Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (33 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

When you extrapolate this over numerous brokerage firms that are each borrowing, lending, and recalling shares from one another as the underlying shares switch owners, often rapidly, the clearing system can get behind and a good pile of failures to deliver can develop. This can happen without anyone naked shorting, manipulating or creating counterfeit shares and so forth. This happens more in stocks where there is a great interest in selling them short, because it is harder for the clearing brokers to find substitute shares to borrow when faced with a recall request. If there is a problem in the system, Byrne should point his finger at someone other than “miscreant” hedge funds.

His real beef, though, is that some hedge funds figured out that his business model was no good and his stock overvalued. He has made a huge effort to force the shorts to cover. Overstock’s stock price was $43 on August 11, 2005, the day he announced his lawsuit. The stock hasn’t seen that price since and fell to $13 by November 2006. Too bad we weren’t short.

Byrne professes to have no issue with “legal” shorting or hedge funds. Sure. It burns Byrne that short-sellers have made money betting on his failure. The Byrne performance reminded me of something Warren Buffett once told me about the difficulty of shorting the stocks of companies run by crooks, because they’ll fight dirty to save themselves. “The crook’s life depends on it,” Buffett said. While I am not calling Byrne a crook, his made-up rant about me indicates his dishonesty.

In September 2005, nine months after Allied announced the criminal investigation, the U.S. attorney’s office in Washington, D.C., invited us to share our information about Allied to assist their investigation. I went to Washington in October to present the federal prosecutors with a fifty-page slide show. In a cramped conference room, I met for eight hours with Assistant U.S. Attorney Jonathan Barr and another prosecutor and three FBI agents. It was plain that they had done a fair amount of work and were well prepared. At various points, they even referred to my testimony to the SEC. They asked devil’s advocate–type questions, repeating what Allied’s lawyers were obviously telling them in defense.

We went through all Greenlight’s problems with Allied, including its numerous false and misleading public statements, the history of ten separate investments it valued without reasonable basis, how it changed its accounting, and how its valuations still lacked any reasonable basis. We also discussed BLX’s fraud, the loan-parking arrangement, and the oral agreement. We went through Kroll’s findings and Allied’s various attempts to manipulate the market through the rights offering and other efforts. We finished with a discussion of my phone records and a few other Allied misdeeds.

Several months earlier, the FBI agent in San Diego told me he had discovered who obtained my phone records, though he could not tell me who it was. Now, I learned the Department of Justice transferred the investigation to Washington, D.C., where it was in the hands of the team investigating Allied. I could draw my own inferences about who obtained my phone records. The prosecutors and agents took notes and seemed smart, serious, and capable. I left feeling optimistic.

CHAPTER 25

Another Loan Program, Another Fraud

BLX’s loan fraud didn’t stop with the SBA 7(a) program. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) guarantees Business and Industry Loans. The USDA’s Rural Business-Cooperative Service runs the loan program, which guarantees about 75 percent of the loan value. The loans are intended to help develop rural areas and increase employment, improving the economic and environmental climate in rural communities. Like the SBA, the USDA allowed unscrupulous lenders to abuse the program and does not provide enough oversight to catch them.

BLX underwrote a $3 million B&I loan to Bill Russell Oil in June 2000. Like Bill Walton of Allied, the Bill Russell referenced is not a retired basketball star. (Brickman is still looking for a Kareem Abdul-Jabbar loan fraud.) The company, an oil-and-gasoline distributor in Rector, Arkansas, operated gas stations in southeastern Missouri and northeastern Arkansas. By June 2000, it already had about $1 million in loans to other creditors. The EPA cited Bill Russell Oil for numerous violations concerning fuel storage and ordered a cleanup. Bill Russell Oil was supposed to use some of the proceeds of the BLX loan to correct the violations. The company had weak collateral and virtually no prospects of paying the BLX loan back or even making interest payments. In November 2000, BLX made a fresh $400,000 SBA 7(a) loan to the company. Almost a year to the day after BLX made the USDA loan, the USDA paid out its guarantee. The SBA paid on its guarantee on the smaller SBA loan in November 2001, though the SBA data indicates that the agency was eventually repaid in full.

Bill Russell Oil ignored the EPA demands to comply with its environmental rules and did not return the agency’s phone calls. The Justice Department eventually filed a complaint. In April 2005, the District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas granted a judgment against the company for $83 million. This triggered an audit of BLX’s loan by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) of the USDA.

In September 2005, the USDA issued a forty-page audit recommending that BLX repay the guaranteed amount of the loan and be kicked out of the Business and Industry Loan program. (The audit at

www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/34099-07-TE.pdf

does not name BLX or Bill Russell Oil. Instead, it refers to them as the “lender” and the “borrower,” respectively.) The audit report describes the kind of behavior that Kroll, Carruthers and Brickman found on many of BLX’s SBA loans. In particular, the auditor found that BLX misrepresented the value of the borrower’s property. For example, when the borrower obtained an appraisal of the collateral, the appraiser noted that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had closed several of the stations and that the agency had required upgrades at the properties. When the appraiser asked the company to provide documents to better determine the value of the properties, the borrower said it could not because its records were destroyed in a fire. The appraisal in March 1999 came in at $1.5 million, which wasn’t enough for a $3 million loan.

“We concluded that the lender misrepresented the value of the 20 properties to the state office by concealing the March 1999 appraisal,” the report said. “State officials said they would not have guaranteed the loan if the March 1999 appraisal had been made available prior to issuing the loan note guarantee.”

Instead, according to the report, BLX recommended a different appraiser, who reappraised the properties at $4.3 million. Presto! There was now enough collateral for the loan. However, the $4.3 million appraisal assumed a value based on property improvements that had not been made. BLX was responsible to verify the improvements and did not. In fact, the new appraiser certified that some of the properties had already been upgraded, and he included a list of these improvements in the appraisal report. He also said he had seen reports on the properties that said the environmental concerns were minor. When later asked by the OIG auditor to provide these reports, the appraiser said he could not find them.

The audit also found that six months before the loan closed, the state of Missouri revoked the borrower’s motor fuel license, and two months before the loan closed the EPA inspected some of the properties and found more than sixty violations. Despite these events, BLX certified that no major changes had occurred.

In addition, the audit found that BLX misrepresented the condition of the properties. BLX knew that the borrower had not only failed to upgrade nineteen of the twenty properties, but that several were not even open at the time the loan closed. BLX falsely certified that the upgrades had been made and that 95 percent of the properties were operational.

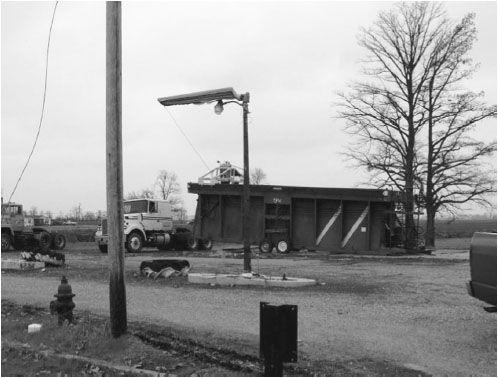

The most striking parts of the audit were photographs of properties that showed buildings that were just shells, falling apart and abandoned. The pictures revealed that there was little chance these properties were operational in the recent past, as BLX certified. For example, a tornado damaged a property in Missouri a month before the loan closed. It’s hard to tell in the photo, but a building might have once stood on the site (see

Figure 25.1A

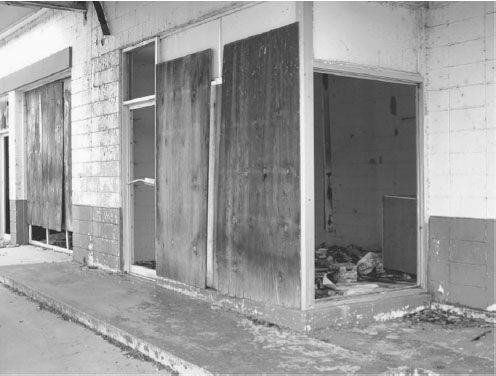

). Another Missouri property had been declared unfit for human occupancy a week before the loan closing (see

Figure 25.1B

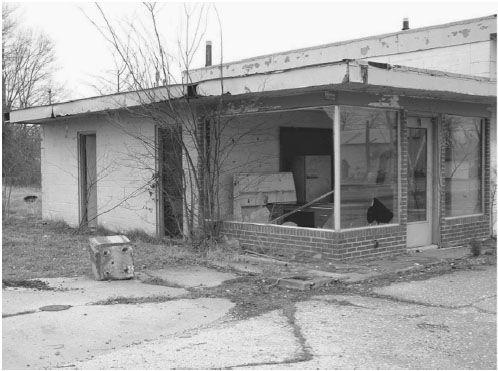

). Another photo showed an abandoned, falling-apart gas station in Missouri that neither BLX nor the borrower could prove was operating at closing (see

Figure 25.1C

). One other building in Arkansas was shown in similar condition, also with no proof that it was operating when BLX closed the loan (see

Figure 25.1D

).

According to the report, in a 2005 meeting with BLX, CEO Robert Tannenhauser told the inspector general’s office that he was not aware if anyone ever visited the properties before the loan closed. Two BLX vice presidents attended the meeting, but they were recent hires and didn’t know much about the loan. The vice president who processed the loan was no longer with BLX, and that officer, through his lawyer, said he wouldn’t talk to the OIG.

Finally, the report found that loan proceeds were siphoned off for impermissible purposes. Part of the proceeds went to a loan arbitrator who had negotiated down Bill Russell Oil’s existing debt. BLX paid the arbitrator out of the B&I loan proceeds, which is not allowed under the program’s rules. “In a fax to the arbitrator, dated December 20, 2000, the lender’s loan officer wrote that he had stuck his neck out to pay him the initial $75,000,” the auditor’s report said. Nowhere in the loan documents was this payment listed. “The lender knew this was not an authorized use of loan funds.”

After the loans went bad, BLX ordered another appraisal in 2002 so it could liquidate the properties and get some of the money back. That appraisal came in at $1.2 million, much closer to the first appraisal.

The OIG audit recommended that BLX pay back the $2.4 million, plus accrued interest, that the USDA paid on its guarantee, and that BLX be debarred from the B&I loan program. Debarment from one government lending program would automatically prevent BLX from participating in any other government loan program. So debarment would disqualify BLX from the SBA program as well. The USDA did not agree with the OIG’s debarment recommendation and suggested that debarment should only be used as a threat to ensure BLX reimbursed the loss.

In February 2006, Brickman tracked down the USDA auditor of the Bill Russell Oil loan. The auditor told Brickman that BLX’s attorneys in Little Rock wanted to form a marginally funded corporation to purchase at a tax auction the twenty contaminated properties discussed in the audit. That way, if litigation arose about pollution cleanup or health claims, the liability would fall on the marginally funded corporation, which would simply go bankrupt and cease to exist. All the damages, liabilities and other charges would not show on Allied or BLX’s financial statements. The auditor said the “SEC was very concerned about this proposal.”

One would think that after discovering an enormous fraud like this, the USDA would look into other loans by the same lender. It doesn’t work that way. After we discovered the Bill Russell Oil fraud, Brickman obtained information on all of BLX’s B&I loans from the USDA under FOIA.

Brickman found that BLX made B&I loans to gas stations, truck stops, a butterfly pavilion, a mushroom company, a sports emporium, a general store, a paper-box manufacturer, an ice skating rink, and others. Of the roughly fifty loans that BLX made under the USDA program from 1998 to 2003, the USDA paid guarantees on more than 42 percent of the loans totaling $41 million. However, as was the case with the SBA loans, only two loans had been charged-off, suggesting an unusually slow loan workout process. Brickman searched for news on the other loans and found a number of borrowers filed bankruptcy or showed clear evidence of default. This brought the total of identified problem loans to an astounding 65 percent of BLX’s portfolio of USDA loans.

Brickman compiled a lengthy summary of several defaulted USDA B&I loans and gave them to the USDA auditor. Brickman showed evidence that USDA loans were used to bail out other lenders, thereby transferring losses from private lenders to taxpayers. He found that BLX made loans to people who had previously defaulted on USDA loans and made USDA loans that bailed out SBA loans. BLX passed defaulted loans from one government agency to another.