Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (50 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Prior to the mediation, the DOJ sent a letter explaining to Allied that it could be held accountable for the false claims, yet the DOJ chose not to pursue any recovery directly from Allied. Gerald Sachs told us Allied was in a precarious financial position, and it was unclear whether it would be able to satisfy a large judgment even if it were found liable. The DOJ accepted no responsibility for the years that it had sat on the sidelines while Allied melted in value, nor did it consider that Allied was nonetheless about to be sold for hundreds of millions of dollars.

We argued as hard as we could against the settlement. After we made our case, the DOJ informed us it would “not re-open the settlement negotiations.” It appeared to us the DOJ was afraid reopening settlement discussions or unsealing the case would delay or even derail Allied’s proposed sale.

We arranged a final meeting with the government in Atlanta in February 2010. Sachs said the government had “thoroughly investigated the case.” There were more than 12 informal interviews of former Allied and BLX executives and many documents reviewed. The government was ready to settle.

Glenn Harris from the SBA was present again, and pointed out certain weaknesses he thought we had in the case. He said we would have to show that the loans were “not prudent” and that it might be hard to show that BLX knew it wasn’t acting prudently. I questioned how the government could have people sitting in jail because of loans that it was no longer convinced could be proven to be imprudent. Sachs said that “the standards are different” and the government might have a harder time proving imprudence on some loans than on others.

The government would not pursue damages against Allied, because it said it hadn’t found evidence that Allied made any of the loans itself.

We asked what investigation they had done into Allied’s responsibility. The government refused to answer. We asked whether the government questioned Robert Tannenhauser or any of the Allied officers who served on BLX’s board. The government refused to answer.

Sachs’s boss, Amy Berne, told us, “Keep in mind we don’t have to run this investigation the way you want us to.”

Brickman replied, “You had a smoking cannon and no one was even willing to look.”

Berne, who could barely contain her dislike of us, threatened, “In a minute, I am going to say that only attorneys can speak.”

We thought this original

qui tam

case stood a better chance of surviving than the shrimp boat case. A year earlier, to our disappointment, the appellate court had rejected our appeal of the shrimp boat case dismissal in a one-page ruling that found that our case relied “entirely” on publicly available information. In this original case more of the information came from the nonpublic BLX delinquency report, the Kroll investigation, and the information the government obtained from BLX that it showed us. However, in January 2010, the appellate court dismissed a relator in another case and ruled that relators that relied on publicly disclosed information “in any part” could be dismissed from cases. Effectively, the court simply inserted this new language into the statute. Under this standard, we stood practically no chance of surviving an effort to exclude us from the case.

Sachs cited the recent ruling and told us that if we didn’t settle, the defendants would seek to have us dismissed from the case.

Berne advised us, “You guys should settle.” When our lawyer asked one last time whether they had interviewed the top three people—Tannenhauser, Walton, or Sweeney—Berne replied, “It will be this or nothing for you.”

Rene Booker, a senior DOJ lawyer from Washington, D.C., finished by telling us that this was one of thousands of

qui tam

cases they see. The investigation of this one was complete and they had “used an excessive amount of resources already.” She pointed out, “If you think it has been difficult to deal with you, it has been harder to deal with the defendants,” and the DOJ would push the settlement “with or without you.”

The DOJ had tried to justify the low settlement by performing a so-called risk analysis, where it handicapped its chances of winning and chances of collecting if it won. The risk analysis made little sense to me, as it seemed that every assumption was lowballed in order to justify a low settlement. It even included a substantial “collectability” discount for the money the DOJ had already collected from BLX. I decided to take one last shot at arguing the analysis:

I pointed out that of the $26.4 million in the settlement, BLX had already paid or escrowed all but $8.2 million so there was little downside risk if the government litigated the case. If one compared that to the potential trebled damages if it won, the government was settling the case for only 2 to 3 percent of the possible recovery. I said, “I just don’t understand the risk analysis here. You are only risking $8.2 million if you lose, but could get hundreds of millions if you win.”

They were unimpressed.

Sachs pointed out that

Allied’s lawyers

and the mediator gauged the possibility of prevailing against Allied at zero. Booker added that the government has “settled much better cases than this one.” Harris concluded, “You are looking at this as an investor, gambling $8 million versus hundreds of millions. We can’t look at it this way.”

Sachs asked whether anyone had any other questions.

A couple of weeks later, we decided that we had done the best we could, and as distasteful as it was, we took the deal on the table. The documents were signed just in time for Allied to complete its sale to Ares.

CHAPTER 39

Some Final Words to and from the SEC

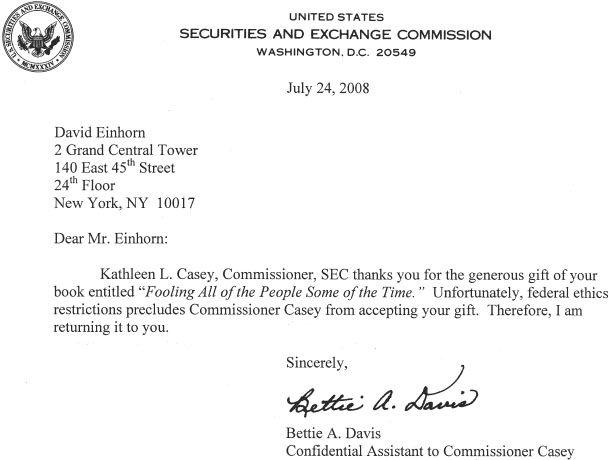

Upon its publication in May 2008, I sent copies of

Fooling Some of the People

to many influential Washingtonians, including elected officials and the SEC commissioners and lawyers. A few weeks later, I received a FedEx package with this note:

She didn’t even get the title of the book correct.

I received two other returned copies with similar personal notes about “gifts” worth in excess of $20 from SEC Enforcement lawyers. In retrospect, I should have marked the packages “EVIDENCE.”

In March 2009, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report to Congress regarding the overall performance of the SEC Enforcement division. The report validated many of the conclusions of this book and indicated that problems at the agency were both widespread and deep. The report summarized that in 2006 and 2007, the SEC revised its policy on penalties to focus on the direct benefit a corporation gained through its misconduct, and whether a penalty stands to cause additional harm to shareholders. As a result, penalties fell 39 percent in 2006, another 48 percent in 2007, and another 49 percent in 2008. This left penalties in 2008 down a cumulative 84 percent from 2005. According to the GAO, “We found that Enforcement management, investigative attorneys, and others concurred that the 2006 and 2007 penalty policies, as applied, have had the effect of delaying cases and producing fewer and smaller corporate penalties.” The report concluded, “A number of investigative attorneys told us that because the policies, as applied, created a perception that the SEC had retreated on penalties, defendants or potential violators have become more confident or emboldened.”

The philosophical and, perhaps, political bias against penalties was so great that in one case where a company actually proposed a settlement with a higher penalty than the Commission would approve, the SEC required its attorney to return to the company and explain that the Commission wanted a lower amount.

The bias also discouraged Enforcement attorneys so that recommending no penalty at all was the path of least resistance. This covered the period when Allied claimed vindication precisely because the SEC inflicted no monetary penalty for its misconduct.

Instead, the GAO report outlined that the SEC’s priority was to spend its time and attention on small-fry defendants that, unlike Allied, could not spend tens of millions of dollars of shareholder money on politically connected lawyers and lobbyists to defend itself. The GAO cited one expert’s opinion that the agency’s Enforcement attorneys “focus on modest cases like small Ponzi schemes, insider trading and day trading, because such cases were thought to stand a better chance of winning Commission approval, compared to more difficult and time-consuming cases like financial fraud.” Tell that to the Allied shareholders whom the SEC was charged to protect.

In December 2007, the SEC replaced its Inspector General. Upon publication of the hardcover edition of this book, SEC Chairman Christopher Cox’s Chief of Staff asked the SEC’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) to review our complaint against Mark Braswell, the former SEC Enforcement lawyer who took my testimony in 2003 and then, after leaving the SEC shortly thereafter, registered as a lobbyist for Allied.

On July 10, 2008, the SEC-OIG opened an investigation captioned “Allegations of Conflict of Interest, Improper Use of Non-Public Information and Failure to Take Sufficient Action against a Fraudulent Company.” The OIG broadened its investigation to include additional allegations made in this book.

On March 9, 2009, I testified in the investigation at Greenlight’s office. The investigation was completed on January 8, 2010.

The Washington Post

obtained a redacted copy of the 69-page report and ran a story about it on March 23, 2010, which contained a Web link to the redacted report. Most of the redactions concealed the identities of government officials, Allied employees, and Allied’s lawyers. My lawyer’s identities and my identity were not protected.

I question whether it is good policy to hide the identities of these individuals. As there is no penalty for the wrongdoing described in the report, the least the government should do is identify who did what so that we can hold them publicly accountable. To the extent I have determined the redacted identities, I have included them in the discussion that follows. (This redacted report—and, if we ever receive one, an unredacted report—is posted at

www.foolingsomepeople.com

. We are trying to obtain an unredacted copy of the report and exhibits through the Freedom of Information Act. In September 2010, six months after our initial request, the SEC granted access to 14 of the 92 exhibits. These 14 were all documents that were already public, including our analysis of Allied that we had posted on our web site in 2002—on which the

SEC redacted Doug Scheidt’s name

.)

- Serious and credible allegations against Allied were not initially investigated, and instead Allied was able to successfully lobby the SEC to look into allegations against its rival (me) without any specific evidence of wrongdoing.

- Very soon after Enforcement began looking at the allegations made against me, they concluded there was no credible evidence to demonstrate that the activities of Greenlight violated any federal securities laws. Although the investigation was completed by mid-2003, it was not formally closed until 2006 and I was never informed that I was no longer a subject of investigation.

- My claims against Allied were validated to a great extent by the Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations (OCIE).

- The OCIE examiner was concerned that the manner in which Allied was financing its dividends was akin to a Ponzi scheme.

- The OCIE referred its findings to Enforcement, which never investigated how Allied financed its dividends.

- Enforcement determined by mid-2006 that more than a dozen of Allied’s investments had significant problems with the calculation of their values and that Allied had materially overstated its net book income on SEC Forms 10-K for several years.

- Enforcement considered fraud charges against Allied and a redacted Allied officer, whom Enforcement found to have overvalued some of Allied’s investments.

- Allied’s high-powered lawyers, including Bill McLucas, a former director of Enforcement at the SEC, successfully lobbied for a settlement of a “books and records” charge.

- Mark Braswell, who had such significant performance problems that he was asked to leave Enforcement, was able to obtain a significant amount of sensitive information that he might have disclosed to Allied when he became a registered lobbyist for the company only a year after leaving the SEC.

The OIG wrote, “We found concerns with both the OCIE examination of Allied and the resulting Enforcement investigation and believe there are questions about the extent to which Allied’s SEC connections and aggressive tactics may have influenced Enforcement’s and OCIE’s decisions in these matters.”

That summary confirmed what I had long suspected, but the details in the report were far worse than I imagined.

In June 2002, Joan Sweeney and Bill McLucas, representing Allied, met with Doug Scheidt and a current member of Enforcement. Scheidt told Allied that he did not agree with Allied’s white paper about its accounting that said that it was difficult or impossible to apply the SEC’s accounting guidance to a BDC portfolio. Shortly after that meeting, Allied removed its white paper from its web site. (If this is in fact the meeting referenced at the end of Chapter 9, it confirms that Allied misrepresented the gist of the meeting in its subsequent press release.)

Scheidt believed that Allied should be investigated. A group from Enforcement took a look and decided not to act. That group was tasked to bring “real time” enforcement cases, and the accounting issues with Allied appeared to be too complicated to bring a rapid action.

Scheidt also referred Allied to the Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations (OCIE), which opened an investigation. In a normal examination, three or four examiners spend about a week at the examined firm, interviewing management and reviewing documents. Then they return to the SEC and write a report and, if needed, send a deficiency letter outlining what steps must be taken to come into compliance.

In the Allied examination, only one relatively junior staff accountant was assigned. The SEC never visited Allied even though it was located only 10 blocks away from the SEC’s headquarters. The entire 18-month examination was conducted through letter correspondence. It took a long time because “Allied was not overly cooperative” and, as described later, Gene A. Gohlke, the associate director of the OCIE, caused additional delays. Allied came in 18 to 20 times to “explain” what it was doing.

The staff accountant was supervised very closely by Gohlke. This was a most unusual arrangement, as there were several layers of seniority between them. The staff accountant told the OIG that in her view assigning her, a fairly new employee, signaled, “It was almost like they didn’t want to find anything.” Bless her soul, she decided, “This was a project to prove myself.”

After a period of time, the staff accountant asked for additional help and an examiner was added to the team. They received considerable push-back from Gohlke. Periodically, the two would meet with Gohlke, who conveyed an overall feeling that they were overdoing it. When they voiced their convictions that there was a problem with Allied, Gohlke sent them back to do more work. According to the examiner, this “didn’t undo what we found.”

The report indicated that in June 2003, Gohlke met alone with Allied and came away satisfied with Allied’s answers. As a result, the examiner believed that the OCIE would likely back off from Allied.

According to the examiner, Gohlke knew Sweeney and “indicated that he trusted her and had the view that anyone who had worked at the SEC was ‘not going to be doing anything illegal.’” The examiner testified that Gohlke told her, “Sweeney is a nice person. She used to work here. I know her. She is not going to do anything illegal.” The examiner believed that Gohlke was personally involved in the Allied examination because he knew and trusted Sweeney.

In his testimony, Gohlke did not recall knowing Sweeney and though he may have known she worked for the SEC, he swore he “did not remember” this fact. When confronted with testimony from the staff accountant and the examiner that contradicted him, Gohlke testified he didn’t remember if he knew Sweeney or said those things about her. Gohlke admitted he believes that someone in the industry who used to work at the SEC is more likely to be fair and honest.

After my testimony at the SEC in 2003, Braswell contacted Gohlke, who told Braswell that he did not believe Allied was engaged in wrongdoing, even though Gohlke’s division, the OCIE, had already found evidence of wrongdoing by Allied.

At the end of the 18-month investigation, the SEC never sent a deficiency letter to Allied. As a result, “the people [at Allied] just kept doing what they were doing,” according to the examiner. Both the examiner and the staff accountant believed strongly that Allied had major problems. Gohlke “gave them a lot of push-back about referring it to Enforcement.” The staff accountant testified that after the referral, Gohlke stopped speaking to her for months. Her branch chief told her that she was putting her career on the line by going against Gohlke.

After OCIE referred the case to Enforcement in early 2004, Enforcement conducted an investigation, which supported the concerns of the OCIE. There is a lot of space discussing this investigation in the OIG report, but too much is redacted to know what actually transpired.