Depression: Looking Up from the Stubborn Darkness (12 page)

Read Depression: Looking Up from the Stubborn Darkness Online

Authors: Edward T. Welch

And if the decisions don’t get you, the pressure will. Parents reserve spots at select elementary schools soon after their children are born, hoping to give them any advantage possible in a highly competitive world. They try to provide every extracurricular experience humanly possible so children can find their strengths and, perhaps, be in a position for a college scholarship. Children feel the pressure to have vocational ideas by the time they enter ninth grade. Teenagers now make course decisions in high school that their parents did not have to make in college. And even preteens are exposed to sexual situations and their associated pressures and decisions.

4

Teens feel like they face weekly choices that could affect the entire course of their lives, and what if they make a poor choice? Although life before a sovereign God assures us that God is in control, accomplishing his good plans even through our poor choices, it is easy to lose sight of this reality. When we do, we can feel as if an unwise decision has forever doomed us to a path that is second best.

An understandable response to such a pressured culture is withdrawal, paralysis in the face of decisions, fear of making wrong ones, fatigue, and feeling like you could sleep for days and still be tired. In other words, depression is a fitting response to these cultural pressures. The reason it is important for friends and counselors to be alert to this possible cultural influence is that Scripture can now speak more meaningfully. For example, most depression checklists don’t list “Do you understand the basics of decision making and the will of God?” But if this is part of the problem, friends can offer instruction in how to make wise decisions.

5

They can also remind you that, in view of God’s sovereign control, God will accomplish his purposes in our lives even when we make decisions we later regret.

ULTURE

OF

THE

I

NDIVIDUAL

In 1984, Edward Scheiffelin studied a primitive tribe in New Guinea. Among his findings was an absence of despair, hopelessness, depression, or suicide. Studies among the Amish have found similar results. What is similar in these two cultures is the way individuals are part of a larger community. While Western culture is a pseudo-community in which we occasionally cluster in like-minded groups, these cultures have extended families of different people with different interests who learn how to live and work together.

Think about it: how would the statistics on depression change if people felt they were part of a community? Part of a family? In modern Western culture there is nothing bigger than ourselves. Satisfaction doesn’t come from serving others in our extended circle of relationships. Instead, we think it comes from consuming and gratifying personal needs. If a relationship doesn’t suit our desires, it is expendable; we can move on to another. “How do

I

feel?” is the national obsession.

This exaltation of the individual is a cultural value that is gradually changing. There have been a number of Christian and secular critiques of the “me decades” lifestyle. The problem, however, is twofold. First, the damage has been done. The aloneness, isolation, and powerlessness of a self-driven life have already taken root. Second, in a mobile society that lacks spiritual empowerment to love and reconcile, there isn’t much hope for something better.

If this feature of the world contributes to depression, our response is first to know the enthroned God. When we go into the courtroom of the King of kings, we are in awe of him more than we are aware of ourselves. Our troubles become much smaller in contrast to his beauty and holiness. Then, when we listen to the King, his command to us is simple: love others as you have been loved. Love breaks the hold of individualism; it builds new communities out of the ashes of broken and fragmented relationships.

Finally, we band together in churches. Depressed people avoid people and church commitments, but they can also complain about abject isolation. The answer is to humbly accept your purpose. “Let us not give up meeting together, as some are in the habit of doing, but let us encourage one another—and all the more as you see the Day approaching” (Heb. 10:25). Churches are not perfect. How could they be when we are the church? But the Spirit is with the gathering of his people. Church is where you will know more of God’s grace.

ULTURE

OF

S

ELF

-I

NDULGENCE

A corollary to the culture of the individual is the culture of self-indulgence. Whether you look at past slogans of popular culture, such as “If it feels good, do it,” popular psychology’s “Follow your feelings,” or the advertising that fuels our economy, we are surrounded by the belief that we can find something outside ourselves to fill or satisfy us.

The myth is that “one more” will finally bring satisfaction. The reality, of course, is that it just leaves us with a desire for two more, and then three, because we find that one didn’t satisfy. A law of diminishing returns is always at work when our appetites run amok. For those with stamina, the cycle of craving and indulgence can go on for years, but many people glimpse the vanity of these pursuits before they are ruined by them. These are the people who might be prone to depression. Some of them just intuitively see through the promises of self-indulgence. Others have deprived themselves of nothing or reached the zenith of their careers and found it empty.

When we think about the things that can satisfy our lusts, we tend to think of things that satisfy physical desires, like drugs, food, and sex. But self-indulgence can also feed more psychological appetites. The most common desire has been called the need for self-esteem, the endless quest to feel good about ourselves. Some students of depression suggest that the increase in depression is due in part to the backlash of the self-esteem teaching.

The reasoning is straightforward. What happens when people are raised on a steady diet of “You are great, you can do anything, you deserve it, you are the best, you can get what you want”? Sooner or later they find that they are

not

great, they

can’t

do everything, they are

not

the best, and they

can’t

control it all. Depression and denial are the only two options left.

ULTURE

W

HERE

H

APPINESS

I

S

THE

G

REATEST

G

OOD

Ask those living in Western culture what they desire and you will begin to hear “happiness.” Look through the senior pictures in a high school yearbook and the frequent ambition is “I want to be happy.” Even Aristotle’s

Ethics

suggests that happiness is the greatest good. Given such a goal, it is not surprising that we have an ambivalent relationship with hardship.

People who have experienced war have learned to accept the trials and sufferings of life. Among many wise, older citizens in American society, there is no desperate flight from suffering. Instead, there is a recognition that it is a part of life that can have some benefit. Yet among those in the post-World War II generation, a wisp of happiness is the goal, and suffering must be avoided at all costs. If there are hardships in a relationship, end it. If there is an unpleasant emotion, medicate it. It is a generation that perceives no value to any hardship. Like a pampered child who never experienced the regular storms of life, we lack the skill of growing through our trials.

I’m not suggesting that we should pursue hardships. When the pain can be lightened, it is usually a good thing to do. But the point is that we live in a culture that idolizes happiness, and if we idolize happiness, it will always elude us.

ULTURE

OF

E

NTERTAINMENT

AND

B

OREDOM

Another feature of modern culture that has been linked with depression is our quest for the new and exciting, which, for many, is a frantic flight from boredom. “Amuse me” is the theme. If we are not amused, we have the dreadful quiet to fill. As Pascal astutely noted, “I have often said that the sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.”

6

Boredom is a malaise that hangs over the younger generations. Perhaps it is because they have compressed sex, drugs, and money into a shorter period of time and found them unsatisfying. With nothing new to entertain them, they are dreading the decades to come. With no particular purpose, their goal is to tolerate and survive a boring, goal-less existence that will probably be less affluent than that of their parents.

The antidote for boredom is joy. It comes when our hopes are fixed on something eternally wonderful and beautiful. Augustine rightly identified the ultimate object of joy as God.

True happiness is to rejoice in the truth, for to rejoice in the truth is to rejoice in you, O God, who are the truth ... Those who think that there is another kind of happiness look for joy elsewhere, but theirs is not true joy.

7

According to Augustine, true joy is the delight in the supreme beauty, goodness, and truth that are the attributes of God, of which traces may be found in the good and beautiful things of this world.

C. S. Lewis gave considerable thought to the experience of joy. He found it in small, good things such as apples, fresh air, seasons, and music. He spoke of “reading” the hand of God in our little pleasures. Like Augustine, Lewis also wanted to make it clear that joy could not rest in those things, however good.

The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust in them; it was not in

them, it only came through them, and what came through was a longing ... For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

8

This longing is joy. It is a longing for glory, heaven, and, especially, God himself.

Augustine and Lewis echo Paul’s exhortation to the church at Philippi to meditate on those things that are true, noble, pure, and lovely (Phil. 4:8). This exhortation resides in a letter uniquely committed to teaching the church how to have joy in the midst of suffering.

Joy is the natural response when we behold God. What does it have to do with boredom? Joyful people are mobilized. They delight in doing small obediences. They are pleased to serve God in any ordinary way he sees fit. They also know that an army of people taking small steps of obedience is what moves the kingdom of God forward in power.

ESPONSE

When we first listen to depression, we find that the misery is consuming. It doesn’t point anywhere or say anything. It just is. But when we keep listening, it tells stories of loss, rejection, or other events that happened to the person. It speaks of identifiable physiological problems. It points to a culture of irony: the culture with the most peace, money, and leisure is also the one with the most malignant sadness.

As you consider the comments about joy, don’t be discouraged if joy is elusive. It takes time and practice. If, however, you don’t want joy, if you are resistant to considering joy in God, then you are probably angry and avoiding God. The following chapters will give you opportunity to consider this more closely.

What feature of our culture have you absorbed that shapes your depression?

13

The Heart of Depression

Jane was on the verge of hospitalization again. Could she make it another day? Should she be committed? And what do you do when you know hospitalization isn’t going to help? At best, it would temporarily keep her out of harm’s way, which is what it did the other two times.

With her resources alerted and ready to help, her small group leader called and asked Jane the obvious. When someone is desperate, ask about her relationship with God. This wasn’t a new question to Jane. When she wasn’t depressed she found the question to be among the most important that anyone could ask. But not this time.

“Why are you asking me about God at a time like this?”

“Jane, how could I

not

ask you? You are desperate. Where else can you really turn?”

The small group leader was faced with at least two possibilities. One, he had not really listened to Jane and put a spiritual band-aid on a potentially lethal wound. Two, he got to the heart of the mat-ter—there was nothing deeper than her relationship with God—and Jane would have none of it. That doesn’t mean that Jane’s relationship with God was the cause of her depression, but, at least, her depression exposed how, when life was sufficiently difficult and her faith was severely tested, Jane found God irrelevant, which made her relationship with God

very

relevant.

Only later was Jane able to realize that the question revealed her heart: she trusted God when circumstances went her way but not when she went through hard trials, such as depression.

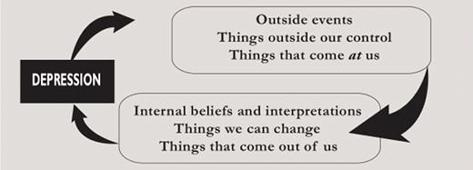

We are trying to carefully dissect depression. We are listening to it, hoping for clues about how it began and how it can be relieved. This led us first to highlight a number of causes that come

at

us. Satan, other people, death, and culture often play a part. The next step is to complete the loop and consider those things that come

out

of us. How do they contribute to depression (fig. 13.1)?