB’s dealer network, with the support of some

of the most experienced service engineers worldwide. JCB established fourteen area

offices across India and four training facilities for dealer personnel in each of

the four regions. He restructured existing dealerships and added 9 more dealerships

and 145 new service points, bringing the total number of dealers to 57 and service

centers to 430. (In comparison, Caterpillar has 2 dealers with 112 service points;

Komatsu, 25 dealers with 54 service points; and Volvo, 12 dealers with 30 service

outlets.) JCB now expected dealers to meet stringent requirements in terms of facilities,

equipment, and investment in service engineers to deliver a world-class customer experience

anywhere in India. This network runs three hundred customer events and road shows

a year versus thirty by the closest competitor. Recognizing that operator training

is a huge issue, JCB invested in a residential school for training operators and then

showed its dealers how this could be a profitable and loyalty-enhancing new business.JCB also arranged financing through more than fifty banks and financing companies,

enabling thousands of first-time entrepreneurs across the country. Today, over 40

percent of JCB’s machines are bought by first-time entrepreneurs. Moreover, unlike

most industrial companies, JCB also invested significantly in marketing beyond the

usual industry events and road shows. Much like a consumer company, it invested to

have a dominant 50 percent share of voice across media channels and signed up Narain

Karthikeyan, a young Formula One racing driver, to be its brand ambassador. Across

India, buying a “JCB” and becoming an entrepreneur are huge aspirations. - Used joint ventures and strategic partnerships to enter the market

. JCB entered India through a joint venture with the Indian company Escorts because

regulations required it. The JV was a powerful advantage because it resulted in a

completely localized business. The disadvantage was that the JV failed to innovate

and improve, and the value of the partnership diminished over time. When strategic

objectives began to diverge and regulations allowed, JCB bought out its partner. What

JCB did right was not to overly integrate the India business after it became a 100

percent subsidiary; it empowered Escorts to run under a new team. - Localized leadership and empowered the local organization to win

. JCB created an entrepreneurial leadership team and empowered it to build the business

in a way that made local sense. India is a geographic profit center in JCB, and the

India CEO Sondhi reports directly to the global CEO Blake with complete responsibility

for the business in India. Accountability for results is ensured through the execution

of a rolling three-year plan around which everyone is aligned. Seventy percent of

the operating decisions are made locally and the balance, consultatively. Strong local

accountability for the business and the traditional JCB value of

jamais contente

(never satisfied)—a sense of urgency about getting things done—has allowed it to

be much more agile than competitors that have failed to create local empowerment. - Leveraged India for global products, services, and talent

. Having built significant capability on the ground, JCB is now using India to win

globally. Exports of components and machines from India are giving it a global cost

advantage. JCB is leveraging a large engineering center and success with frugal engineering

globally. It is using India to develop global leaders and sending high-potential young

Indians to other parts of the world.