Forbidden Liaison: They lived and loved for the here and now

Read Forbidden Liaison: They lived and loved for the here and now Online

Authors: Patricia I. Smith

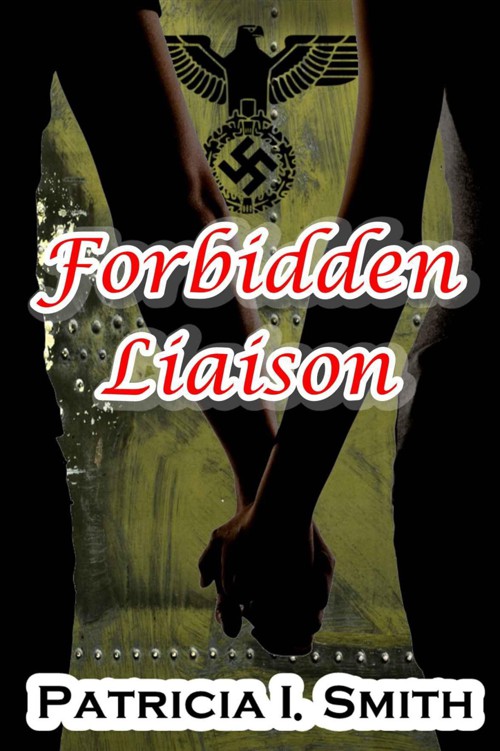

FORBIDDEN LIAISON

by Patricia I. Smith

Also by Patricia I. Smith

Tale of Two Women

To the Edge and Back

A Life Once Had

A New Beginning

Copyright 2014 Patricia I. Smith

First Kindle Edition

Published by Patricia I. Smith

Find the author at:

http://patriciaismith.wordpress.com/

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you are reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy.

All rights are reserved by the author, and no part of this book may be reproduced or, transmitted in any form by any persons without the permission of the author. Patricia I. Smith has asserted her right under the Copyright, Design and Patent Act of l988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

For my nephew Paul Watson: the bravest and nicest man one could meet.

Forbidden Liaison

They lived and loved for the here and now.

The Channel Islands, early October, 1943.

As he sat in the back of a black staff-car, Heinrich Beckmann knew he would have to deal with the memories and emotions of the past few years. He had seen too much, done too much: been wounded on the trek into Russia. Operation Barbarossa had been his nemesis. A bloodbath left in his wake. Now he thought killing was pointless: what did it achieve? A few metres of ground? A village? A town? Only to leave a trail of innocent dead civilians in the wash of the German Army on their way to conquer Moscow or Stalingrad. Perhaps now was the time to confront his demons. Did he have the courage to say, this is the man I want to become, not the man I have been forced to be.

‘This is it, Sir. Your billet,’ the young driver said as he pulled on the car’s handbrake.

Heinrich made no comment. He got out of the car, placed his bags on the pavement to look up at the drab, three storey building. Above the main entrance he noticed a small sign hanging from a rusty wrought-iron bracket. It was partly obliterated by the red and black German flag: the distorted shape of the black Swastika, encircled in white, swaying in the October breeze like a malevolent force about to stir itself. As the wind disturbed the flag he saw the sign in its entirety. It said BEACH HOTEL. But as Heinrich looked around, all he could see were more houses, more hotels: no beach: just brick walls and greying stucco.

He adjusted his cap, picked up his kit and walked to the front door. An air of inevitability swept over his head. It was a feeling he was familiar with. It had been with him for some time, like the dense smoke after an aerial bombardment, it would take time to go away. As his fist pounded against the green painted wood of the outer door, it was as if it was in competition with the click, click, of steel-tipped jackboots on tarmac as a group of soldiers marched down the road, the rhythm of their feet beating perfect time to their rousing marching song which was always the Horst Wessel. The expanse of grey uniform disappeared around the corner and Heinrich turned his attention to the door again and the brass letter-box, ringed with a powdery, whitish-green halo of dried brass polish. He became irritated when he was kept waiting longer than he thought was necessary.

It took some time for Margaret Wilfred to open the door to the unwelcome visitor. Her usual response would have been to give a smile and a friendly greeting to the holiday-makers who frequented the hotel. But for the past three years she had been forced to billet German troops, not the elderly or more affluent members of British society she and her husband had become accustomed to, so that blank stare remained on her face. Heinrich became impatient. Without invitation he walked straight in. Once inside he dropped his bags onto the hall floor. The weight of them shook the hall stand, rattling the umbrellas and walking sticks. The expression on Margaret’s face changed. Heinrich’s silence had unnerved her, but instead of lowering her gaze she stuck her hands into the large front pockets of her pinafore and continued to look at him. An animal would lie on its back baring its belly: a soldier would hoist a white flag. Ach, the woman, Heinrich thought. He had never been able to figure out the complexities of women, even though he had been married for seven years, and had two daughters.

‘Follow me,’ Margaret said, making it sound more like an order than a request, and as she showed Heinrich the door to her own private quarters, along with the troops communal kitchen, he instinctively studied the layout as he would the co-ordinates on a map. ‘The galley-kitchen is my own private domain,’ she said, not opening the door but pointing at it. It had originally been a laundry-room but she and her husband had it converted after

they

had arrived. ‘It is to give you people some privacy,’ she said. But Heinrich thought it had more to do with the fact she didn’t want to be seen mixing with the troops. Then she said, as Heinrich followed her up the staircase lugging his two heavy bags, ‘You must not walk through the house in muddy boots. Cleaning facilities are in the cellar and there is to be no alcohol or females in the rooms, and no noise after midnight.’

Heinrich listened, but didn’t appreciate the lecture. ‘It may be contrary to what you might think, but I did manage to keep a company of one hundred men in check on the battlefield. We are all house-trained. We do not piss in the sink, and we use the bath for the purpose it was intended,’ he said rather caustically. Margaret looked away. She wasn’t going to be intimidated by the German lieutenant. ‘You must also try and speak German,’ Heinrich reminded in his mother tongue, adding insult to injury. And as he stood examining the blankness on Margaret’s face, he repeated the sentence a second time. Still getting no response, he repeated it in English.

‘I am too old to learn foreign languages,’ came Margaret’s quick rebuff.

‘I can teach you,’ Heinrich replied, stressing the monosyllabic English words whilst at the same time trying to remember the correct grammar as well as the appropriate phrasing. He had taken an instant dislike to the woman, and began to wonder why he had been posted there. But he didn’t have to wonder about it for too long. ‘Who is the senior officer here?’ he asked.

‘I do believe you are,’ Margaret replied with an edge to her voice, and a smirk on her lips.

Heinrich could taste her dislike. ‘Then I think it should be I who decides what is to be done, and what is not to be done. Don’t you think, Mrs Wilfred?’ He was, by now, truly aggravated by the woman. ‘But I do happen to agree with you about the boots,’ he commented.

The room allocated to Heinrich was large and airy; luxury compared to what he’d been used to - a slit-trench on the Russian Front. No doubt he would still be spat at and cursed, but at least he wouldn’t be shot at on a daily basis. But he was getting to like that sudden rush of adrenaline when he knew he would have to stand and fight. Perhaps he could relax a little now, and not continually live on his nerves which gave him chronic indigestion.

‘I must congratulate you on keeping such an orderly house,’ he said as he looked around the room noticing how clean it was. His mother kept a clean, tidy home, and it was something he admired in a woman. In complete contrast, his wife was prone to bouts of laziness. He hadn’t known this when marrying her, but then he hadn’t known very much about her personal habits beforehand. His father had warned him of marrying in haste, and he also warned him about doing the right thing. And Heinrich had always done the right thing.

Margaret gave Heinrich a key and without offering any thanks for the compliment she turned and left.

The room Heinrich stood in was front facing with its own wash-hand basin, and the bay window almost stretched from floor to ceiling. Behind the door stood a wardrobe and a chest of drawers. Heinrich couldn’t resist running his fingers over the walnut veneer. Wood had a much warmer, friendlier feel than that of steel, and he touched it like he would a woman. But a woman would respond, give him some physical comfort. All the walnut veneer did was cast his mind back to his boyhood and remembrance of a past he thought he had forgotten.

As he opened one of the side sash-cord windows he stuck his head out into the cool, moist October air. He looked up and down the street. Nothing seemed to be moving now. If it was, it was moving so slowly it was hardly noticeable. He soon realised it would take him time to get used to this more leisurely pace, and so he turned his attention to the sea, which he could now glimpse over the rooftops of the houses opposite. As his eyes searched for a landmark, a gentle breeze blowing in from the ocean touched his face. It felt more like a woman’s caress than the harsh slap of the snow-winds he had become accustomed to as they blew in from the Steppes. The breeze somehow felt alien, though, he didn’t belong and he was experiencing a change; a change so dramatic that he couldn’t shuffle easily between the past and now.

Carefully putting his hat onto the bedside table, he unbuttoned his tunic and began to unpack, systematically putting away his belongings. Shirts always went in the top drawer, his underwear and socks directly underneath. The last items to come out of his bag were his hair brush; clothes brush, tooth brush, nail scissors and comb. Finally he pulled out a picture of his two small daughters which he placed in the centre of the chest of drawers. He hadn’t seen his children for almost a year and looking at the photograph he realised they would have grown so much he perhaps wouldn’t recognise them the next time he saw them.

Heinrich came from a large brood - two brothers and two sisters - and had always been reminded he was the baby of the family. As a boy if he didn’t keep his things under the bed or in his own allocated drawer space then they would have been lost in his elder brothers’ clothing which was often strewn about the bedroom floor.

His mother used to say, ‘Why can’t you be as tidy as little Heini?’ and Heinrich would stand grinning at his older siblings, who were almost men. But they would endlessly tease him when they got him on his own. ‘Always tidy, little Heini,’ was the chant they used to torment him with. ‘Mother’s favourite baby,’ they would add.

Heinrich knew he could always rely on his mother to protect him, and he often craved her presence just to tell him everything would be alright. Why was it the unconditional love of his mother and children he had never experienced with a woman, even his wife? This question had nagged at him for a long time, but he had never been able to reach any reasonable conclusion regarding its solution. He sighed, took out a cigarette and tapped it for longer than necessary on his left thumb nail. He put it into his mouth and lit it to then lie on his bed blowing smoke rings into the air. But when he found he had nowhere to put the ash he got up to look around the room for a suitable receptacle, but the cigarette deposits suddenly fell onto the floor and he quickly rubbed it in with the heel of his boot to try and stamp out all traces of the greyish substance. As there was nothing to put the stub in either – even the fireplace was boarded over, and the gas fire put in its place had been disconnected – he investigated the landing outside his door. Nothing: so he dropped the stub in the lavatory bowl in the bathroom and flushed it away before he went to investigate the rooms up in the attic.

Heinrich had noticed the patterned carpet when he first entered the hallway. It was predominantly red. Heinrich didn’t like the colour as it ran along the hallway, up the staircase, along the landing, then on up the other flight of stairs to the attic bedrooms. It reminded him too much of a battle field: the flecks of green and brown assimilating tufts of grass and the soil of the never-ending terrain that had stretched through Poland to the Russian border. Every so often, though, there was a little splash of yellow which reminded him of that familiar glare of dead men’s eyes as they appeared to follow him about. But the dominant swathes of red which, as they swirled, turned deep-crimson, reminding Heinrich of blood-stained soil. If he closed his eyes for only a moment the nightmares would begin and in order to stop the pictures of the Front taking over, he searched around for something to concentrate on. He found some respite fingering the grooves of barley-twist legs that held up an oblong-shaped hall table before he banged heavily on Margaret Wilfred’s door.