Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (35 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Instead, Allied provides its own valuations to Duff & Phelps for review. For about $5,000 a company, Duff & Phelps looks at Allied’s work and without independently checking facts it provides a “negative assurance”—meaning that

assuming that the information Allied provided is accurate and complete, Duff & Phelps advises that the valuations are not unreasonable.

Of course, if Allied management picks and chooses which facts it shares with Duff & Phelps, its valuation consultant has no basis or authority with which to disagree.

At only $5,000 per company, Duff & Phelps is not being paid enough to do a sufficient amount of work and research. Appraisals would probably cost at least ten times more. Indeed, according to its standard agreement Duff & Phelps performs only “limited procedures” of reading and discussing management’s prepared valuations and related write-ups, meeting with the deal teams to understand management’s expectations and intent for each investment and to discuss the underlying company’s strategy and performance. It considers general economic and industry trends, publicly traded comparable companies, the financial information provided by management and “other facts and data that are pertinent to the companies as disclosed by management.” Duff & Phelps checks management’s calculations for clerical accuracy. Finally, it speaks with auditors and underwriters about “any questions they may have regarding the limited procedures.”

Though Allied improved the optics of its process, the various red flags such as performance smoothing and serial correlations of the valuations persisted. We had sufficient information about several of Allied’s investments to know that Allied still valued them at prices for which it had no reasonable basis. Of course, as long as the mother ship of misvaluation, BLX, continued, there was little reason to take the “valuation assistance” too seriously.

We did brokerage business with JMP Securities, one of the firms Allied retained to assist in the valuation of BLX. I called Greenlight’s salesman at JMP and asked to speak with whoever was doing the work on Ailled. JMP refused. I offered to do it on the basis that I would speak and JMP would only have to listen. Again, JMP declined. The JMP salesman noted, “We aren’t saying to buy Allied stock, you know.”

Allied’s results were getting weaker. The company distributed more per share than it reported in earnings in 2003 and 2004. Net investment income (excluding gains and losses) was $1.65 per share in 2003 and $1.52 per share in 2004. Supported by Allied’s strategy of selling winners and keeping losers, taxable earnings were $2.40 per share in 2004 and the related tax distributions were $2.30 per share. Net income, which included unrealized losses, was only $1.88 per share. In the fourth quarter of 2004, Allied modestly reduced the carrying value of BLX by $26.1 million, nowhere near to what it should have valued it, since originations fell 30 percent from the prior year.

In the first quarter of 2005, Allied converted $45 million of its loan to BLX into equity to “strengthen the capital base” and “clean up the capital structure.” As mentioned, Allied stopped providing detailed financial information on BLX at that point, so it became harder to track. Nonetheless, converting debt to equity is not usually a good sign, because it indicates the company isn’t creditworthy enough to support the debt.

The regulatory investigations also started to create large legal expenses in 2005. In the first half of the year, Allied spent $25 million. Assuming legal fees of $300 an hour, you can employ fifty lawyers for sixty hours a week to run up a legal bill that high. In the third quarter the expense fell to half as much and to “only” $3.6 million in the fourth.

Allied had two home runs in 2005. First, it sold its entire portfolio of commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and its platform for originating CMBS to a Canadian bank for a large gain. Second, Allied made an initial small investment in 2001 in Advantage Sales & Marketing, which became a large investment when Allied rolled a number of regional competitors together in 2004. It announced a sale of the rollup for a very large gain in 2005. The combined result led to earnings per share of $6.36.

After raising the quarterly tax distribution a penny to $0.57 per share two quarters after my speech, Allied held it flat at that level for nine consecutive quarters. Given the investment performance and ever disappointing recurring net operating income, it was enough of a charade to maintain the quarterly $0.57 distribution. Now, aided by the two large realized gains, Allied began, again, to slowly raise the distribution, generally by a penny per quarter.

However, Allied found much greater competition to make new loans and reduced the interest rates it charged for the loans. The yield on its portfolio fell. Further, the $36.4 million of investigation-related costs were a headwind. Net investment income fell, again, to only $1.00 per share in 2005.

Even so, the realized gains created so much taxable income that Allied was left with a dilemma. If they paid out all the taxable income, even as a special distribution, it would be hard to have visibility on future distributions. Obviously, recurring net investment income was now much less than the distributions. Further, Allied had harvested its best gains and it wouldn’t make sense to stake the future stability of the distributions on the relatively barren portfolio. If you pick your flowers and water the weeds, you wind up with a garden of weeds.

To solve this, Allied used a rule in the tax code that permitted them to defer distributing the taxable income to shareholders for a year by paying a 4 percent excise tax. Of course, this made no economic sense. Had they paid the distributions, the shareholders would pay long-term capital gains tax at a 15 percent rate on the income. Effectively, the 4 percent excise tax was a 26 percent interest rate one-year loan. (Shareholders were deferring paying a 15 percent tax for one year. The cost was 4 percent—paid by the company: 4/15 = 26.6 percent). For that cost, Allied was able to avoid paying out a special distribution. Instead, its shareholders had to wait a year to receive their money as part of the normal quarterly distributions. In fact, when Allied told the shareholders that it created this rainy-day reserve fund to give added visibility for future tax distributions, the shareholders, focusing on regular quarterly “dividends,” cheered.

A side benefit of the spillover distribution was the complete transition of the business from being operating-earnings driven to capital-gains driven, and finally to paying the distribution out of an earlier year’s capital gains. With operating earnings no longer relevant, Allied lost most of its incentive to control its operating costs. Consider

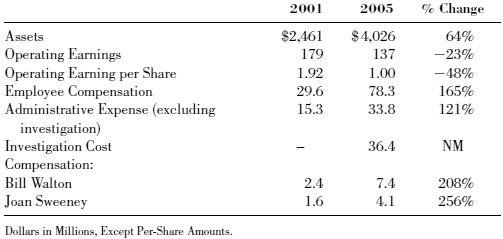

Table 26.1

, comparing results in 2001, the last year before my speech, and 2005.

Table 26.1

Allied Operating Results

Operating earnings have fallen in absolute dollars, as a percent of assets and on a per-share basis. This is true, even if you back out the investigation costs. Meanwhile, employee and administrative expenses, excluding the investigation costs, have grown much faster than assets. But growing fastest of all: senior management compensation.

CHAPTER 27

Insiders Getting the Money Out

Allied might have felt that it was being protected by its friends in Washington, but that’s a big assumption to make when millions of dollars are at stake. There was no way to be sure that all the influence would derail regulators and their investigations. And if regulators did take action, some senior executives at Allied who were rich “on paper” would become much less so.

In April 2006, as part of Allied’s announcement of its upcoming annual meeting, it told shareholders in its proxy that they would be voting on details of a misleadingly named employee “stock ownership initiative” during the meeting. That might have sounded innocent to shareholders, because companies are always amending these plans and shareholders are always approving them. It sounded almost boilerplate. But this one was different and not so innocent.

Allied’s officers and senior employees hold millions of dollars’ worth of stock options, given to them as part of their compensation. Allied’s officers had to know that there was a real possibility that the various government investigations could lead to serious consequences, causing the stock to plummet and the value of those options to vaporize. They had a better sense of the status of the investigations than public market participants. For a year and a half, they refused to comment beyond standard disclosures prepared by their lawyers. If Allied executives knew of any material bad news in the investigations (or bad news anywhere in the business) and they exercised their options and sold before that news became public, they could later be accused of civil, or even criminal, insider trading.

Many of the employee options were “in the money,” meaning the price at which employees could exercise them was below the price of the stock. Allied’s outstanding options had an average exercise price of about $22 at the end of 2005, so, for example, if the stock were trading at $30, employees could exercise the option to buy the stock at $22 and immediately sell the shares on the market for $30, making about $8 a share in profit. Allied’s executives were poised to make hundreds of thousands, and in some cases, millions of dollars, from their options.

Exercising the roughly thirteen million vested, in-the-money options that were outstanding, and then selling the stock en masse, would drive down the price of the stock. Allied’s stock is not tremendously liquid and usually only a few hundred thousand shares trade a day. Each sale would require the executive to file a Form 4 with the SEC and disclose the sale within a day or so. A big part of the confidence story Allied and its supporters advanced in 2002 was, “If there was fraud, insiders would be selling.” The company’s line was that since executives weren’t selling—and, in fact, they made symbolic purchases of trivial numbers of shares to signal the market with news of insider buying—everything must be fine.

Large insider sales would make news immediately, and Allied couldn’t allow that. The quandary for senior executives was how to get their money out without risking insider trading accusations and also without pushing down Allied’s stock with news of their sales. After all, CEO Walton held about $24 million worth of options at the end of 2005, and COO Sweeney held about $12 million. They would be the two top beneficiaries of the proposed plan.

So Allied proposed a stock ownership initiative whereby employees with vested in-the-money options could tender them to the company in exchange for their value paid half in stock, half in cash. Because the company was near the legal threshold in the number of options it could issue (the law caps BDC’s at 20 percent of outstanding shares; Allied was at 18 percent), the company said canceling existing options would make more available to employees and new hires. According to the proxy, “Stockholders are not being asked to approve the stock ownership initiative. Stockholders are being asked to approve the issuance of shares to satisfy the common stock portion of the OCP (option cancellation payment). Should stockholders not approve the issuance of shares, the Board of Directors may elect to revise the composition of the OCP to an all cash payment,” the company said, in what sounded like a threat. Obviously, if the payments were all cash, then

the employees would not receive any stock as part of the stock ownership initiative

.

I have never seen a plan like it. I asked around and couldn’t find anyone else who had seen a plan like it, either. This program would effectively enable insiders to sell up to $397 million of stock back to the company without burdening the open market with millions of shares of insider sales. Why would anyone want to buy 9.5 percent of the company’s outstanding shares from the employees? “What do they know that we don’t?” the market would ask, assuming the worst.

Also, because the sales would be to the company, there would be no presumed information disadvantage that insiders held over other shareholders. So, if management foresaw a bad ending to the investigations, they might not be held liable for insider trading in the same fashion as if they’d exercised their options and sold in the open market.

Based on our analysis of the proxy, if everyone participated, about thirteen million vested in-the-money options would be exchanged for 1.7 million shares and $53 million in cash. Prior to the exchange, if the stock rose a dollar, employees would be $13 million richer. Afterward, they would become only $1.7 million richer. Allied disingenuously asserted that owning 1.7 million shares directly better aligned employee’s interests than owning thirteen million in-the-money options. Dale Lynch, who had taken over as head of Allied’s investor relations, told

The Wall Street Journal

, “We think this is a very elegant, transparent way to get stock into the hands of employees.” Again, opacity as transparency.

On the downside, executives would be protected. With stock options, if the price falls below the exercise price, the options have no intrinsic value. After the deal, employees would get to keep the $53 million in cash and the shares wouldn’t become worthless unless the stock hit zero. This plan would actually reduce the insiders’ exposure to the stock, not increase it.

Cue a joke from my dad’s book: A fellow owned a bar. One day he noticed that every time his bartender sold a drink, he would put one dollar in the cash register and one dollar in his pocket. Several months passed. The owner came back to his bar. This time he noticed that when the bartender sold a drink, he put nothing in the till and both dollars in his pocket. The owner went up to the bartender and asked, “What’s wrong, aren’t we partners anymore?”

As I see it, the tender offer only made sense as a clever maneuver by senior executives to get their money out before the stock collapsed. Allied was on the ropes, and this proposal showed me that the people running the company knew it.

In September 2006, Hewlett-Packard chairwoman Patricia Dunn was accused of spying on other board members because she was concerned about leaks. She launched an investigation that included obtaining the phone records of board members by private investigators impersonating the members to their phone companies. This was called “pretexting” because somebody calls and pretends to be somebody else to obtain the records.

Now I knew the name for what happened to me and to the other Allied critics. As the HP story became national in scope, with Congressional hearings, criminal prosecutions, and high-level resignations, it became clear that this was a crime after all. Given the ramifications of the HP case, I remembered that the brush-off letter response I received from Allied’s board in 2005 did not specifically address the pretexting issue.

I was sure Allied obtained my records and wanted to raise the level of scrutiny on the company’s illegal activity. On September 15, 2006, I sent the board another letter, reminding members of what happened to HP over this issue and urging them to investigate. The letter stated:

The only group of individuals with any motive to access my phone records and the records of four other prominent Allied critics is Allied management. In light of the public outcry and potential criminal indictments resulting from HP’s conduct, the Board cannot pretend that such use of pretexting is not a serious matter. Indeed, the pretexting in this case does not merely concern leaks, but is far more serious. If Allied management was involved in illegally accessing the phone records of its critics, such pretexting constitutes an attempt by the company to interfere with and chill its critics and therefore skew the flow of information which is critical to the securities markets. The Board clearly has an obligation to investigate such criminal conduct by Allied’s management.

We got back another curt dismissal from the new chairwoman of the Audit Committee, saying that it had “looked into your allegations that Allied’s management played a role in an attempt to access your phone records and have found no evidence to support your claim.” I felt that the denial again was weak and the language carefully crafted. What they found was

no evidence

. It wasn’t clear how hard they looked, and it appeared the language avoided the issue of someone hired by the company, such as a lawyer hiring someone else to access my records. Though the response letter offered me the opportunity to provide more information, its tone suggested the board was not that interested in getting to the bottom of this. In fact, my letter already contained enough specifics for the board to know what to investigate, had it been interested.

After much consideration, we decided to raise the profile of the story to get Allied to take this more seriously. We reached out to

The New York Times

, which ran an article on November 8, 2006, describing our accusations that Allied engaged in pretexting. The article, written by Jenny Anderson and Julie Creswell, discussed the Allied critics who claimed they were victims of pretexting and the company’s denial that it was responsible. The article stated:

The allegations, made by Mr. Einhorn in two letters to Allied’s board—one letter was sent as recently as September—suggest that getting the phone records under pretext may have been an effort to root out relationships and silence critics. . . . A spokesman for Allied said the company had no comment on the claims of pretexting, beyond its responses to Mr. Einhorn.

The New York Times

article ran the day Allied announced its third-quarter 2006 earnings. On the conference call, Walton criticized me again:

Before we wrap up, I’d like to comment on

The New York Times

article, which some of you may have seen, that ran in today—this morning’s paper. As most of you know, probably all of you know, for the last four and a half years, David Einhorn, an investor with the short position in Allied Capital, has made a variety of accusations about Allied Capital. Our performance has proven his thesis to be very wrong. David’s motives are simple; he makes money if he can drive down the price of Allied Capital stock. We believe today’s story is yet just another example of Mr. Einhorn’s tactics. With respect to today’s article regarding accessing phone records of Einhorn and other Allied critics, David’s written twice on this same topic. The first time that Einhorn raised an issue regarding access to phone records was in a letter to Allied board members in March 2005. Within a week the chairman of Allied’s Audit Committee responded in a letter to Einhorn, indicating that the board had not seen evidence to support his accusations, but would evaluate any evidence of wrongdoing that he wished to provide.

Mr. Einhorn never produced any evidence to support his accusations. Eighteen months later, after pretexting became big news, Mr. Einhorn provided yet another letter regarding the alleged access of phone records. In this letter he clearly attempts to capitalize on the recent media scrutiny involving Hewlett-Packard and that he’d be happy to provide the board with additional information that will be of assistance. These are his words. On September 29th, Allied’s chairman of the Audit Committee responded to Mr. Einhorn in a letter. In that response the chairman indicated that the board looked into Einhorn’s allegations and found no evidence to support his claim of management misconduct with respect to phone records. The board then requested once again, that he supply any evidence of wrongdoing. To date, he has not responded. Twice our board has written to him that his allegations are not supported by the facts, and twice our board invited to provide evidence of wrongdoing. Twice he has provided no information.