Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere (3 page)

Read Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere Online

Authors: Ravi Venkatesan

The reason some companies are extremely successful in India is simply their extraordinary

commitment; this commitment comes from seeing the

potential

of the market rather than its problems. Many years ago, one of my marketing professors

told the class the apocryphal story of two shoe salesmen who are sent to Africa. One

comes back in despair because he found that Africans don’t wear shoes; there simply

wasn’t a market. The other sent a telegram back, “Natives are friendly STOP No one

wears shoes STOP Huge potential STOP Am staying on STOP Send container load of cheap

durable sandals END.” Companies like Samsung or JCB are winning in India because they

are focused on India’s potential rather than its many problems. Determined to build

a leadership position in what they are convinced will be one of the world’s largest

markets, they are willing to prioritize India over other markets. They make market-shaping

investments and sustain their commitment through the tumultuous cycles of the Indian

economy. In the process, they create new markets or categories that they then dominate.

In contrast, their competitors take the same low-risk, low- commitment approach to

India as they do to all emerging markets. The strategy in India, as in all markets,

is selling to the affluent top of the pyramid, which requires the least adaptation

of products, business models, and operating procedures. It is easier to skim the top

of the Indian market than to figure out how to crack the challenging middle market.

They invest cautiously, in proportion to current revenues rather than the potential.

They expect India to operate at the same net profit margin as developed countries,

grow profits faster than revenues, and fund most investments out of the annual budget.

This, of course, results in systematic underinvestment in anything that has a payback

of over a year—building brands or localizing products, for instance. They tightly

control employee head count, even if the cost of an employee in India is one-tenth

that of an employee in France. The country manager is a midlevel sales executive who

reports to the regional sales headquarters, typically Singapore. He or she has to

refer most decisions—hiring five people, investing $5,000, offering a 5 percent discount—to

someone outside India and spends an enormous amount of time negotiating decisions

internally.

For most global small business units (SBUs), India represents about 1 percent of their

global revenues, so double-digit growth and the absence of a crisis are celebrated

as success. Senior executives, including the CEO, make perfunctory annual visits that

are carefully scripted and usually preclude getting a feel for India. According to

John Flannery, president of GE India, this approach “has the risk of resulting in

a low wattage system of low ambition, low commitment, and low energy.” As a result,

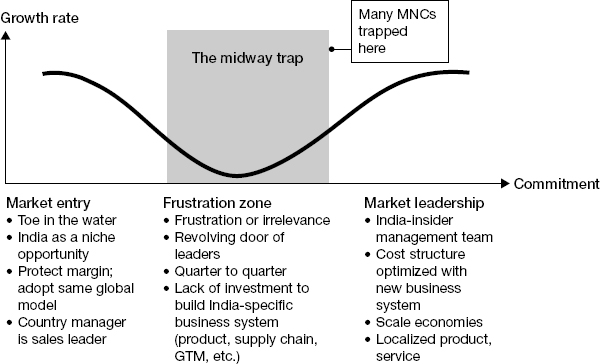

companies end up in the midway trap (see

figure 2-1

).

FIGURE 2-1

The midway trap

Source:

McKinsey & Company Asia Center.

Companies find the going good in the first few years after establishing a presence

in India. Then they find growth slowing down and face a bigger and bigger challenge

to grow faster than the industry average. The small premium segment at the top of

the market gets saturated and intensely competitive as every other global company

targets the same segment. To continue to grow requires the courage and commitment

to move down and compete in the larger middle of the market. However, that requires

market-shaping investments in localization and a different operating model. If a company

doesn’t increase its commitments at this stage, either organically or through acquisitions,

it will sink into the midway trap, where growth is determined by the tide of the industry.

Even well-managed companies like Caterpillar, Volvo, Microsoft, Procter & Gamble,

Nestlé, Dell, and GE have experienced some version of this trap in India.

Microsoft entered India quite early and had built up a reasonable presence by the

time I joined the company early in 2004. During his first visit to India on my watch,

Steve Ballmer had the insight that there are really three segments in India with an

affluent top of the pyramid comprising perhaps 50 million wealthy consumers and 2,500

midsize and large enterprises. This affluent segment is global, using IT devices and

software in ways that are similar to customers in developed markets. Microsoft could

easily serve this market with the same products, pricing, and go-to-market approach,

and the same internal operating model it uses in developed markets. Ballmer felt that

Microsoft should first focus on capturing this opportunity, which he called “Australia

at the top of the pyramid.” Between 2005 and 2009, Microsoft successfully focused

on the enterprise segment. As a result, Microsoft India’s revenues grew at 30 percent

to 50 percent annually and rapidly converged with Microsoft Australia at around US$1

billion. However, once the enterprise segment became saturated, Microsoft found it

more challenging to grow much faster than the software industry did.

To sustain leadership, Microsoft India now needs another growth engine. It has to

figure out how to tap the middle market, which comprises 8 million small and medium-sized

businesses and 50 million middle-class households, which do not use computers. That’s

a profoundly different market, where the value of using IT is not yet understood.

Disposable income is modest, so affordability is a critical issue. The usage of pirated

software is over 85 percent. It’s a mobile market first, a TV market second, and a

PC market third, while Microsoft is still a PC-centric company. In India, customers

are spread across three hundred small cities and towns, not conveniently concentrated

in the top twenty cities. Broadband connectivity is poor, so penetrating this segment

needs a fundamentally different approach—a different value proposition, a different

business model that defeats piracy by delivering software as a service through the

cloud and offers customers the ability to pay as they go, greater distribution reach,

partnerships with telecom operators for connectivity, and so on.

Until Microsoft cracks this proposition, growing much faster than the industry will

be a challenge. It could also be vulnerable to a competitor like Google, which might

exploit this opportunity faster with little to lose. Conversely, if Microsoft is able

to develop a compelling proposition and business model, it could open up large opportunities

worldwide. However, figuring out the approach to the mass market requires a very different

mind-set and approach and a very different level of commitment to the Indian market.

Should Microsoft stay with its standardized model of globalization or double-down

on India to extend its early advantage? Making that decision will be part of CEO Ballmer’s

legacy at Microsoft.

Once a company gets stuck in the midway trap, one of three things usually happens.

A few companies like Cummins, GE, P&G, Volvo, and Nestlé dig themselves out of the

midway trap and relaunch themselves on a high-growth trajectory. For instance, after

a decade of drift, GE India is growing at nearly 50 percent CAGR under India president

John Flannery, with the personal commitment of Chairman Jeff Immelt.

3

Some companies diagnose the slide into the midway trap as a problem with execution

or leadership. The solution, they assume, is to change leaders and simply better execute

the global playbook. A revolving door of expats ensues, but the results get worse.

Reebok India appears to be in this mode.

4

Others, like pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca, conclude that the India market is

simply too hard or not yet mature, so they invest elsewhere, vowing to be back when

the market is more developed, with greater protection for intellectual property (IP),

more favorable policies, or better infrastructure. In both cases, the Indian organization

is starved of the investments and attention needed to grow faster, and the company

will enter a period of drift. Finally, India is consigned to the 1 percent club; the

company’s market share in India will stay in the low single digits, contributing about

1 percent of global revenues and profits.

These companies are implicitly making a decision to cede India to one or more competitors.

Thinking that they will jump back in when the market takes off is an illusion. It’s

hard to time the market, and in several industries, quite a few companies will already

be entrenched. Think how hard it is for Mercedes or Paccar (Kenworth, Peterbilt, and

DAF) to catch up in the Indian commercial vehicles sector, where Tata, Leyland, and

Volvo have a combined market share of 95 percent, or for Renault to catch up in cars,

where Suzuki, Hyundai, Mahindra & Mahindra, and Tata Motors account for 90 percent

of sales. It’s the same story in many industries, including two-wheelers (motorcycles

and scooters), cement, construction equipment, power-generation equipment, and so

on. Digging out of the 1 percent club involves fighting a long and costly battle,

as Volkswagen and Caterpillar are discovering, or making expensive acquisitions, as

pharmaceutical companies have found.

5

The story of GE’s transformation in India shows what it takes to get out of the midway

trap. GE has had a presence in India for over seventeen years, but for the most part,

GE India is no better than an outpost. Theoretically, GE has virtually everything

in its portfolio a growing economy needs, be it consumer appliances, infrastructure,

or financial services. Yet GE failed to capitalize on India’s economic boom, and its

revenues are less than $3 billion; it was therefore a founding member of the 1 percent

club. Longtime GE watcher James Schrager, professor of strategic management at University

of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, remarked: “They have not been successful [in

emerging markets], particularly in India which is such a vibrant place. They have

been late, flat-footed, and missing what the local market needs.”

6

Several factors contributed to GE’s missteps. First, with the exception of its successful

JV with Wipro in health care, the other JVs, such as Godrej GE for consumer appliances,

HDFC GE for consumer finance, and State Bank of India GE for credit cards, didn’t

perform well. In the appliance business, for instance, GE lost India to Samsung and

LG. Indians didn’t want the large refrigerators GE made. In the credit card business,

when GE tied up with the State Bank of India (SBI), India didn’t have a credit bureau.

That meant there was no credit history that companies could rely on to issue cards.

SBI suggested GE tap into the thousands of savings accounts SBI managed to vet a customer’s

track record. “GE just wouldn’t accept the idea. They insisted on getting the information

from a credit bureau and demanded that SBI stand as guarantor for all the cards issued.

You don’t ask for such guarantees in the US, why ask for it in India?” recalls a former

GE veteran, who steered that business for a while. (Note: The JV with SBI did not

perform well historically but with GE’s new approach, it has seen a major turnaround

in the past two years and is growing rapidly and very profitably.)

Executives at GE India found it exasperating to get headquarters’ buy-in for any proposal.

“They just couldn’t understand that in India, the payback time is longer,” says yet

another former GE executive who now heads a European company in India. The other mistake,

old-timers at GE say, was the company’s propensity to send in midlevel executives

from other markets to head the India business. India was far more complex than anything

those executives had handled, so GE needed more rather than less leadership capability

to grow the local market. Schrager points out that the powerful global business units

may also have been a challenge:

Jack Welch made one powerful change in GE, which is to have as small a corporate office

as possible. Division presidents run their global business with as little intervention

from corporate as possible. The great downside of the vertical system is that the

person in charge is very powerful. So if GE, the corporation, wants to go to India,

Immelt or whoever is running the place has to go to each president and lobby for that

business to go to that place. It’s clumsy.

To his credit, CEO Immelt recognized this. In 2009, he drove GE to embrace a radical

new organizational model in India. Explaining the changes in an interview with

Forbes India

, he says:

[Winning in] India is essential. For GE, winning with India requires a new business

model, one in which we are “local” in every sense of the word. That means migrating

P&L responsibility and major business functions [like R&D, manufacturing and marketing]

from a centralized headquarters to an experienced in-country team that is closest

to the action and uniquely in touch with local customers and capabilities. Shifting

power to where the growth is, putting more resources, more people and more products

in the country, and integrating all elements of the GE product and services pipeline

makes good business sense. This new One GE in India approach will speed progress.

With an integrated team, we can develop products and services designed specifically

to meet local needs and, potentially, for export to other markets. Since we’ve changed

the model in India to align with the market more directly, there’s great excitement.

It gives us entirely new opportunities to develop more products at more price points.

This will help open up access to large, underserved markets in India, China, Brazil,

and Africa while also fueling innovation that opens a door into new markets in the

more developed regions of the world. The establishment of a new business model in

India is an important step and I am eage

r

to see it take off.

The changes in GE’s approach to India are profound. For the first time, GE has a senior

vice president heading India. Flannery, who was previously the head of GE Capital

in Asia, is a trusted veteran with an impressive record. The organization structure

has been changed, with all the leaders of businesses and functions reporting to Flannery,

who has responsibility for GE India as a profit center and reports to John Rice, a

vice chairperson. Flannery and his team have substantial decision rights, including

the ability to hire people and invest $250 million over three to five years to build

local capabilities.

GE’s strategy has shifted to developing more local products for the Indian market

and stronger partnerships to gain scale. “We will treat India the same way as we treat

any other business in the company,” says Guillermo Wille, managing director, John

F. Welch Technology Centre (JFWTC), GE’s multidisciplinary R&D facility in Bangalore.

“This is a big difference for us. Previously, countries were never treated like a

business.” The idea is that the India team in different businesses will define what

products they want and the technology team in Bangalore will develop those products.

Adds Flannery:

One GE is a significant evolution. Our theory is that by concentrating more resources

and decision making in India, we will be able to better serve local customer needs

and ultimately achieve faster growth. We also hope that by conceiving and developing

products for the Indian market, we can in turn use those products to penetrate more

mature markets outside of India. We will still have deep connections with our global

organization, but the center of gravity will move towards India.

There are significant challenges in implementing the new “One GE” model. Some have

to do with building organizational capability in India, like product innovation, supply

chain management, and leadership. But the biggest challenges are internal. Says Vijay

Govindarajan, a professor at Tuck and an adviser to Immelt: “There are other challenges

that will require a mind-set shift. In a HQ-driven company like GE, which is used

to working in a certain way, things like reverse innovation and evolving an Indian

way to do business will face resistance. It will require decentralization of powers

and delegation of authority, which may have some opponents at HQ.” The hope is that

with Immelt backing the plan, the changes will go through. “There is a realization

at the top that people working in emerging markets need to have an explore-and-learn

approach. They have to be profitable but not every month. They can spend money, adjust

and fine-tune their business model, and then make money,” points out Govindrajan.

The experiment is in its early stages, but growth is back: GE India is reportedly

growing at over 50 percent annually.