Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere (7 page)

Read Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere Online

Authors: Ravi Venkatesan

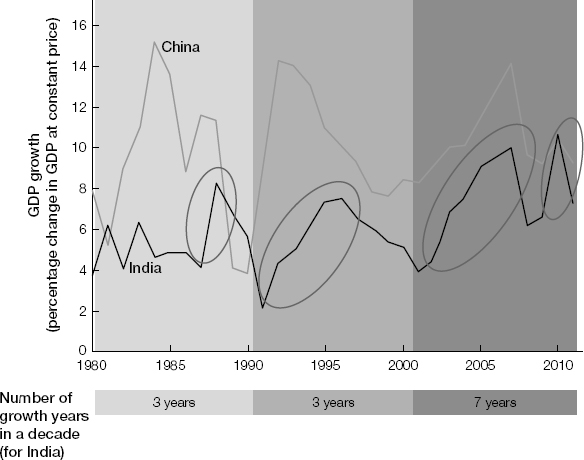

FIGURE 4-2

Growth in India happens in spurts followed by periods of slowdown (compared with China)

Source:

International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2012.

As I conducted my research, I discovered that any discussion about organizational

structures touched a nerve in nearly every company I visited. In most multinationals,

there are global divisions and functional organizations in each region. So the HR,

finance, and legal departments in India report to their global counterparts functionally,

as do the different business units. This is often taken to an extreme, where different

parts of finance—tax, treasury, and accounting, for instance—report separately to

different heads. In HR, training, compensation, and benefits also report globally,

rather than to the India HR head. The strong country organizations of the 1960s, led

by powerful managers who ran their operations with a lot of freedom, have given way

to stronger global product divisions and global functions.

There are several reasons for this approach, but the fact is that in many companies,

the dominant axis is the business unit or product division; those businesses are global

and their presidents are accountable for financial results. They naturally want control

and linkages with their businesses in every country. In theory, these linkages are

important for understanding local opportunities, developing local talent and capability,

and supporting the local business with deep expertise, investments, and resources.

It’s a sensible way to run a global business.

Unsurprisingly, most country managers hate matrixed organizations with dual reporting

relationships. This is not an issue of control or ego; the problem is that since India

contributes only 1 percent of global revenues, it gets 1 percent of the attention

of the senior people at headquarters and even less of the investment. They can meet

global targets without paying much attention to their business in India, which will

stay stuck in the midway trap that I described in

chapter 2

. Dual reporting often leads to confusion, turf battles, unclear accountability, and

enormous amounts of time spent in negotiating simple decisions. There is a high risk

of losing flexibility and speed, especially in geographies where the confusion is

exacerbated by language, time zone, cultural, and hierarchical barriers.

Senior leaders in multinational companies are ambivalent about creating straight-line

in-country reporting and accountability for all businesses, pointing out that there

is no ideal structure. Whichever axis a company organizes around—product, geography,

or segment—it has no choice but to make the other two axes work. In their seminal

book

Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution 2002

, Sumantra Ghoshal and Chris Bartlett argue that matrix organizations are a frame

of mind rather than a structure.

3

Companies need general managers with matrices in their minds.

However, creating the culture that supports matrix management is hard. A fascinating

case study by IIM Bangalore lays out the challenges of Bosch in India as it moved

from a geographical to a matrix organization where global product groups dominate.

4

The new organization created fragmentation, conflict, and other challenges, while

pursuing opportunities and managing across businesses in India. For instance, the

authors write:

Previously, Bosch in India was one group. There was a country head and all issues

pertaining to India were resolved efficiently. With multiple reporting within India

… there are conflicts and, often, long delays in resolving simple issues. Since production

divisions and sales divisions are different, they now fight over transfer prices …

This often leads to a blame game. A lot of time is spent on conflict resolution. The

head of a division in India has to report to the managing director of Bosch India

for disciplinary (i.e., administrative) purposes and to a person in the Asia region

for his targets. Within the division, there are three verticals: Sales, engineering,

and manufacturing. The head of engineering reports to the head of the division for

disciplinary purposes but to a different person in Asia for targets. The same holds

for the head of manufacturing. Each also has a functional reporting relationship with

a third person, who may be located in another geography. Earlier, investment decisions

were made in India. Now that people in Germany drive these divisions, some of these

investments may be unsuitable for the Indian context. For instance, they may want

an investment in an automated assembly line based on the European context even if

in the Indian context, manual assembly may be more suitable.In the past, the country head might see potential in the market that the business

group did not see. The global group will have global priorities and may neglect India

in preference to another geography. An Indian client may develop an engine and want

us to develop a component but we might not be able to take it up, as it may not get

the approval of the global products group. In the past, we developed things like a

hand-held marble cutter, which has a market only in India. We might not be able to

do that now. There is less discretion in maintaining practices unique to the Indian

context. For example, taking high-performing dealers on a trip was possible with local

approval. Since this is not the practice in other countries, it is difficult to get

approval from the global products group, which is a norm in Indian industry. Executives

in India also feel that the culture and low maturity of managers makes the matrix

harder to work in India. Multiple reporting relationships give scope for personalities

to come into play. Strong assertive personalities dominate weak and submissive ones.

5

The dual reporting structure in many companies can be made to work, but it requires

mature leaders, both at headquarters and in the regions, who are able to keep the

best interests of the company ahead of their functional or divisional interests. Imprinting

the matrix in the mind of managers and establishing processes for making dual reporting

work—for instance, joint performance appraisals—take thought and effort, and many

companies haven’t done what it takes. The global leaders of divisions and functions

must have country-specific goals for major countries like India, so they are forced

to engage with it.

Even so, the matrix structure is a compromise. I am skeptical, particularly when companies

want to grow faster than the industry. Companies that lack scale in India need to

bite the bullet as GE has finally done. It is better to move to a simple structure

where all the functions and businesses needed to execute the business plan report

to a country head who becomes the point of accountability. Then the country manager’s

job is to ensure coordination and alignment with global functions, segments, and product

divisions, and to make the matrix tick, while the three-year plan becomes the vehicle

for creating alignment. If the country manager is a senior executive whom headquarters

trusts, this will not pose a big risk.

The logic is simple: India is 1 percent of the business for a global president in

New York; it is 100 percent of the business for the country manager in Delhi. Focus,

proximity to the market, and connecting every day with local people result in commitment,

intensity, and insight, which are hard to get otherwise. That’s a major factor in

the success of Cummins, JCB, Nestlé, Schneider Electric, and, since 2010, GE India.

GE India is a classic instance where putting all the responsibility and accountability

under a strong, senior, and trusted country president with the authority to make most

operating decisions pertaining to commercial terms, hiring, and investments up to

$250 million (over 3–5 years) has transformed the company’s performance. After stagnation

for much of the last decade and decline in revenues in some years, GE India is again

growing at nearly 50 percent annually. Conversely, a radiating organizational structure,

where every leader reports to someone different outside India, is affecting the performance

of companies like Caterpillar and Salesforce.

Sure, there are challenges with making the country the dominant axis. Some local leaders

in India may experience a loss of autonomy; they will have a boss in the same country

far more engaged with their business than a boss in Singapore or Paris. There may

also be loss of prestige. “They were ministers in the federal government of GE, and

now they’re ministers in the state government of Flannery,” points out an observer

about the changes at GE. Global business heads will have concerns, too; someone else

will be making strategic, investment, and operational decisions about their businesses

in India. First China, now India; where will it all end?

Country managers, too, must learn to deal with the stresses of operating in such models.

For instance, when I led Cummins in India, we deviated from the global go-to-market

model in our power-generation business. Cummins designs, assembles, and distributes

or sells generator sets. In India, we decided to strike strategic partnerships with

three generator set manufacturers. They would make and sell the sets but based on

a standardized design, using key components that Cummins supplied and with Cummins’s

dealer network providing after-sales service. This was hugely successful because it

combined scale economies and standardization with the entrepreneurial flair of local

businesspersons. We came to this decision to deviate not unilaterally, but collaboratively

with the global business head and agreed to approach it as an experiment. There were

other times when we made more unilateral decisions about pricing, product features,

or investing in a business that was growing locally but faced an investment and head-count

freeze globally. Those were the right decisions for India, but contentious, and the

CEO had to arbitrate. This tension, when it plays out constructively and collaboratively

between senior leaders, makes the model successful.

To accelerate growth in India dramatically, the country organization must be powerful.

However, once India is a significant part of the global business, it may make sense

to go back to the traditional model. When the organization and its leaders are mature,

people and talent flows are strong, and it becomes important to scale innovations

and capabilities in India to other markets, the pendulum may have to swing toward

more integration rather than geographic focus. That’s what Unilever is trying to do

under current CEO Paul Polman and perhaps why GE in China is still aligned globally.

THE UNDIVIDED INDIA ORGANIZATION.

India and China are unique in that multinational companies have multiple back-end

operations in those countries, including IT, engineering, and global procurement.

Each unit is independent, with a strong leader reporting to a global head. These units

must have tight operational linkages with their functions at headquarters, but it’s

important that the leaders of these units administratively report to the local country

manager.

The country manager must formally be the first among equals and play the role of unifier

across these disparate units, so the public face or image is of one company, recruiting

on college campuses is coordinated, and there are opportunities for employees to move

across these units instead of being confined to their own silo. There must be a shared

services model for HR, finance, and public relations and communications across all

these units. There is often an opportunity to leverage the functional and technical

expertise in these units to help customers. Microsoft was successful at leveraging

expertise at its India Development Center, Microsoft IT, and Global Services Center

to help customers get the most out of their IT investments. That became a powerful

differentiator.

It’s important to formalize a One GE, One Microsoft, or One IBM model and not leave

it to people or chance. The country head should lead the India executive team, and

a charter should describe what the team should attempt to accomplish. The global leader,

the country head, and the country HR leader should do the hiring and performance appraisals.

Surprisingly, few companies have actually made the effort to formalize such a governance

model, resulting in compliance problems, people issues, suboptimal business performance,

a fragmented public image, and an unsatisfactory experience for employees who yearn

to be part of something bigger.

Regional reporting is losing its importance in the next phase of globalization. An

Asian regional headquarters that embraces developed markets like Japan, South Korea,

and Australia; emerging giants China and India; and small markets like Cambodia and

Vietnam makes limited sense. Establishing the regional headquarters in pristine and

orderly Singapore, staffed by expatriate managers, can result in another layer of

bureaucracy that slows things down.

China, India, Brazil, and some other emerging markets are distinct, with many similarities.

Grouping them together makes more sense than the traditional time zone regions of

EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa), LATAM (Latin America), and APAC (Asia Pacific).

It also allows companies to appoint leaders who are knowledgeable about emerging markets

and have built businesses in one of them to take responsibility for all emerging markets.

Honeywell’s Tedjarati oversees all high-growth markets and operates out of China with

a miniscule staff, for instance.

Business leaders like Jaspal Bindra, a board member at Standard Chartered Bank, point

out that:

Having a corps of people who know India and other major emerging markets is a benefit

that is only recently begun to be appreciated. They have the context to say, “I can

appreciate this,” “I understand that,” or “That doesn’t sound right.” It allows us

to have a more confident approach to the market with a balanced approach to risk.

Building such an institutional understanding of key geographies at HQ is critical.

Putting an executive in charge who has only limited experience in and of emerging

markets makes little sense.