Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (81 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

The titled nobility remained prosperous, commanding, despite its small size, a very high proportion of the nation’s wealth. As we have seen, peers and their greater gentry cousins owned nearly one-fifth of the land in England, and that proportion was rising. The income of the average English peer was perhaps £5,000–6,000 a year, with the greatest magnates (the dukes of Bedford, Beaufort, Marlborough, Newcastle, and Ormond) having perhaps £20,000–40,000 by 1714. The annual incomes of Scottish and Irish peers were much smaller, averaging around £500 – a great, if not quite princely, sum. Nearly all peers relied for their wealth primarily on their landed estates, namely, the profits of agriculture and the yield from rents. As indicated above, these profits were often compromised after 1693 by the Land Tax and the depleted labor market, which kept rents and demand for food low. Nevertheless, the big estates not only weathered these difficulties, they profited from them by absorbing the holdings of those who could not do so. Moreover, as we have seen, since the middle of the seventeenth century if not before, enterprising peers had diversified. Some did well from officeholding: a great court or government place could yield anywhere from £1,000 to £5,000 a year in salary, perquisites (like the right to sell subordinate offices), or pensions. Noble families also invested in London real estate and development, the new joint-stock companies, trading ventures, canals, mines, turnpikes, and the whole panoply of government financial instruments: bonds, lotteries, and the Bank of England. Finally, all great landowning families sought to conserve their holdings by passing them on to a single heir, almost invariably the eldest son, who was usually forbidden, through a legal device called the strict settlement, or entail, from alienating any of the family property. At the same time, holdings might be extended through an advantageous marriage – sometimes with another aristocrat, sometimes into mercantile or professional wealth – or the acquisition of such land as did come onto the market. As a result of these initiatives, most noble families in England, at least, were more than able to compensate for the disappointing performance of their agricultural holdings.

While elder sons consolidated their estates behind deer parks and high walls, the cold realities of primogeniture forced younger sons into apprenticeships costing their parents hundreds of pounds, the professions, and marriage into the middling orders. During the reign of Charles II, an Italian visitor was shocked, thinking that English nobles and gentry apprenticed their sons to “masters of the lowest trades, such as tailors, shoemakers, innkeepers.”

12

In fact, while the nobility seemed to close ranks against their inferiors in general, individual families did maintain numerous connections across class lines.

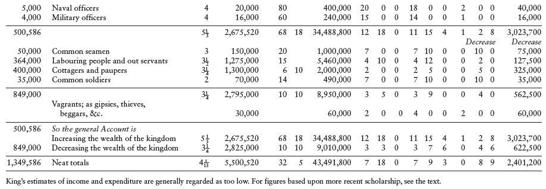

Even more than in previous centuries, their affluence enabled members of the peerage to live lives of ostentation, leisure, and grace, as well as political consequence. In fact, the century after 1660 saw the zenith of aristocratic wealth and power in England. The most prominent noble families displayed that wealth and power by erecting great baroque palaces. The years 1690–1710 saw the building or rebuilding of, among others, Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire (in this one case out of public funds) for the duke of Marlborough, Chatsworth House in Derbyshire for the duke of Devonshire, Petworth House in Sussex for the duke of Somerset, and Castle Howard in Yorkshire for the duke of Norfolk (see

plate 26

). These palaces were often designed or renovated by the greatest architects of the day, such as Sir John Vanbrugh (1664–1726), Nicholas Hawksmoor (1662?–1736), William Talman (1650–1719), or William Kent (ca. 1686–1748). They were decorated by its greatest artists, such as history painter Louis Laguerre (1663–1721), carver Grinling Gibbons, and ironworker Jean Tijou (fl. 1689–1711). They were filled with expensive furnishings, paintings, porcelain, and books, and surrounded by elaborate formal gardens designed by men like Henry Wise (1653–1738), Charles Bridgman (d. 1738), and Kent to demonstrate that even the forces of nature obeyed the commands of their noble proprietors. For an ambitious peer, such a house embodied his wealth and taste and formed the political and social headquarters for networks of friends and followers which extended throughout the county and beyond.

And yet, because their masters played so important a role at court and in London, these houses were only occupied by them for about half the year. From early autumn to late spring, with the possible exception of the Christmas holidays, their owners lived in London. By 1714 the landed nobility was increasingly “amphibious” between the country and the capital and at home in both. As in previous periods, the males attended the House of Lords when Parliament was in session, and some held high office. They and their families enjoyed the pleasures of the season, attending the court, the theater, the opera (newly imported from Italy about 1705), and concerts. Aristocratic men could relax at taverns, coffeehouses, and, increasingly, private clubs (see below). In order to take convenient advantage of these delights and responsibilities, British nobles sometimes built splendid London townhouses, smaller versions of their country houses, also designed and decorated by famous artists. But increasingly, they tended to settle in one of London’s growing number of smart squares often named for the families that developed them: Russell, Grosvenor, etc. By the close of the seventeenth century, some members of the ruling elite pursued a second season at the end of the summer at one of the great spas such as Tunbridge Wells in Kent, Epsom in Surrey, and, most importantly, Bath in Somerset. In fact, these long absences from their country seats may have weakened direct noble control of the localities and contributed to the perception of elite withdrawal. As our period closes, that control was increasingly devolving onto the shoulders of the gentry.

Plate 26

Castle Howard, engraving. The British Library.

Closely allied with the nobility – so that historians often consider them part of the same class – were the gentry (baronets, knights, esquires, and plain gentlemen). By the beginning of the eighteenth century the definition of gentility was even vaguer than it had been under the Tudors. The border separating a gentleman from a prosperous (or prosperous-looking) commoner was blurry and permeable, leading to a much more open society than in the rest of Europe. By the same token, it became increasingly difficult, at court, at a London masked ball, or while taking the waters at Bath, to tell who was gentle and who was not. The lead character in Defoe’s novel

Moll Flanders

(1722) discovered this difficulty when she sought to marry “this amphibious creature, this land–water thing called a gentleman-tradesman,” without realizing that her intended beau might look the part of a gentleman, but his status was all a mirage based on credit. Gentlemen no longer felt it necessary to take out coats of arms or even purchase landed estates. The end of the Stuart period saw the first “urban gentry” or “pseudo-gentry” – often wealthy merchants or professionals – who preferred town amenities to country pleasures.

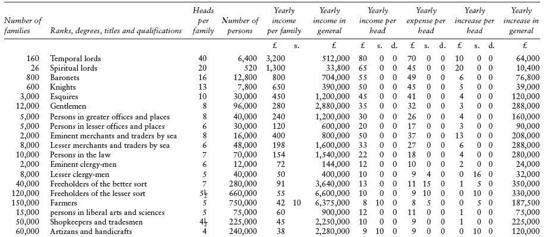

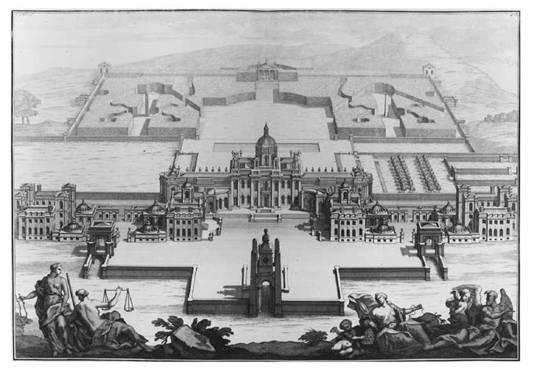

The demographer Gregory King (1648–1712) thought that there were about 16,500 gentry families in England in 1688 (see table 1),

13

but modern estimates range as high as 25,000. There was a smaller number of Scottish and Irish gentlemen. Altogether, the English gentry owned over half of the country. Only the most prominent sat in the House of Commons: the British Commons after the 1707 Union had 558 members, but not all of these were landed gentlemen. By this time, the average gentleman made perhaps £500 a year, but that “average” disguises wide variations in wealth, power, and status. Historians often distinguish between the “greater gentry” and the “lesser gentry.” The greater gentry had incomes averaging over £1,000 a year, and might receive as much as £10,000–15,000. As a result, they lived like all but the greatest peers. Like their noble cousins, they often possessed multiple estates; built great country houses; held a parliamentary seat or influence on one; took office, if not at the center then locally as a deputy lieutenant, sheriff, or JP; and split their time between their estates and the London season, Bath Spa, or (horse-)race meetings at Newmarket or Epsom. Walpole, with his premiership, his great estate at Houghton in Norfolk, and the splendid art collection which it held (today the core of the famous Hermitage Collection in Russia), is the most glittering example of the type.

In sharp contrast stood the lesser gentry, whose incomes might be as low as £200. Often, they held one poor estate with a few tenants. Their local influence was very limited: they rarely held offices above that of JP or sat in Parliament, for they could not afford the cost of mounting a campaign, especially after the passage of the Septennial Act in 1716. While the lesser gentry might be consulted by the real aristocratic leaders of their counties, they would not have a determining influence. Their houses were comfortable, not spectacular; and they rarely left them to go to London. They might, however, take advantage of the growing amenities of the local county town, which, in the eighteenth century, was increasingly likely to build assembly rooms where dances, concerts, and even occasional theatrical productions might be held. Political outsiders, they tended to sympathize with the Tories.

In 1714 as in 1485, the landed aristocracy ran the country, determined its relations with other countries, and set the tone of its culture. For most of the period covered by this book, they did so at the royal court. Until at least the 1680s, the court at Whitehall and elsewhere was the epicenter not only of politics but of government finance, and religious, social, and cultural life. It was, moreover, the great emporium for acquiring places of all kinds, not only in the household but in the Church, the judiciary, the foreign service, the revenue services (Customs, Excise, Land Tax, etc.), the armed forces, and local government. The Restoration court also provided impressive architecture, splendid parks, sumptuous decor and furnishings, dramatic ceremonies, balls, concerts, plays, the royal art collection, free meals, an endless source of gossip, and the greatest marriage market in England. In the Chapel Royal could be heard “excellent Preaching … by the most eminent Bish[ops] & Divines of the Nation,”

14

as well as magnificent choral anthems and organ voluntaries by its greatest composers, Matthew Locke (ca. 1622–77), John Blow, and, above all, Henry Purcell. Their music was baroque: contrapuntally complex and heavily ornamented, it was thought to complement the awesome power of absolutist monarchs. The baroque style had its architectural counterpart in the imposing designs of Hugh May (1621–84) and Sir Christopher Wren at Whitehall, Windsor, and Winchester; the elaborate carving of Grinling Gibbons; and the ornate allegorical ceiling painting of Antonio Verrio (ca. 1639–1707). The denizens of this court were painted in the baroque style by Lely and Kneller; their conversation celebrated in the new comedy of manners being written by “court wits” such as Etherege or Wycherley; their politics and their sexual escapades satirized by poets like Rochester or Marvell. Rarely has so much talent been brought together in one place.

Table 1

Gregory King’s Scheme of the income and expense of the several families of England, calculated for the year 1688