Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

History of the Second World War (10 page)

These difficulties set a narrow limit to the forces which the Soviet Union could move and maintain, except in a direct advance through the Karelian Isthmus against the strongly defended Mannerheim Line. This neck of land, seventy miles wide on the map, is much less in strategic reality. Half of it is barred by the broad Vuoksi River, while much of the remainder is covered by a series of lakes, with forests between them. Only near Summa is there room for deploying any considerable force.

Moreover, beyond the strategic difficulties of assembling any large forces on the apparently exposed parts of the Finnish frontier and pushing them deep into the enemy’s country, lay the tactical difficulty of overcoming the resistance of defenders who knew the ground and were able to exploit its advantages. Lakes and forests tend to shepherd an invading force into narrow channels of advance where it can be swept by machine-gun fire; they offer innumerable opportunities for concealed flanking manoeuvres as well as for guerrilla harassing. To penetrate into such a country in face of a skilful foe is hazardous enough in summer; it is much more difficult to attempt in the Arctic winter, when heavy columns are as clumsy as a man in clogs trying to grapple with an opponent in gym-shoes.

If Field-Marshal Mannerheim obviously took risks in keeping all his reserves in the extreme south until the Russians had shown their hand, his strategy was justified on the whole by the opportunities which the enemy’s initial penetrations offered to subsequent counterstrokes — especially in that kind of country under winter conditions.

As for the Russians, it is only to be expected that plans which have been based on a false assumption should break down when put to the test of reality. But that is not of itself proof of military inefficiency throughout the army concerned. While authoritarian regimes are particularly susceptible to the kind of reports on the situation which accord with their wishes, no type of government is immune from such risks. It is wise to remember that perhaps the greatest of all false assumptions in modern history were those on which the French plans in 1914 and 1940 were based.

PART III - THE SURGE 1940

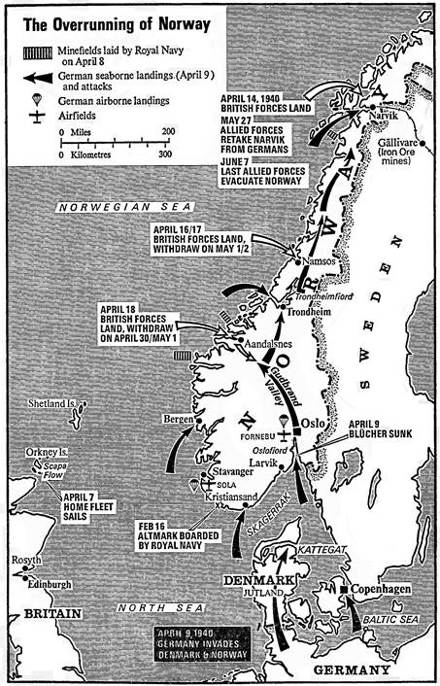

CHAPTER 6 - THE OVERRUNNING OF NORWAY

The six months’ deceptive lull that followed the conquest of Poland ended with a sudden thunderclap. It came, not where the storm-clouds centred, but on the Scandinavian fringe. The peaceful countries of Norway and Denmark were struck by a flash of Hitlerian lightning.

Newspapers on April 9 featured the news that on the previous day, British and French naval forces had entered Norwegian waters and laid minefields there — to block them to any ships trading with Germany. Congratulatory comment on this initiative was mingled with justificatory arguments for the breach of Norway’s neutrality. But the radio that morning put the newspapers out of date — for it carried the far more startling news that German forces were landing at a series of points along the coast of Norway, and had also entered Denmark.

The audacity of these German moves, in defiance of Britain’s superiority in seapower, staggered the Allied leaders. When the British Prime Minister, Mr Chamberlain, made a statement in the House of Commons that afternoon he said that there had been German landings up the west coast of Norway, at Bergen and Trondheim, as well as on the south coast, and added: ‘There have been some reports about a similar landing at Narvik, but I am very doubtful whether they are correct.’ To the British authorities it seemed incredible that Hitler could have ventured a landing so far north, and all the more incredible since they knew that their own naval forces were present on the scene in strength — to cover the mine-laying operations and other intended steps. They thought that ‘Narvik’ must be a misspelling of ‘Larvik’, a place on the south coast.

Before the end of the day, however, it became clear that the Germans had gained possession of the capital of Norway, Oslo, and all the main ports including Narvik. Every one of their simultaneous seaborne strokes had been successful.

The British Government’s quick disillusionment on this score was followed by a fresh illusion. Mr Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, told the House of Commons two days later:

In my view, which is shared by my skilled advisers, Herr Hitler has committed a grave strategic error . . . we have greatly gained by what has occurred in Scandinavia. . . . He has made a whole series of commitments upon the Norwegian coast for which he will now have to fight, if necessary, during the whole summer, against Powers possessing vastly superior naval forces and able to transport them to the scenes of action more easily than he can. I cannot see any counter-advantage which he has gained . . . I feel that we are greatly advantaged by . . . the strategic blunder into which our mortal enemy has been provoked.*

* Churchill: War Speeches, vol. I, pp. 169-70.

These fine words were not followed up by deeds to match. The British countermoves were slow, hesitant, and bungled. When it came to the point of action the Admiralty, despite its pre-war disdain for airpower, became extremely cautious and shrank from risking ships at the places where their intervention could have been decisive. The troop-moves were still feebler. Although forces were landed at several places with the aim of ejecting the German invader, they were all re-embarked in barely a fortnight, except from one foothold at Narvik — and that was abandoned a month later, following the main German offensive in the West.

The dream-castles raised by Churchill had come tumbling down. They had been built on a basic misconception of the situation, and of the changes in modern warfare — particularly the effect of airpower on seapower.

There had been more reality and significance in his closing words when, after depicting Norway as a trap for Hitler, he spoke of the German invasion as a step into which Hitler had ‘been provoked’. For the most startling of all post-war discoveries about the campaign has been the fact that Hitler, despite all his unscrupulousness, would have preferred to keep Norway neutral, and did not plan to invade her until he was provoked to do so by palpable signs that the Allies were planning a hostile move in that quarter.

It is fascinating to trace the sequence of events behind the scene on either side — though tragic and horrifying to see how violently offensive-minded statesmen tend to react on one another to produce explosions of destructive force, The first clear step on either side was on September 19, 1939, when Churchill (as his memoirs record) pressed on the British Cabinet the project of laying a minefield in Norwegian territorial waters’ and thus ‘stopping the Norwegian transportation of Swedish iron-ore from Narvik’ to Germany. He argued that such a step would be ‘of the highest importance in crippling the enemy’s war industry’, According to his subsequent note to the First Sea Lord: ‘The Cabinet, including the Foreign Secretary [Lord Halifax], appeared strongly favourable to this action.’

This is rather surprising to learn, and suggests that the Cabinet were inclined to favour the end without carefully considering the means — or where they might lead. A similar project had been discussed in 1918, but on that occasion, as is stated in the Official Naval History:

. . . the Commander-in-Chief [Lord Beatty] said it would be most repugnant to the officers and men in the Grand Fleet to steam in overwhelming strength into the waters of a small but high-spirited people and coerce them. If the Norwegians resisted, as they probably would, blood would be shed; this, said the Commander-in-Chief, ‘would constitute a crime as bad as any that the Germans had committed elsewhere.’

It is evident that the sailors were more scrupulous than the statesmen, or that the British Government was in a more reckless mood at the opening of war in 1939 than at the end of World War I.

The Foreign Office staff exerted a restraining influence, however, and made the Cabinet see the objections to violating Norway’s neutrality as proposed. Churchill mournfully records: ‘The Foreign Office arguments about neutrality were weighty, and I could not prevail. I continued . . . to press my point by every means and on all occasions.’* It became a subject of discussion in widening circles, and arguments in its favour were even canvassed in the Press. That was just the way to arouse German anxiety and countermeasures.

* Churchill:

The Second World War,

vol. I, p. 483.

On the German side the first point of any significance to be found in the captured records comes in early October, when the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, Admiral Raeder, expressed fears that the Norwegians might open their ports to the British and reported to Hitler on the strategic disadvantages that a British occupation might bring. He also suggested that it would be advantageous to the German submarine campaign ‘to obtain bases on the Norwegian coast — e.g. Trondheim — with the help of Russian pressure’.

But Hitler put the suggestion aside. His mind was focused on plans for an attack in the West, to compel France to make peace, and he did not want to be drawn into any extraneous operations or diversion of resources.

A fresh and much stronger incitement, to both sides, arose out of the Russian invasion of Finland at the end of November. Churchill saw in it a new possibility of striking at Germany’s flank under the cloak of aid to Finland: ‘I welcomed this new and favourable breeze as a means of achieving the major strategic advantage of cutting off the vital iron-ore supplies of Germany.’†

†

ibid,

p. 489.

In a note of December 16 he marshalled all his arguments for this step, which he described as ‘a major offensive operation’. He recognised that it was likely to drive the Germans to invade Scandinavia for, as he said: ‘If you fire at the enemy he will fire back.’ But he went on to assert ‘we have more to gain than to lose by a German attack upon Norway and Sweden’. (He omitted any consideration of what the Scandinavian peoples would suffer from having their countries thus turned into a battleground.)

Most of the Cabinet, however, still had qualms about violating Norway’s neutrality. Despite Churchill’s powerful pleading they refrained from sanctioning the immediate execution of his project. But they authorised the Chiefs of Staff to ‘plan for landing a force at Narvik’ — which was the terminus of the railway leading to the Gallivare ironfields in Sweden, and thence into Finland. While aid to Finland was the ostensible purpose of such an expedition, the underlying and major purpose would be the domination of the Swedish ironfields.

In the same month an important visitor came to Berlin from Norway. This was Vidkun Quisling, a former Minister of Defence, who was head of a small party of Nazi type that was strongly sympathetic to Germany. He saw Admiral Raeder on arrival, and impressed on him the danger that Britain would soon occupy Norway. He asked for money and underground help for his own plans of organising a coup to turn out the existing Norwegian Government. He said that a number of leading Norwegian officers were ready to back him — including, he alleged, Colonel Sundlo, the commander at Narvik. Once he had gained power he would invite the Germans in to protect Norway, and thus forestall a British entry.

Raeder persuaded Hitler to see Quisling personally, and they met on December 16 and 18. The record of their talk shows that Hitler said ‘he would prefer Norway, as well as the rest of Scandinavia, to remain completely neutral’, as he did not want to ‘enlarge the theatre of war’. But ‘if the enemy were preparing to spread the war he would take steps to guard himself against the threat’. Meantime Quisling was promised a subsidy and given an assurance that the problem of giving him military support would be studied.

Even so, the War Diary of the German Naval Staff shows that on January 13, a month later, they were still of the opinion that ‘the most favourable solution would be the maintenance of Norway’s neutrality’, although they were becoming anxious that ‘England intended to occupy Norway with the tacit agreement of the Norwegian Government’.

What was happening on the other side of the hill? On January 15 General Gamelin, the French Commander-in-Chief, addressed a note to Daladier, the Prime Minister, on the importance of opening a new theatre of war in Scandinavia. He also produced a plan for landing an Allied force at Petsamo, in the north of Finland, together with the precautionary ‘seizure of ports and airfields on the west coast of Norway’. The plan further envisaged the possibility of ‘extending the operation into Sweden and occupying the iron-ore mines at Gallivare’.

A broadcast by Churchill, who addressed the neutrals on their duty to join in the fight against Hitler, naturally fanned German fears.* There were all too many public hints of Allied action.

* On January 20 Mr Churchill, in a broadcast address, claimed success for the Allied navies at sea, and contrasted the losses of neutral ships to U-boat attack with the safety of Allied ships in convoy. Then, after a brief

tour d’horizon,

he asked: ‘But what would happen if all these neutral nations I have mentioned — and some others I have not mentioned — were with one spontaneous impulse to do their duty in accordance with the Covenant of the League, and were to stand together with the British and French Empires against aggression and wrong?’ (Churchill:

War Speeches,

vol. I, p. 137). The suggestion caused a stir, and the Belgian, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, and Swiss Presses hastened to reject it, while in London it was announced, with some reversion to the days of appeasement, that the broadcast only represented Churchill’s personal views.