Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere (6 page)

Read Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere Online

Authors: Ravi Venkatesan

People often ask me why these qualities—courage, high ambition, entrepreneurship,

learning agility, and good people skills—are unique to country managers in India.

They are not; these are essential ingredients of leadership everywhere. It’s just

that India is such a demanding place that the leadership challenge is much greater

than most other roles. In addition, along with China, India is often a microcosm of

the entire company. All the divisions, products, and solutions of the company and

all the functions, ranging from R&D to IT, are likely to be present. The India manager’s

role is therefore a good test and an incubator of leadership, entrepreneurship, and

general management ability.

Recognizing this, several global CEOs see India as an incubator for the next generation

of senior leaders, perhaps even the next CEO. Many companies, like Unilever, Ericsson,

Schneider Electric, and Reckitt Benckiser, use India to accelerate the development

of talented executives in their late thirties or early forties, who have the potential

to be on the company’s leadership team. Jean-Pascal Tricoire, CEO of Schneider Electric,

unequivocally says it is highly unlikely that his successor would not have cut his

or her teeth in China or India.

HOW HEADQUARTERS CAN HELP COUNTRY MANAGERS SUCCEED.

It is not enough to hire a great country leader with the right stuff; multinational

companies need to do all they can to help local leaders thrive. First, they must make

the job attractive to the best and brightest. For instance, the Indian subsidiary

should be a geographic profit center, with significant decision rights. The job level

should be a function of the size of the opportunity, not the size of the business.

The incumbent should be able to grow with the business for between five and ten years

without having to leave India to boost his or her career.

Second, the India and China country managers should report to a member of the top

management team who has lived in and built a business in an emerging market, like

Walmart’s Scott Price, Honeywell’s Shane Tedjarati, or Standard Chartered’s Jaspal

Bindra. Leaders who have worked only in developed markets and have little empathy

for emerging markets can be unintentionally dysfunctional. He or she should not be

simply a hard-driving salesperson, but a strategic manager who is capable of reframing

the company’s aspirations for India and aligning the global system behind them. He

or she should also be capable of creating an environment in which leaders can flourish.

Third, multinational companies must assign mentors to country managers. The counsel

of a leader who has the full strategic picture and the ear of the CEO and other senior

leaders is extraordinarily helpful. I was fortunate to have people like Joe Loughrey,

Cummins’s chief operating officer, and Craig Mundie, Microsoft’s chief technology

officer, as mentors. In companies like Nokia, Renault, and Ericsson, the global CEO

makes it a point to engage regularly with the country heads of important countries

like India. These connections are vital for getting a sense of market opportunities

and spotting stresses in the system. They also boost the self-confidence and motivation

of the India manager.

FROM ONE COUNTRY MANAGER TO ANOTHER

. Becoming the country head in India is most exhilarating and rewarding. If you enjoy

new challenges; if you like to be stretched beyond your abilities; if you like to

learn new things; if you like to visit remarkable places and meet interesting people;

if you enjoy building a business; if you yearn to make a difference to people, to

society, and to your company, there are few roles that can provide the same satisfaction

as being the country head of a multinational in an emerging market. There may be a

formal job description, but in reality, the job is whatever you make of it. Sure,

there are boundaries and you can sometimes feel straitjacketed, but over time, if

you approach the job with the right spirit and time frame, there is little that you

cannot do.

Being the country head can also be brutally tough. This is not a job; it is a 24/7

mission, and it takes many years to accomplish something meaningful. It is intense.

There are many incredibly frustrating moments: when you feel misunderstood and unappreciated;

when you feel angry and let down by people; when you ask yourself if it’s worth it.

It’s an extraordinary test of who you are as a person and as a leader.

To make this one of the defining experiences of your life, two things are important

to recognize. One, you need the right perspective. Remember the story of the three

stonecutters? A man runs into three stonecutters and asks them what they are doing.

The first replies that it is obvious that he is cutting stones. The second says that

he is cutting stones to build a wall. The third looks up at the sky and responds that

he is helping to build a cathedral. They are all doing the same work, but the spirit

and perspective they bring to it is different and so is their experience of it. It’s

much the same with being a country manager. You can approach it as a three-year stint

and do a competent job, or you can see it as a unique opportunity to build an institution,

to affect lives and society, to make a difference, and to leave a legacy. I have found

it much more satisfying to bring such a sense of purpose to the role. That helped

sustain me through many challenges and disappointments. It also helped me be more

successful.

The second thing to recognize is that taking a long-term approach implies that this

is a marathon, not a sprint. It’s important to manage yourself and not burn out. Years

ago, I was asked: if you cannot manage yourself, how can you manage an organization

of thousands of people? Good question. Given the intensity of the role, its challenges,

and its relentless nature, you have to learn to be more disciplined and manage yourself

and your life. This means taking care of yourself physically, eating right, and exercising,

despite the grueling hours and travel. You have to cultivate balance, taking the time

for vacations, being with family, sustaining friendships, and developing a hobby.

That means disconnecting and having the discipline to shut off your e-mail and phone.

It’s important to have people who will be honest with you and give you the feedback

you need to hear. It’s vital to have a good mentor whom you can turn to for wisdom.

Being disciplined makes a dramatic difference to productivity and your resilience.

Those elements are important if you want to achieve your full potential.

5

- In India and China, companies have the opportunity to build multibillion-dollar businesses

but have to work in a challenging environment. To do this, the country head must be

an entrepreneurial general manager, not a sales head. - The country manager role in these countries is a smaller version or microcosm of the

global CEO’s role. There are few roles in a company where a leader has a complete

view of the company and all its products, brands, and functions. So these are ideal

roles to develop the next generation of executive leadership. - Implicit trust in the character, judgment, and competence of the country manager is

of paramount importance, given the cultural and geographic distance and the many risks

in India. Trust has four aspects. Integrity and honesty are obvious. A second is good

judgment; many situations that arise every day require an immediate response based

on sound common sense. Trust is knowing that the country manager is aligned with the

global strategy and that he or she isn’t pursuing a different agenda. Finally, trust

is confidence in the country manager’s ability to execute well and be predictable.

That’s why many companies put a trusted veteran in the role rather than someone who

knows the market. They must resolve this compromise; the country manager must be someone

who knows the market and is trusted. - Many traits and competencies are needed for success, but five are extraordinarily

good determinants of successful leaders: entrepreneurship, courage, a higher purpose,

learning agility, and people skills or emotional intelligence. Assessing candidates

for these qualities and developing them in the pipeline of rising leaders is vital.

The trick in globalizing is to strike the delicate balance between being mindlessly

global and helplessly local.

—ASHOK GANGULY, FORMER CHAIRMAN, HINDUSTAN UNILEVER

October 2010. John Flannery, president of GE India, had a big smile on his face as

he left a celebration in Delhi at which CEO Jeff Immelt had congratulated GE’s India

team for winning a $750 million gas turbine deal—India’s largest order for turbines—from

Reliance Power. The main reason GE India had won against tough German and cheaper

Chinese competitors was speed: the company took sixty days from bid to close. Reliance

Power had been amazed; a year earlier, it would have taken GE India anywhere from

nine to twelve months to put together such a complex deal. Each unit would have negotiated

separately with the customer and lawyers would have taken months to wordsmith each

clause.

This time around, the GE India team, operating under the “One GE” model that Immelt

had unveiled a year earlier, had been empowered to close the commercial transaction

from end to end, which included arranging for financing. Determined to prove the operating

model’s power to Reliance and to GE’s headquarters, the GE India team worked 24/7

to win the contract with the full backing of the global GE network that provided technical

expertise and supply chain capability. It marked the vindication of GE’s new strategy

and operating model for India, and signaled a reversal of fortunes for a company whose

revenues had declined from $2.1 billion in 2008 to $1.6 billion in 2009.

Consider an example from another industry. By 2008, telecom giant Nokia dominated

the Indian mobile handset market, with a share of nearly 70 percent. India had become

Nokia’s second-largest market after China. The company had executed a textbook-perfect

strategy, making an early commitment to India, developing a wide range of models at

different price points, investing in manufacturing and distribution reach, and building

a respected brand. Then, a few unknown Indian companies like Micromax, Spice, Zen,

and Karbonn started offering an unusual product. Using low-cost chipsets from a Chinese

company called Mediatek, their innovation was a handset that could take two SIM cards.

Customers liked these phones because they could take advantage of concessional offers

from Indian telecom operators, which were then waging an all-out tariff war. One SIM

card (and telephone number) stayed constant, allowing friends and family to call.

Customers would swap out the second SIM card every month to take advantage of the

best deal for outgoing calls. Despite frantic pleas by Nokia India for such phones,

it wasn’t until June 2011 that Nokia Finland finally responded by developing the dual

SIM phones, C1 and C2. The consequences were catastrophic: by then, Nokia’s market

share had plunged to under 30 percent, while the upstarts captured almost 30 percent

of the market.

1

Why did Nokia in Finland not respond decisively to what its local team so clearly

saw? How did GE change and allow its Indian operation to move quickly? The answer

to both questions lies in what I call the India operating model.

Until now, multinational companies have done well in countries that resemble their

home markets. They don’t do as well in countries like India that are economically

and culturally very different. Except for a few industries like commercial aircraft

and armaments, a one-size-fits-all approach guarantees irrelevance in emerging markets.

However, standardization is critical to success in a multinational company that plans

to operate in many countries. Limiting product proliferation drives economy of scale,

while replicating structures, procedures, and processes reduces complexity, improves

control, and reduces risk.

The trick though is to get the balance between localization and standardization right.

For every company like Apple that is a nonstarter in India due to its extreme standardization,

there are counterexamples like Phillips that failed because they may have allowed

country organizations too much freedom. Although scholars like C. K. Prahalad, Sumantra

Ghoshal, and Chris Bartlett have studied the problem of how to organize global organizations,

they offer few practical solutions. Because it is hard to manage both globalization

and localization, many corporations default to standardization. This causes them to

be uncompetitive in emerging markets including India. Next I will present some lessons

from companies that have struck a better balance between the two tensions than their

competitors have.

A company will operate in a unique way in one country only because the economic, business,

cultural, and geographic distances from its home market are such that it has little

chance of succeeding if it doesn’t. Does that mean it would be willing to do things

differently in Vietnam or Mozambique? Probably not; the size of the prize has to justify

the cost of operating differently there.

To succeed in big markets like Japan, China, and India, companies need to be willing

to find a good balance between standardization and local responsiveness. In my experience,

I have found that means thinking through four issues that make up the India operating

model (see

figure 4-1

).

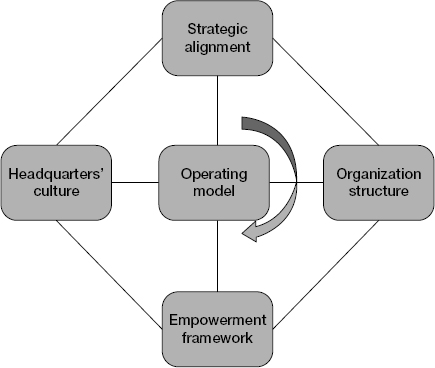

FIGURE 4-1

Components of an agile operating model

- What is the strategy that will help us win in India?

- How do we get the whole company engaged in executing it?

- What is the most appropriate structure to execute this strategy? What is the right

empowerment framework; that is, what decisions are best made locally? What decisions

must be made at headquarters? What decisions should be made jointly and what is a

good process for that? - How does our culture at headquarters need to change to support the strategy?

Let’s tackle each of them.

The first order of business is to get the entire company to develop and execute a

shared strategy for India. The structure and other elements of the operating model

flow from that.

Most multinational companies are matrix organizations; people are responsible for

product divisions or business units, geographies, customer segments, and functions.

Everyone has at least two bosses. Implementing anything requires the consensus and

commitment of a broad group of people, especially the global product divisions that

are often the dominant axis of the organization. Getting functions and product divisions

or business units aligned around a country is often difficult, but it’s powerful when

there is a framework that helps make it happen. That’s when things actually move very

quickly, as we saw in the case of GE turbines.

In the absence of such a framework, every small thing becomes a negotiation and an

act of persuasion, which is time-consuming and draining for everyone. People have

to negotiate every discount and justify every hire. E-mails fly back and forth, frustration

grows, and emotions rise. It’s no one’s fault; everyone is simply doing his or her

job and operating in what he or she perceives to be in the best interests of the company,

except there is no alignment around what will help the company win in India.

Developing an operating framework isn’t easy, but the process must start by creating

a three-year plan for India. I have seldom seen any company achieve a major transformation

without senior leadership committing to a multiyear plan. Ensuring that the company

draws up such a plan and getting the whole organization behind the three or four drivers

of its success are the principal responsibilities of the country manager in India.

With a framework and three-year operating plan that has the blessings of executive

management, the bureaucracy becomes a strength. Everyone executes his or her part,

which is what global companies do well.

That’s how we started at Microsoft India. In August 2004, Kevin Johnson, then worldwide

head of sales and marketing (now CEO of Juniper), corralled Steve Ballmer and a number

of the most senior people at Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond, Washington, into

a conference room with my India leadership team. We seized the opportunity to outline

and discuss how to recalibrate aspirations and invest in seven growth areas in India.

Because of the excitement that resulted in the room, in October 2004, Craig Mundie,

then chief strategy and technology officer, and Johnson led a team of twenty-five

senior Microsoft leaders on a one-week visit to India.

On day one in Delhi, we got the visitors to arrive at a common understanding of India

and Microsoft’s business in India, mainly through presentations and guest speakers.

On days two and three, the visiting executives immersed themselves in various aspects

of doing business in different parts of India. Some visited large Indian business

process outsourcing companies like Infosys and Wipro in Bangalore; some spent time

with small software companies in Hyderabad. Others visited big customers like Tata

and Reliance in Mumbai, while the rest spent time with ministers and bureaucrats in

Delhi to understand the government and policy issues. On day four, we reconvened in

Delhi and shared experiences and observations. By the end of the day, Johnson and

I had led the group to develop what became our first five-year strategy for India.

This investment of senior management time transformed Microsoft’s trajectory in India.

The resulting energy, quality of ideas, and commitment were astonishing. The budgeting

process in December operationalized the plan, and Microsoft India was off to the races.

We accelerated growth from 13 percent a year to over 35 percent per annum (CAGR) over

the next five years. We struck partnerships with big Indian IT firms like Infosys,

transformed our relationship with the government of India, and established new businesses—Microsoft

Research, Microsoft Global Services, and Microsoft IT, for instance—to leverage the

talent in India. In three years, India had become the fastest-growing market in the

Microsoft world, and Microsoft India was consistently rated one of the country’s most

respected companies.

Similar processes worked in other companies; the details vary, but all resulted in

the entire company becoming committed to a multiyear plan for India. Dell’s India

CEO Ganesh Laxminarayan got his extended team together in 2010 and developed an aspirational

plan called “3 In 3;” that is, grow from $1 billion to $3 billion in three years.

He leveraged a visit by Michael Dell to get broad support and feedback, and followed

up by having strategy reviews via videoconference with each leader in Austin, Texas,

to create commitment and interlock. The plan, 3 In 3, has become the operating plan

for Dell’s units in India and is the basis of all discussions with the parent company.

At JCB India, managing director Vipin Sondhi realized that the keys to success were

a manufacturing transformation and an overhaul of the dealer network. In 2006, he

engaged Alan Blake, then the head of manufacturing and now JCB’s CEO, in developing

a plan for transforming JCB India. A team from headquarters visited world-class manufacturing

plants in India, like those of Maruti Suzuki, Tata Motors, and Tata Automation, and

developed a road map for manufacturing JCB products in India. A second team focused

on modernizing and extending the dealer network. Despite the Great Recession of 2008

in the United States and Europe, JCB chairperson Sir Anthony Bamford insisted that

the company follow through on the plans. By 2011, the result was the creation in India

of the world’s largest, most modern, and lowest-cost manufacturing facility for backhoe

loaders and a contemporary dealer network for construction machinery.

A common set of principles guided all three approaches:

- The company must develop the strategy collaboratively between the Indian leadership

team and senior leaders from headquarters drawn from various functions and divisions.

It is therefore not India’s strategy, which is easy to ignore, but rather the company’s

strategy for India. That engenders a different level of commitment at headquarters. - There is a multiyear plan for market leadership that is refreshed every year. Most

multinational companies that operate on a one-year plan end up taking a short-term

view of the business in India. Investments that take more than one year to pay off—in

setting up a manufacturing plant, building distribution reach, or localizing a product—are

deferred. Moving to a three-year horizon is critical to unlock growth, and the company

should revisit the plan as often as necessary. Bosch does that annually; JCB, given

the explosive growth between 2004–2007, every quarter. - The company develops the strategy through immersive experiences in the local market.

In large companies, executives review and debate strategic plans in meeting rooms,

dominated by financial numbers, PowerPoint slides, and Excel spreadsheets. Decision

makers at headquarters usually ask for more and more data. However, since they lack

a visceral feel for the market, the risks seem bigger and the opportunities seem smaller.

The insatiable appetite for more data and evidence leads to costly delays, and eventually,

the company will have to play catch-up with rivals.In contrast, one successful Indian entrepreneur spends a lot of time in retail shops,

simply watching and listening. That, along with gut feelings, gives him the confidence

to act swiftly on business opportunities without endless cycles of debate and data

gathering. Global companies must ensure that their market discovery and strategic

planning process in India, and other key markets, is immersive so that senior leaders

develop an intuitive sense for opportunities, not just a data-driven point of view. - The global CEO must play an active role in the process. He or she has to provide the

mandate for developing a strategy in the first place, must be engaged in reviews with

the executive management team, and must help resolve contentious issues, such as how

additional investments in India will be funded, who has the final say on pricing and

hiring in India, whether the company must develop market-specific products, and under

what brands the new products should be sold. It is imperative that the CEO hold the

executive leadership accountable for the results in India, not just the leader to

whom India reports organizationally.

THE THREE HORIZONS.

Talking about an India strategy across industries and companies is difficult, but

a few themes are evident. One theme is that the greater the dependence on government,

the less attractive the business. All the evidence suggests that industries dependent

on state policy, government regulations, and access to public resources, like infrastructure,

mining, and natural resources, find tough going in India. In fact, given the regulatory

problems and corruption, multinational companies find it nearly impossible to enter

and succeed in these industries. By contrast, sectors at an arm’s length from government,

like banking, IT, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods, flourish even when the state

may be ineffective.

A second theme is that a company needs to straddle the pyramid to be successful in

India. It has to sell global products at global prices to the affluent, innovate to

find success in the middle market, and engage with the bottom of the pyramid through

social enterprises, shared value initiatives, and public-private partnership with

the government. The India opportunity in most industries is not the small global segment

at the top, but the big middle market. This is as true for industrial products as

it is for consumer goods. For instance, in India’s commercial vehicles market, sales

in the premium segment are around one thousand trucks a year, while the market volume

is around three hundred thousand trucks. To make a mark in India, companies can start

at the top, but they must break into the difficult middle market, developing a localized

business model that allows them to be profitable at low price points.

Cracking the middle market takes time. Companies have to experiment, tweaking products,

pricing, and go-to-market approaches to build a low-cost business model. It takes

iteration and debate over what elements of the global model they should modify. Moreover,

India is not one market; it is much more a region like Europe. Companies have to develop

granular strategies covering segments, products, cities, and channels. That takes

time and tenacity. Tata Cummins took six years to achieve a profitable business model

and three more years to pay off all accumulated losses. The joint venture now generates

a healthy chunk of Cummins’s global profits.

Figuring out the approach to the top, middle, and bottom of the pyramid in India conceptually

mirrors McKinsey’s three horizons growth model.

2

Horizon one, the here-and-now priority, entails replicating the global business model

in India, while horizon two involves figuring out a successful model for the middle

market, which will take significant investment and energy. Horizon three contains

ideas for long-term profitable growth; these are usually small experiments, research,

and investments in social enterprises and start-ups. At Hindustan Unilever (HUL),

a horizon-one priority would be to sell more Dove soap or Surf detergent to upper-

middle-class homes. Horizon two might be scaling HUL’s rural distribution system through

women’s self-help groups. The Pureit water filter, a fundamentally new business for

Unilever, is a horizon-three opportunity.

Nitin Paranjpe, head of HUL, articulated a third theme. While HUL is well established

in India, the market is intensely competitive and its leadership is under attack by

lots of hungry competitors. What matters most for HUL is to be at the head of major

market trends and disruptions. “What we need to ensure is that we position ourselves

ahead of trends, so they provide a tailwind and not a headwind,” explains Paranjpe.

Planning at HUL, stemming I suspect from its near-death experience with low-cost detergent

manufacturer Nirma two decades ago, is driven by the identification of the most important

trends. Some recent trends that HUL is concerned with are sustainability, the rise

of organized retail. The strategy process ensures a robust point of view on each trend,

and the country manager must develop a plan to benefit from them. Agility is about

spotting these trends early; it’s not about running after them later on. Having a

dominant market share in the emerging trend is critical. For new entrants, especially

those up against entrenched incumbents, it is critical to embrace new trends ahead

of the incumbent; that’s their only chance of getting into the game.

Another strategic decision is on the use of joint ventures and acquisitions to gain

scale. These are important ways of building critical mass and scale in a new market

like India. Making joint ventures work is challenging, but companies like Cummins,

Volvo, Suzuki, Honda, and GE have been successful in doing so. Acquisitions too have

risks and are often value destructive, but can speed up growth, as Schneider Electric,

DHL, and Abbott Laboratories have done in India. (In

chapter 6

, I will discuss the use of JVs and acquisitions in greater depth.)

Finally, growth in markets like India often occurs in unpredictable spurts, rather

than in a continuous fashion (see

figure 4-2

). Few people anticipated how the economy would lift off in 2004–2005; fewer anticipated

the rapid deceleration in 2011. A company needs to position itself well, and when

the spurt starts, give it everything it has and ride the tiger. This is not the time

to hold back or limit investments or support. Later in this chapter, I will describe

how JCB seized the moment. Another company might have celebrated 40 percent growth

and been satisfied. But what if there is an opportunity to be growing at 100 percent?

It’s important to floor it. Most races are won in the turns; anyone can floor it on

the straights. So it was at JCB, where the whole company exerted itself to push the

limits in India. The results were amazing.