Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (49 page)

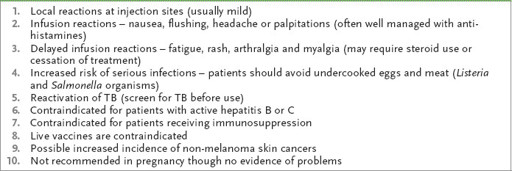

Table 9.5

Side-effects and precautions for use of biological agents

There are two main types of biological agents: the TNF (tumour necrosis factor) inhibitors and the non-TNF inhibitors.

THE TNF INHIBITORS

These drugs block the activation of TNFα, which is an inflammatory cytokine found in the synovium of RA patients. Suppression of synovitis with these agents can almost completely prevent joint and bone destruction. All the TNF inhibitors have to be given by intravenous infusion or subcutaneous injection. The five drugs currently available (

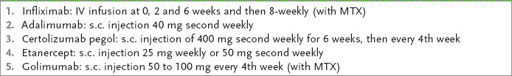

Table 9.6

)

are equally effective and can be used in combination with methotrexate. Failure to respond occurs in 30% of patients and for them it is worth trying another drug in the same class or a non-TNF inhibitor.

Table 9.6

Currently available TNF inhibitors

THE NON-TNF INHIBITORS

These DMARDs inhibit proinflammatory cytokines other than TNF (see

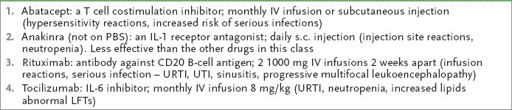

Table 9.7

for a list of currently available drugs).

Table 9.7

Currently available non-TNF inhibitors and side-effects

URTI = upper respiratory tract infection; UTI = urinary tract infection

6.

Local steroid injections are helpful for acute involvement of a joint and may give prolonged relief from pain and swelling and improve function. The main indications for steroid use are:

•

vasculitic complications of rheumatoid arthritis (where high doses are needed)

•

severe progressive disease, until suppressive treatment with another slow-acting antirheumatic drug becomes effective

•

chronic low-dose treatment, which may be justifiable in the elderly.

7.

Surgery may be very effective treatment for severely diseased joints. Hip, shoulder and knee replacements are the most successful operations. Arthroplasty and relief of contractures can be of value, especially in the hands.

The prognosis of this chronic, but often intermittent, disease varies. Only a small minority have no permanent joint problems 10 years after diagnosis, and half have a disability that interferes with work by this time. The greater the number of involved joints at the outset and the more abnormal the inflammatory markers, the worse the prognosis. Life expectancy is reduced by up to 7 years as a result of the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, the increased risk of infection and a threefold increased risk of atherosclerosis. The use of methotrexate has been shown to halve excess mortality, including that from cardiovascular disease.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

This multisystem disorder occurs usually in patients between 20 and 40 years of age. Women are more often affected than men (8:1) and there is an increased incidence in families (monozygotic twins have a 50% concordance). There are associations with HLA-DR2, with HLA-DR3, and with homozygous deficiencies of the early components

of complement. It presents diagnostic as well as long-term management problems. The diagnosis requires at least four of the 11 published criteria either currently or in the past (

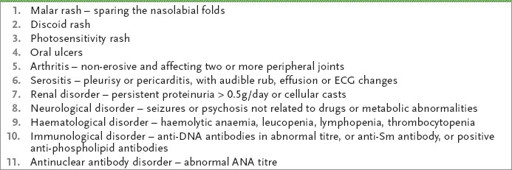

Table 9.8

). Fewer than four criteria are often labelled ‘possible lupus’. Non-specific positive autoimmune tests with some evidence of inflammation can be referred to as ‘undifferentiated connective tissue disease’.

Table 9.8

American Rheumatism Association criteria for SLE

Note:

Four or more manifestations of the 11 must be present serially or simultaneously.

The history

1.

Ask about the presenting symptoms (

Table 9.9

):

Table 9.9

Summary of systems review for SLE

a.

general symptoms – malaise (nearly all patients), weight loss (60%), nausea and vomiting (50%), thrombosis of veins or arteries (15%)

b.

musculoskeletal symptoms (95%) – arthralgia, arthritis (typically symmetrical and non-erosive), myalgia and myositis

c.

dermatological symptoms (85%) – skin rash, alopecia, oral and nasal ulcers

d.

fever (77%)

e.

neuropsychiatric symptoms (60%) – delirium, dementia, convulsions, chorea, neuropathy, loss of vision (optic neuritis), stroke, headache, symptoms resembling multiple sclerosis, anxiety and depression

f.

renal tract symptoms (50%) – haematuria, oedema, renal failure (just about any type of glomerulonephritis)

g.

respiratory tract symptoms (45%) – pleurisy

h.

cardiovascular symptoms (40%) – pericarditis, myocarditis, valvular lesions, premature coronary artery disease (increased atherosclerosis)

i.

haematological symptoms (50%) – lymphadenopathy, anaemia

j.

gastrointestinal symptoms (30%) – nausea, diarrhoea, pseudo bowel obstruction, perforation

k.

thrombophlebitis, recurrent abortions or fetal death in utero (suggests antiphospholipid syndrome)

l.

sicca symptoms (secondary to Sjögren’s syndrome)

m.

reduced activities of daily living and ability to work as a result of the effect of this chronic and relapsing disease on the patient’s life.

2.

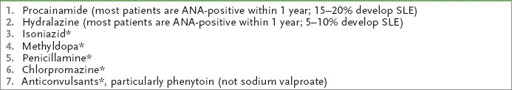

Ask about any drug history (e.g. procainamide, hydralazine) (

Table 9.10

). Remember, newer antiarrhythmic and antihypertensive drugs have made classical drug-induced lupus less common and typically the symptoms resolve rapidly with cessation of the drug; autoantibody levels (anti-histone) diminish slowly. Anti-TNF drugs can also cause a lupus-like syndrome with a positive ANA and anti-double-stranded DNA; minocycline and hydralazine do this too, but with these drugs ANCA (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) is positive as well.

Table 9.10

Drugs inducing SLE

Note:

There is an increased incidence of drug-induced lupus in slow acetylators who will develop a positive ANA and clinical manifestations sooner than rapid acetylators. Drug-induced lupus is more common in the elderly because of the more frequent use of drugs in this group. There is usually no renal or nervous system disease, no antibody to dsDNA, and improvement may occur if the drug is withdrawn.

*

Rarely cause overt SLE, but ANA is commonly positive.

3.

Ask about any treatment given and any complications of treatment.

4.

Ask about problems during pregnancy and use of contraception.

5.

Enquire about the family history.

6.

Enquire about the patient’s understanding of the implications of this chronic and incurable disease and its prognosis.

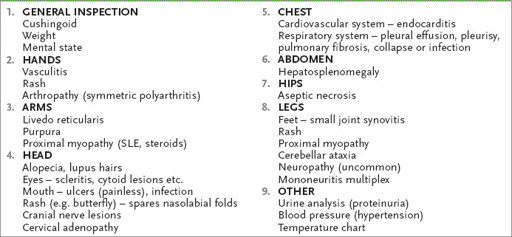

The examination (see

Table 9.11

)

Table 9.11

Systemic lupus erythematosus

1.

Inspect the patient for weight loss and Cushingoid appearance (because of steroid treatment) and assess the patient’s general mental state.