Depression: Looking Up from the Stubborn Darkness (16 page)

Read Depression: Looking Up from the Stubborn Darkness Online

Authors: Edward T. Welch

“Do not be afraid or terrified because of them, for the L

ORD

your God goes with you; he will never leave you nor forsake you.” (Deut. 31:6)

“Do not fear, for I am with you; do not be dismayed, for I am your God.” (Isa. 41:10)

But Zion said, “The L

ORD

has forsaken me, the Lord has forgotten me.” “Can a mother forget the baby at her breast and have no compassion on the child she has borne? Though she may forget, I will not forget you! See, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands; your walls are ever before me.” (Isa. 49:14–16)

“I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Counselor, to be with you forever—the Spirit of truth. ... he lives with you and will be in you. I will not leave you as orphans.” (John 14:16–18)

Imagine the presence of one who deeply loves you and is powerful enough to deal with the things you fear. It turns fear into confidence. But, like all spiritual growth, this change only comes with practice. It comes when you say, “Amen—I believe” when you hear or read the promises of God. It comes through meditation on God’s words. It comes when the cross of Jesus Christ assures you that God is faithful.

These words to the fearful are so important that Jesus makes them his final words on earth: “And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age” (Matt. 28:20). The resurrection is God’s answer to fear. Jesus is alive.

ESPONSE

Fears are loud and demanding. Even when you know they are irrational, they can still control you. It is hard to argue with feelings that are so intense, and easy to be loyal to our inaccurate interpretations. So don’t expect to be writing any psalms of victory just yet. Instead, claim as your own some of the psalms that are journals of

fear. For example, Psalm 46 talks about treacherous circumstances, but it still keeps circling around to the same refrain: “The L

ORD

Almighty is with us; the God of Jacob is our fortress” (Ps. 46:7, 11). Psalm 56 describes being slandered and attacked, but the psalmist calms his heart: “When I am afraid, I will trust in you” (Ps. 56:3). As you meditate on some of the psalms that speak about fear, you will find that you, too, will be able to make quicker transitions from fear to faith (see Ps. 57:4–5).

There are two basic steps in dealing with fears. First, confess them as unbelief. Isn’t it true that much of our fear is our hearts saying, “Lord, I don’t believe you,” or “Lord, my desires want something other than what you promised”? Second, examine Scripture and be confident in the love and faithfulness of Jesus. Ask someone who is confident in Jesus to give reasons for his or her confidence.

What are your fears? Where is your trust?

16

Anger

Fear is the most obvious co-conspirator with depression; anger is the most common. The formula is a simple one:

Sadness + Anger = Depression

Most people can find their anger easily, but sometimes you have to look in unanticipated places.

“Why can’t you believe that you are forgiven?”

This thirty-five-year-old woman had been depressed for ten years and made two suicide attempts. Like many depressed people, everything about her said self-loathing. On this occasion she was describing the guilt she felt for having said something hurtful to her sister. You could actually see her weighed down by it.

Her answer was shocking.

“If I believe that God forgives me, then I will have to forgive my father, and I could never do that.” Her anger was obvious, surprising even herself.

Yes, she was guilty, but her guilt went deeper than she thought. She was guilty for standing in judgment over her father, whose sins in this case were minimal. She did not believe that God was going to be harsh enough on him, so she appointed herself as the judge, jury, and executioner. The fact that this meant that she would have to deny grace and mercy for herself was a small price to pay for the satisfaction of judging him.

Anger will not always be the cause of your depression, although some researchers want to tell you that it is a

likely

cause. But anger is frequently revealed by depression. The wisest way to approach this subject is to assume that you are angry. Anger is as basic to our condition as bipedal locomotion and opposable thumbs. If you are a person with a mind and emotions, you will find anger.

To make this search even more important, remember that anger

hides.

The angry person is always the last person to know that he or she is angry. We will acknowledge that we are depressed, fearful, or in pain, but we are blind to our anger. Anger is always another person’s problem, not our own.

INDING

A

NGER

Anger includes a broad spectrum of behaviors. It can contribute to depression even when you don’t remember a particular cause. Like the Hatfields and the McCoys, neither party remembers what originally started the feud, but they know they are supposed to be angry at one another.

A few questions can help uncover the root.

What are my personal needs? “Needs” are usually a euphemism for “rights” and “demands.”

Where have my needs been unmet?

Where have my rights been violated?

What do I think I deserve that I haven’t received?

Of whom am I jealous?

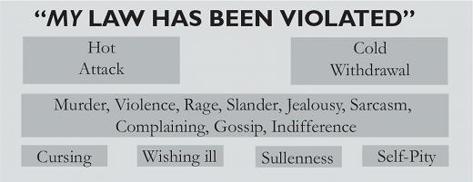

If you limit your awareness of anger to overt rage, you will miss it. Violent anger is just one expression of anger (fig. 16.1).

Figure 16.1. The Spectrum of Anger.

A depressed man said nothing to his wife for one year—not one word. In public he related normally. He elicited sympathy because he didn’t have a job. His rationale for his “quietness” was that he was depressed. But sadness can cover rage.

Anger can be either hot or cold. People are as hurt by one as they are by the other. The main difference is that hot anger is brief and explosive; cold settles in long-term. Depressive anger is usually cold: the “cold shoulder,” withdrawal, calculated rejection, putting blame on others, feeling sorry for oneself. In some ways, it is the most extreme anger in that it refuses to be affected by the other person. “I have been hurt, and I will never care enough to be hurt again.” Avoid the hot-tempered person, but tremble before the cold, distant, uncaring, angry person.

HE

H

EART

OF

A

NGER

Anger says, “You have done wrong.” It is making some kind of judgment, and the judgment is often accurate. Anger might be responding to a real wrong. But this is only the beginning of the story. Once anger settles in, it will bring you to an increasingly familiar crossroad.

Will you turn to the true God, who shows compassion to those who have been victimized, or will you trust yourself?

Will you turn to the true God, who is the holy and righteous judge, or will you form a vigilante party that meets in your name, for your sake, and for your glory?

Anger typically begins in a way that imitates God—it makes judgments about right and wrong. But it can quickly turn into a stance against him. You are angry because your rights and your glory—not God’s—have been violated.

This is where you must be an expert in knowing your own heart. Otherwise you are left groping in the dark. What you can see about anger is that someone did wrong and you are angry. What you

don’t

see is that the anger reveals more about your own heart than it does about the other person. To be more specific, anger is between you and God.

Take grumbling as an example. Who hasn’t grumbled and complained in the last couple of days? Grumbling or complaining fits within the larger category of anger because it is a judgment. The grumbler has declared something to be wrong, be it a person, the weather, or the expensive car repair. Usually, it is directed at no one in particular. It is just a complaint. While those who are overtly angry might shake their fist at God, God rarely is mentioned during low-level grumbling or complaining.

But grumbling is more about us than it is about other people or our circumstances. It is our hearts saying something against God. When Israel was hungry during its journey through the desert, “the whole community grumbled against Moses and Aaron” (Ex. 16:2). That, however, is only the one-dimensional picture. It sees the horizontal but not the vertical. The people needed Moses’ spiritual insights to see more. Moses replied, “You are not grumbling against us, but against the L

ORD

” (Ex. 16:8).

Soon after this, they complained against Moses about not having water. Moses once again diagnosed the problem immediately. Water was not the issue. The problem was their hearts. “ ‘Why do you put the L

ORD

to the test?” ’ (Ex. 17:2).

Moses was making a serious indictment. He knew that God tested the hearts of his people to see if they would follow him during more threatening conditions. That was God’s prerogative, and it taught his people to trust him. But for the people to test God! Moses charged them with standing over God in judgment.

Do you see the role reversal in anger? God has a right to test our hearts. Who are we to test God and question him? It is the height of arrogance. Indeed, our circumstances can be very difficult, but God is God. He has the right to do anything he wants.

This seminal story challenges us to be on guard. During difficult times, we can still blindly follow the mob and test God without even knowing it.

“OK, God, are you present or not? Show me. Show me by ________. And if you don’t show me here and now, I will not trust you.”

Of course, we don’t say this openly, but if we really listen to our grumbling, we will detect words against God.

NOWING

G

OD

When you dig deep, anger is about spiritual allegiances. Who will you trust? Our anger indicates that we really don’t trust God. Therefore, when we identify anger in our lives, we can’t simply say, “I am going to stop being angry.” Such a resolution is admirable, but it is a shortcut that is doomed to fail. Anger is ultimately about God. It shows that we don’t trust him, and it becomes an opportunity to know him better. What you come to understand will surprise you.

God is who you imitate.

God tells us, “Be holy, because I am holy” (Lev. 11:44). If you really want to know what it means to be truly human, learn to imitate God.

God, as you know, is no namby-pamby. He hates dishonest scales (Prov. 20:10), evil (8:13), haughty eyes, a lying tongue, murderers, schemers, false witnesses, those who stir up dissension (6:16–19). He hates the injustices that can be found in divorce

(Mal. 2:16). He hates hypocrisy, especially among the leaders of the people (Mark 3:5). He was indignant when the disciples rebuked the little children (Mark 10:14). There is indeed a time for hatred and anger (Eccles. 3:8).

But don’t get the wrong impression. God’s anger is an expression of his love. If you don’t get angry, you don’t love. If you witness injustice and are unmoved, you do not love the victim. So if God hates dishonesty, he loves honesty. If he hates haughty eyes, he loves humility; a lying tongue, truthfulness; murderers, those who build others up; schemers and false witnesses, peacemaking.

Why does God love these things? Everything God loves is a reflection of his own character.

He

is honest, humble, truthful, and peacemaking. When we love what he loves, it is a sign that we are becoming more like him, as God intended us to be.

When we think of anger, we usually picture someone losing his temper. That can never be the picture of God’s anger. God never loses his temper. Instead, when he reveals his anger, he leaves it on simmer (Ex. 32:9–10, 14). He invites his people to return and reason with him (Isa. 1:18), and he can quickly be persuaded to turn from his anger. For now, God has chosen to place his anger within limits. “ ‘In a surge of anger I hid my face from you for a moment; but with everlasting kindness I will have compassion on you,’ says the L

ORD

, your Redeemer” (Isa. 54:8).

This sounds wonderful when it is applied to us, but it sounds like God could be a pushover as a judge when it comes to our enemies. We like mercy for ourselves and justice for others. To be merciful and just is a tricky combination. If you think about it without divine guidance, you will begin to think that mercy is unjust and justice is unmerciful.

The cross ultimately solves this dilemma. The reason God extends such mercy and patience is because his anger with our rebellion is ultimately poured out on Jesus. Make no mistake: the cross is about love

and

anger. God is angrier than any of his creatures, and the cross

is where his anger and wrath were fully concentrated. When we turn to Jesus, God’s anger is turned away from us and turned toward the cross. His justice is fully satisfied by the very costly price of his Son’s death. Meanwhile, his mercy and love are fully expressed to us as he gives us true life through Jesus’ death and resurrection.