Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (23 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

CHAPTER 19

Kroll Digs Deeper

While all of this was going on, Kroll was making significant progress in its investigations into American Physicians Services (APS) and BLX. While Allied revealed nothing about the nature of APS, Kroll discovered APS was a “physician practice management company.” In the late 1990s, Wall Street thought companies that purchased doctor practices and provided back-office services, including scheduling, supply purchasing and billing, were the future of medicine. The problem was that most of these companies didn’t really improve the doctors’ lives and interfered a lot, which caused relations between the doctors and the corporate owners to deteriorate. Once companies got a bad reputation from the doctors, it became harder to acquire additional doctors to meet growth plans. As a result, the stock prices fell, which eliminated any remaining ability to use stock to acquire more doctors. The doctors, who accepted stock up-front to sell part of their practices, became even unhappier. Ultimately, most of these companies, including the industry leader, Phycor, failed. As discussed in Chapter 4, we had seen this happen at Orthodontic Centers of America.

Kroll found that APS fit into this bucket. TA Associates, a well-regarded venture capital firm in Boston, backed APS’s start-up, and Allied provided a subordinated loan. Kroll found that the majority of doctors and former executives interviewed did not believe APS would ever be successful or that Allied would recover its investment. A number of physicians interviewed were unhappy with their relationship with APS, using such words as

incompetent, dishonest,

and

crooked

to describe management.

Kroll concluded that ongoing losses due to the shrinking number of doctors would require Allied to continue to inject capital to keep the company afloat. Subsequent to Allied’s initial investment, results severely deteriorated and the number of doctors with the company declined from about one hundred at its peak to thirty-five in 2003. Kroll doubted APS generated profits. The company was in such bad shape that its bank lenders dumped its loans in June 2001 to Allied for about fifty cents on the dollar. TA Associates walked away. Despite purchasing the senior debt at a discount and equitizing some of the senior debt, Allied did not mark down its own junior debt investment in APS.

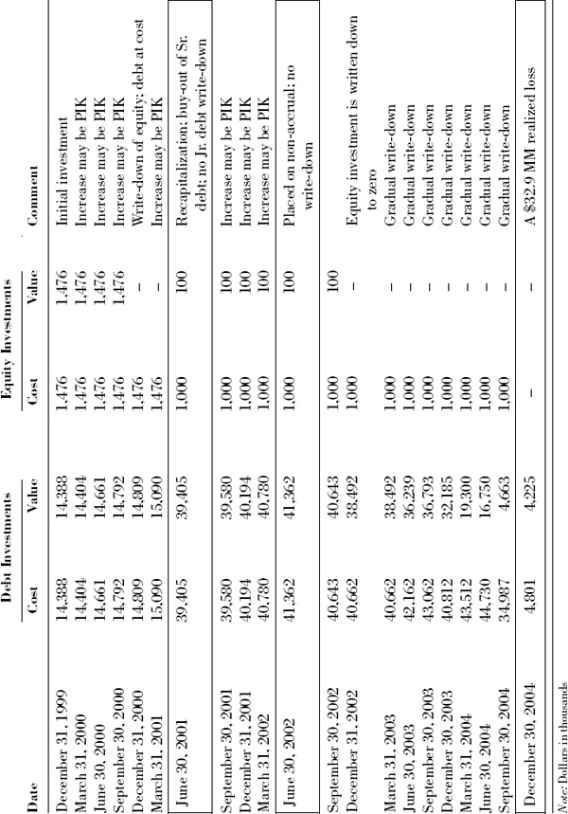

Instead, when Allied bought out the senior lenders, it took over APS and put Sweeney in charge. However, the business continued to crumble. Still, Allied carried its original loans to APS at full value on its books. It put the loan on “non-accrual” in April 2002, but didn’t begin to write-down the investment until December 2002, and then by only a small amount. Allied gradually wrote-down the value during 2003, before taking a large write-down in March 2004 just before APS went bankrupt. Allied had to take further write-downs through the balance of that year (see

Table 19.1

).

Table 19.1

American Physicians Services

In a September 2004

The Wall Street Journal

article, Allied claimed that it was optimistic about APS until late 2003, when APS lost a malpractice lawsuit and then received bad publicity after one of its patients died in early 2004. Kroll’s work showed that APS was in deep trouble long before that.

Kroll’s investigation of BLX was trickier. It turned out that Jock Ferguson, the investigator working on the project, knew Jim Carruthers, the partner at Eastbourne Capital who was doing a lot of digging into BLX on his own. As a result, the two crossed paths on several occasions. I instructed Kroll to cooperate with Carruthers but not reveal it was Greenlight that had retained the company. I was not interested in word getting into the market, the media, or to Allied that we hired Kroll—until Kroll completed its work. This led to several awkward conversations I had with Carruthers in which he informed me that someone hired Kroll and the Kroll investigator was quite experienced and was doing a great job. I sheepishly listened and encouraged Carruthers to share with Kroll, but to make sure it was a two-way street.

Carruthers developed several former BLX employees as sources. One of them gave him an internal August 2001 delinquency report that detailed $135 million of delinquent loans, or about 20 percent of the company’s portfolio. Allied had consistently said that BLX delinquencies were less than half this amount. Kroll used the delinquency report as a road map to the troubled loans. They talked to banks, brokers, former employees, and some of the borrowers.

In August 2003, Kroll completed a twenty-three-page report on BLX, with two binders of source document exhibits each six inches thick. Kroll found “a series of loans originated by BLX that appear to be frauds against the SBA.” Kroll wrote, “Further audits of BLX loans could uncover violations of SBA loan issuing rules and regulations and lead to the possible recovery by the SBA of many tens-of-millions of dollars from BLX.”

Kroll confirmed and documented BLX’s misconduct as the former employee who had contacted me had outlined and as Carruthers had discovered. BLX made loans that could never be repaid. Kroll found that in numerous cases BLX flouted many SBA underwriting requirements. The SBA provided the same type of lax governmental oversight that contributed to the savings-and-loan crisis in the 1980s.

What’s more, Kroll discovered that BLX issued new SBA loans to borrowers to pay off existing SBA loans, a clear violation of SBA eligibility rules. Kroll found cases where BLX did not confirm that borrowers made the required equity contributions; let borrowers take fees from loan proceeds; did not verify details in loan applications; and failed to properly assess a borrower’s credit history, capitalization adequacy, repayment ability and collateral. Kroll also found that BLX accepted inflated real estate appraisals. As SBA rules summarize, “The lender must analyze the borrower’s proposal as to whether it is a reasonable and appropriate undertaking for the business.” Kroll found that BLX violated this principle and many other more technical SBA underwriting requirements.

Kroll said that BLX focused on generating a high volume of new loans and said it heard indications that loan officers were not encouraged to be careful. BLX made its money based on loan volume and left most of the credit risk to U.S. taxpayers under the SBA program. This caused them to emphasize the quantity rather than quality of loans.

Kroll found that several borrowers received their loans and never even made a single payment. BLX relied on independent loan brokers to generate volume. Kroll reported that former BLX employees, who worked as loan underwriters, said that most loan approval decisions were based solely on the information in the loan application paperwork provided by the loan broker without verification.

Kroll found possible fraud in loans originated in Michigan, New York, South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia, where Matthew McGee, the convicted felon I discussed in Chapter 11, ran (and still runs) the Richmond office. Kroll said McGee was obviously overstepping SBA restrictions limiting his responsibilities after he was released from prison in 1997. Kroll said many of the loans out of the Richmond office defaulted.

When BLX hired McGee, the SBA approved the hire, provided that McGee not be involved in the financial affairs of the company or have credit approval responsibility. Kroll found that McGee routinely exceeded this authority by overseeing the acquisition, processing, and underwriting of all SBA loans in the Richmond office, often personally presenting them to the loan approval committee. Once approved, he would oversee the issuance of the new loans. Separately, the SEC had banned McGee from affiliating with an investment company. As Allied is an investment company, it appears that McGee violated his SEC ban because we have seen no evidence that Allied obtained an SEC waiver.

The fraudulent loans were pervasive and seemingly blatant. In one case in Georgia, BLX extended a $1.6 million SBA loan to Magnet Properties LLC, a motel company that operated a Howard Johnson Express Inn owned by Mangu Patel, who had already defaulted on another SBA loan in 1998. (Indeed, over the years, BLC/BLX would make several SBA-backed loans to Patel, many of which flouted agency lending rules and many of which defaulted. Kroll found that Patel himself often acted as the broker on some of these loans.) The new loan soon went into default, and BLX lost more than $1 million, three-fourths of which the SBA reimbursed on the taxpayer guarantee.

Kroll detailed problems with a number of other fraudulent motel loans in the South and a number of fraudulent gas station loans in Detroit and New York. Kroll found a motel loan where a month before the transaction the property had been “split,” separating the motel from the adjacent restaurant, administrative building and parking. BLX funded a loan based on the entire property, but had collateral for only the main motel. The owner put up a makeshift wooden fence to divide the property and sold the separated property free and clear.

In another example, BLX loaned $1.35 million in 2001 to Ryan Petro-Mart LLC, naming Amer Farran as the borrower and incorporated by Abdulla Al-Jufairi, a loan broker who brought many deals to BLX. We later learned that Abdulla Al-Jufairi (also spelled Al’Jufairi in some documents) and Pat Harrington, the head of the Detroit BLX office, were business partners. The tax assessment for the property was only $443,000, about $900,000 below the loan amount. Only one partial payment was made on the loan before it went into default a few months later.

BLX also made a $1.35 million loan to Farmington Petro-Mart, another Detroit-area gas station, and again listed Farran as the borrower. When interviewed by Carruthers, Farran said he knew nothing about the gas stations or the loans. He said he worked as an engineer at the Ford Motor Company. He implied that he was related to Al-Jufairi (we later learned he was a brother-in-law), who was listed as the contact person on this loan. “I guess I have a call to make to Abdulla, don’t I?” Farran said. The loan, of course, went into default.

Al-Jufairi was also listed as the incorporator of Golfside Petro-Mart LLC, which borrowed about $1.3 million from BLX, a loan that defaulted, as did a $1.35 million BLX loan to the Jefferson Fuel Mart. Al-Jufairi brokered that loan, and the records indicated it was a sham transaction between related parties at an inflated value financed by BLX. Also, $200,000 of the loan proceeds went to Hussein Chahrour, who pled guilty and received two years’ probation in a cigarette smuggling ring. He received a light sentence in exchange for testimony against other members of the ring, which used some of the smuggling proceeds to finance the Lebanese terrorist group, Hezbollah. Kroll said it was evident that the Detroit office of BLX barely reviewed the loan applications created by Al-Jufairi, again flouting SBA requirements. Including the Al-Jufairi loans, a total of eleven BLX gas station/convenience store loans in the Detroit area went into default for a combined $11.2 million.

In Norfolk, Virginia, Kroll found that BLX made a loan to the Town Point Motel, which the police closed just months later, claiming the motel was a center for the local drug trade. The owner of the motel stopped making loan payments and the city of Norfolk eventually tore it down.

Colleton Inns was a motel in Walterboro, South Carolina, where BLX held a junior loan. After it failed, a senior officer at Walterboro Bank (which held the senior loan) told Kroll, “I sold the motel on the courthouse steps for a little more than the total owing on the first mortgage. . . . BLX walked away with nothing, losing at least $1.1 million.”

Kroll found that since the beginning of 2000, there had been more than one hundred bankruptcy filings on loans issued by BLX. As with Al-Jufairi and Patel, Kroll found that delinquent borrowers often had ties to the independent loan brokers used by BLX. Sometimes the borrower and the broker were the

same person

. Some banks told Kroll that so many BLX loans went into default that the company earned a reputation of being the lender of last resort in the Preferred Lending Provider world.

BLX was pretty much getting away with this fraud, but occasionally regulators noticed. The early default of the $1.6 million loan to Magnet Properties LLC in Georgia triggered an audit in 2002 by the SBA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG), which found numerous lending violations (see

www.sba.gov/ig/2-35.pdf

). The SBA audit said that “the deficiencies in the subsequent loan application package of (Magnet) were concealed” and the loan did not meet agency eligibility criteria. The audit found that Patel paid himself $170,000 from the loan proceeds and used the loan to refinance the earlier SBA loan. This was a clear violation of SBA rules, which state, “No proceeds of a PLP [Preferred Lending Provider] loan may be used to either refinance or pay off an existing SBA loan.”